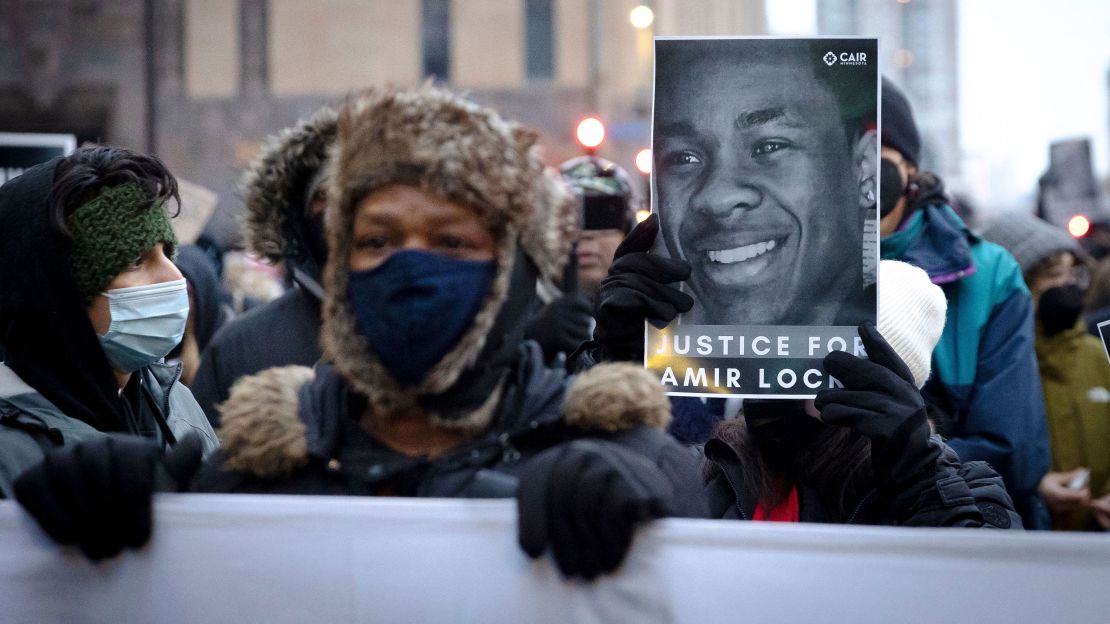

The shooting death of Amir Locke by a Minneapolis SWAT officer serving a no-knock warrant during a homicide investigation last week has prompted calls for an end to the practice of serving high-risk warrants on homes without giving occupants a chance to open the door.

There’s growing consensus among policing leaders that the risks of the tactic, which came into vogue during the height of the drug wars in the 1990s and into the 2000s, far outweigh any potential rewards.

“You have to go back years to understand why we have no knocks,” said Thor Eells, executive director of the National Tactical Officers Association. “They were developed as a tool, through courts, for the preservation of evidence … primarily crack cocaine. That’s no longer the case, and hasn’t been for at least ten years. (We)’ve been strongly teaching, advocating, for other alternatives.”

Other options taught are designed for officers to avoid the so-called ‘fatal funnel’ created by SWAT teams moving through a doorway to confront a potentially armed suspect – and most of those options have officers using time, distance, cover, and concealment to take custody of either evidence or a wanted person while lessening the risk of confrontation.

High-profile shootings by police officers over the last few years, the shooting of officers during execution of warrants, and the ubiquity of video footage showing just how risky and dangerous these raids are, have all contributed to police departments moving away from no-knock warrants.

Officers had warrants to search three apartments and arrest Locke’s cousin in connection with an early January homicide in St. Paul. When the execution of one of those warrants ended in Locke’s death, and police released video showing the speed at which the shooting unfolded, there were renewed calls for an end to no-knock warrant service in a city that announced an overhaul to the practice 14 months ago.

‘Just quit doing it’

The officer who shot Locke opened fire seconds after officers entered the apartment before 7 a.m., while saying “police” and “search warrant,” as Locke emerged from a couch wrapped in a blanket holding a handgun. Locke later died.

Police were pursuing evidence related to the St. Paul homicide, in which Locke’s cousin was a suspect. In the affidavit seeking the warrant, a sergeant detailed why police believed a no-knock warrant would be the best option: It “enables officers to execute the warrant more safely by allowing officers to make entry into the apartment without alerting the suspects inside. This will not only increase officer safety, but it will also decrease the risk for injuries to the suspects and other residents nearby.”

“A no-knock entry is necessary to prevent the loss, destruction, or removal of the objects of the search, or to protect the safety of the searchers or the public,” the sergeant wrote.

Peter Kraska, a researcher at Eastern Kentucky University who’s studied warrants and policing, said that no-knock warrants should be as difficult to obtain as they are dangerous to carry out. After Locke was shot, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey announced that Kraska would be advising the city on warrant policy.

“This (practice) has devolved into a mess once, it will again. Just stop. Just quit doing it,” Kraska said. “Put legislation in place that brings back the original intent of the Fourth Amendment – you’ve got to get a warrant, have to knock and announce, have to give proper notice, have to give time to answer the door, and if you need to engage in a risky arrest situation or volatile, dangerous arrest situation, figure out a different way to do it than to bust down a private resident’s door and manufacture a really dangerous situation.”

There’s not much data on warrants

The shooting of Locke renewed tensions between Minneapolis’ city council, which saw its oversight role diminished by voters last election, and the mayor. Voters in that city rejected a ballot measure to overhaul policing, drafted amid national fury over the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. The measure would have given the council oversight of a new Department of Public Safety and eliminated a requirement to employ a minimum number of police officers.

Before an officer shot Locke, Minneapolis garnered significant national media attention when city officials announced changes to its warrant policy during a nationwide reckoning over policing, prompted by Floyd’s murder and the fatal shooting of Breonna Taylor during warrant service in Louisville.

Some touted it as an accomplishment that Frey “banned” no-knock warrants. But the city did not ban no-knock warrants and, like most police department policies, its policy gives wide leeway to field supervisors to make decisions based on conditions they encounter and allows for no-knock warrants in certain situations. Under the new policy, warrants must be approved by the chief.

Frey acknowledged on Monday, at a city council meeting, that some of his claims about the extent of changes to warrant procedure weren’t accurate. Minneapolis police were requesting an average of 139 no-knock warrants each year, at the time city officials announced a change to their policy, according to a statement from Frey.

“What I will say, if you look at comparable cities that size, 140 no knocks would cause pause. I’d be looking at that saying, ‘Let’s go through these one by one,’ ” Eells said. “And I hate to say it. At the end of the day, I’m going to bet you … 140 no-knock warrants shouldn’t have been served as no-knock warrants.”

Eells said it’s better to think of no-knock warrants as a judicial waiver – giving police permission to not knock. Otherwise, warrants require officers knock, announce their presence, and wait a “reasonable” amount of time before forcing their way into a home.

But no-knock warrants have evolved into a tactic used by police, most commonly during the height of the drug war, and as police broadly saw the “violence of action” – booting down doors, moving quickly, sometimes with distraction devices like flash bangs, and getting more officers into a space quickly – as the most viable technique to gain compliance.

Though media attention often focuses on no-knock warrants after cases where officers are shot or shoot someone, they’re notoriously difficult to study, track and change.

Data on warrants is scarce. Judges aren’t always required to track or share warrant data across judicial districts, so it’s not clear how many warrants are approved or how often evidence from those warrants is excluded because of how the warrants were served. Courts are even more opaque than police departments. Police departments aren’t required to keep or share data on warrants either, though they’re often public records or made public after charges are filed. Most big-city departments track the performance of the SWAT, drug, and other units often involved in serving warrants, but there’s no clearinghouse for data.

Even where there’s agreement that change is necessary: Policing is a local effort, police culture can differ department-to-department but is broadly hesitant to change, and there are few national standards or requirements other than guidance set by courts when a tactic or procedure is challenged.

At least four states have banned no knocks

Legislating and overhauling warrant service is difficult because of the role search warrants play in criminal investigations and because of the various ways police serve warrants. Even a standard warrant can appear similar to no-knock warrants if officers only wait a couple seconds before forcing entry.

Kraska said it’s almost a “distinction without difference,” and that “the police have gotten used to – just like in Louisville but all over the country – showing up with a regular ‘knock and announce’ warrant, get to the door, and carry it out as if it were defacto no-knock raid.”

Even where no knocks are banned by law, police can still force entry during chases or if violence is imminent or in progress, and can still force entry on normal warrants after knocking-and-announcing, so banning no knocks won’t totally eliminate forced entry searches.

For these reasons, Kraska said, it’s more important to overhaul warrant service in general – including the types of investigations furthered by forced-entry warrants – than to just focus on no-knock warrants.

After Taylor’s death, the practice of forcing entry during warrant service was curtailed in Louisville, where police served just four warrants where officers forced entry during a 14-month period studied by the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting.

Kevin Davis, chief of the Fairfax County Police Department in Virginia, said it’s important to distinguish between forced entry during emergencies and warrants served during criminal investigations. He said that for the “furtherance of a criminal investigation – the recovery of evidence, recovery of property,” it’s better to avoid no-knock warrants altogether.

“I think there’s large scale agreement in policing that has resulted in better ways to execute search warrants,” Davis said.

At least four states – Florida, Oregon, Connecticut and Virginia – have banned the no-knock warrants, while other states have enacted laws that stop just short of doing so by only allowing them in certain circumstances. A host of others have enacted other changes, like requiring departments to keep data or officers serving warrants to use body-worn cameras.

“There’s a tendency to want to ban certain things,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum. “The real question should be, how do we look at these situations and ask what other alternatives could be used to achieve the outcome … how should training change and what alternatives should we be looking at to achieve a successful outcome? Those are questions situations like this raise.”

You’re going through a ‘fatal funnel’

Police departments, especially in big cities, are moving away from “violence of action” those units sometimes relied on, not just with warrants, but with use of force in general, because it shortens the time officers have to make decisions.

“When you think about it, making entry – announced or unannounced – is very high risk,” Eells said. “You’re going through a ‘fatal funnel,’ where the bad guy could fire rounds blindly at a doorway and have a chance of hitting us. If we don’t have to go through, we don’t want to. Who benefits from making an entry? The answer is the bad guy. So we’d say, that’s a tactically unsound decision.”

Police used to call the high-speed entry on drug warrants “hostage rescue on narcotics” because the tactics used during raids resembled how teams would enter a building looking for hostages. Kraska said early raid tactics were adopted from US military special forces.

“We’ve internally tried to exorcise that from an option that agencies are using,” Eells said.

Eells’ organization teaches a priority system – safety of hostages, victims or bystanders, law enforcement, and the suspect, in that order. In the last five years, they’ve added “evidence” to the bottom of the list, “meaning it gets the least amount of consideration.”

Many use-of-force training regimens teach officers to use time, distance, cover, and concealment to slow down volatile situations and lessen the likelihood of using force. Wexler said no knocks “are almost the antitheses of what we train now.”

Take a situation where the warrant is for evidence such as a handgun. “What’s the likelihood of us not making entry and it being disposed of? It’s not like the occupant has an incinerator. Where’s the gun going?” Eells said. “At the end of the day, if you’re going to risk human life, even including the suspect, because you want a piece of evidence … then it’s flawed analysis of risk mitigation.”

Internal politics also can play a role in how warrants are served, and by whom. A drug team may want to request a no-knock warrant to preserve the likelihood of getting the target in the room with sufficient evidence to further prosecution. And if the SWAT team says no, absent some command interaction, the narcotics team could serve the warrant on their own.

“You get people involved in spitting contests,” Eells said. “So what this boils down to – is law enforcement leadership. Having chiefs and deputy chiefs who are educated, knowledgeable, experienced enough in SWAT tactics, risk mitigation, decision making, selection, who are then providing effective leadership.”

Body cams show how perilous no knocks are

It’s long been known to people serving warrants how dangerous that can be, but now policymakers and the public both have access to a near-constant stream of video from body-worn cameras and other sources.

“And I think what body-worn cameras have done is underscored just how perilous these kind of situations can be,” Wexler said. “The reality is, this is how policing is changing. Police chiefs will look at that tape, analyze it, and will look at their own policy and say this is so high risk that they will be reluctant to authorize anything that isn’t the most narrow, compelling situation. It’s so much, so much risk involved. It’s just not worth it.”

Experts said there are at least three other options departments have in serving high-risk warrants. Officers could follow someone away from their home and attempt custody on the street, which Eells called a “take down away.” Another would be treating a warrant as if someone was barricaded in a home – surround it, contact the person inside, and ask them to come out. Or officers could open the door, and, instead of going in, announce their presence and give the person inside a chance to come out.

“All of which maximize safety for everybody involved,” Eells said.

Davis, who served on SWAT teams and is now chief of Fairfax police, said many departments have created internal approval processes that require more surveillance and planning before warrants are served. Better insight before the raid gives police other less-risky options for serving warrants.

“If it takes longer to do pre-raid surveillance to get a plan that meets scrutiny at the highest levels of the organization, that’s good. It wasn’t that long ago in policing that the execution of a search warrant, operationally, probably didn’t make its way past a lieutenant or captain’s rank,” he said.

Davis, who was commissioner of the Baltimore police department, said elected officials balked at the cost of body-worn cameras before Freddie Gray suffered fatal injuries in the back of a police vehicle. There was less concern over the cost after the crisis, he said. But if police are still going to serve high-risk warrants, the cost of surveillance or other tactics are worth avoiding potential crises, experts said.

“The challenge police chiefs have, across the country, is to articulate the necessity to do these things consistent with community expectations,” Davis said. “Does it cost money, of course … The cost of not is setting your city, your county, your town back a decade after a crisis occurs that people look at and decide something was preventable, and the right steps weren’t taken to prevent a crisis.”

CNN’s Kaanita Iyer contributed to this report.