Many Americans’ introduction to US history is the arrival of 102 passengers on the Mayflower in 1620. But a year earlier, 20 enslaved Africans were brought to the British colonies against their will.

As John Rolfe noted in a letter in 1619, “20 and odd negroes” were brought by a Dutch ship to the nascent British colonies, arriving at what is now Fort Hampton, then Point Comfort, in Virginia. Though enslaved Africans had been part of Portuguese, Spanish, French and British history across the Americas since the 16th century, the captives who landed in Virginia were probably the first slaves to arrive into what would become the United States 150 years later.

Four hundred years on, the captives’ arrival has informed nearly every major moment in American history, even if that history has been framed around anyone but Africans and African Americans.

“Historians, elected political figures [and] community leaders would prefer to sort of imagine the United States as a kind of mythic, Anglo-Saxon Christian place,” says Michael Guasco, an early American history professor at Davidson College.

In 1992, Toni Morrison told the Guardian: “In this country, American means white. Everybody else has to hyphenate.”

1619

After the first captives were forced on to Virginia’s shores by a Dutchman in 1619, the majority of the country remained white and relied mainly on the labor of Native American slaves and white European indentured servants. It was not until the end of the 17th century that the transatlantic slave trade made its impact on the American colonies.

1661

The first anti-miscegenation statute – prohibiting marriage between races – was written into law in Maryland in 1661, shortly after enslaved people were brought to the colonies. By the 1960s, 21 states, most of them in the south, still had those laws in place. Alabama was the last state to repeal the ban on interracial marriage, in 2000.

1776

The Declaration of Independence, which embraced in its first lines “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights”, did not extend that right to slaves, Africans or African Americans, with the final version scrapping a reference to the denunciation of slavery. Thomas Jefferson, a slaveowner himself, penned those lines rejecting slavery; he removed the reference after receiving criticism from a number of delegates who enslaved black people. This could represent “the fabric of the American political economy” ever since, some historians have said.

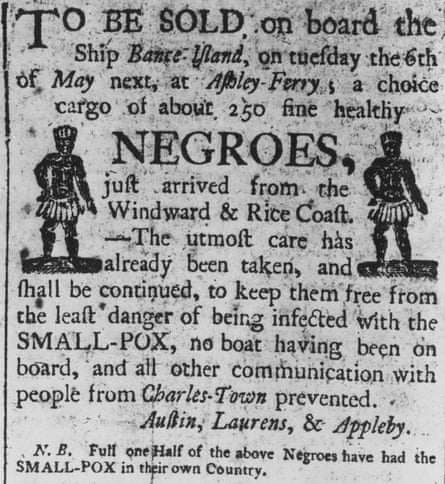

Slavery flourished initially in the tobacco fields of Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina. In the tobacco-producing areas of those states, slaves constituted more than 50% of the population by 1776. Slavery then spread to the rice plantations further south. In South Carolina, African Americans remained a majority into the 20th century, according to census data.

1860

The British-operated slave trade across the Atlantic was one of the biggest businesses of the 18th century. Approximately 600,000 of 10 million African slaves made their way into the American colonies before the slave trade – not slavery – was banned by Congress in 1808. By 1860, though, the US recorded nearly 4 million enslaved black people – 13% of the population – in the country as the American-born population grew.

Eight of the first 12 US presidents were slave owners. Proponents of slavery supported the efforts of groups like the American Colonization Society, who “sent back” tens of thousands of free black people – most of them American-born – to Liberia in the 19th century to prevent disruption caused by free descendants of slaves.

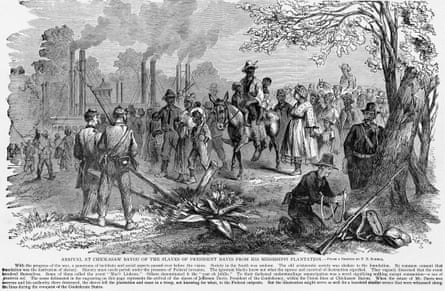

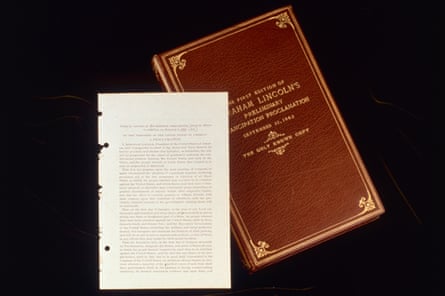

1865

According to Abraham Lincoln, the civil war was fought to keep America whole, and not for the abolition of slavery – at least initially. Southern states said they wanted to secede to protect states’ rights, but they were really fighting to keep people enslaved. Lincoln took on the fight for the freedom of slaves, some historians have suggested, because he was worried the British would support the south in its self-declared self-determination and recognize the south as a separate entity. If he had made the war about ending slavery, it would have looked bad for the south’s fight and the British supporting its cause. Lincoln’s death was probably the first casualty of “a long civil rights movement that is not yet over”, the historian Peter Kolchin has suggested.

1868

Some experts have argued that Reconstruction laid the foundation for “the organization of new segregated institutions, white supremacist ideologies, legal rationalizations, extra-legal violence and everyday racial terror” – further widening the racial divide among blacks and whites. Others have pointed out that the end of the war left black Americans free but their status “undetermined”, with the passing of “codes” to prevent black people from being truly free.

But eventually, under the 14th amendment, African American men were granted the right to vote. Also, African Americans were extended birthright citizenship: that extends to descendants of freed black slaves and immigrants to present day.

1898

The recession of the late 19th century hit the US. Knight riders went out in the dark, burning the homes of African Americans who bought their own land. They rode up to Washington to demand change as southern white Democrats rolled back many of the albeit limited freedoms from Reconstruction just a couple of decades before.

The Jim Crow era of segregation forbade African Americans from drinking from the same water fountains, eating at the same restaurants or attending the same schools as white Americans – all lasting until, and sometimes well past, the 1960s.

1926

As African Americans were shut out of jobs and opportunities during Jim Crow, and as more jobs became available in the north and midwest, more than 2 million southern African Americans migrated after the first world war. Still, even hundreds of miles away from southern segregation, these migrating Americans were met by “sundown towns”, where black people were not welcome after sunset, and by restrictions on where they could live in cities.

Oregon’s constitution, for example, only removed its exclusionary clause, prohibiting black people to enter the state, in 1926.

1954

In the lead-up to the end of Jim Crow and the civil rights era, the fight continued. For example: only in 1948 did the US military desegregate, by executive order. In 1954, in the Brown v Board of Education ruling, the supreme court ruled that segregation was unconstitutional and schools would have to integrate. Civil rights leaders led anti-segregation marches across the country in the 1960s. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law. Bussing African American children to white schools in white neighborhoods was deemed constitutional.

1965

“Slavery was gone but Jim Crow was alive. Almost all southern African Americans were shut out of the ballot box and the political power it could yield,” wrote Edward E Baptist in The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 attempted to correct this, prohibiting racial discrimination in voting and placing restrictions on a number of southern states if they tried to change voting rights laws. Those restrictions were recently overturned in a 2013 supreme court ruling.

Since the publication, in 2014, of The Case for Reparations, by Ta-Nehisi Coates, the subject of how to settle the financial debts of 250 years of slavery has risen up the political agenda. Those arguing for a financial settlement to descendants of slaves say it is designed to address the racial inequality that still lingers in the US.

A Pew study in 2017 showed that the median wealth of white households was $171,000 – 10 times that of black households ($17,100). The Democratic presidential hopeful Cory Booker has introduced a Senate bill on reparations and has been supported by Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders.

Meanwhile, voter suppression, another legacy of slavery and its aftermath, is also becoming a more visible issue. Aggressive attempts by mostly ex-Confederate states to limit the vote for poorer communities of color has become more pronounced since the gutting of the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

As Carole Anderson, academic and the author of One Person, No Vote wrote in the Guardian last week, about the 33 million Americans who have been purged from the voter rolls since 2014: “Not surprisingly, these massive removals are concentrated in precincts that tend to have higher minority populations and vote Democratic.”

This article drew on a number of books about the American history of slavery, including The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism by Edward E Baptist; American Slavery, 1619-1877 by Peter Kolchin; and Black Is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy by Nikil Pal Singh. It also used census data available online at census.gov.

This article was amended on 24 June 2021. A Pew study in 2017 showed that the median wealth of white households was $171,000, rather than the median income as an earlier version said. It was further amended on 25 February 2022 to add the 1860 enslaved population in Delaware and to reflect the correct Virginia borders in that year.