The New Boomerang Kids Could Change American Views of Living at Home

Moving in with your parents is often seen as a mark of irresponsibility. The pandemic might show the country that it shouldn’t be.

Photography by Caroline Tompkins

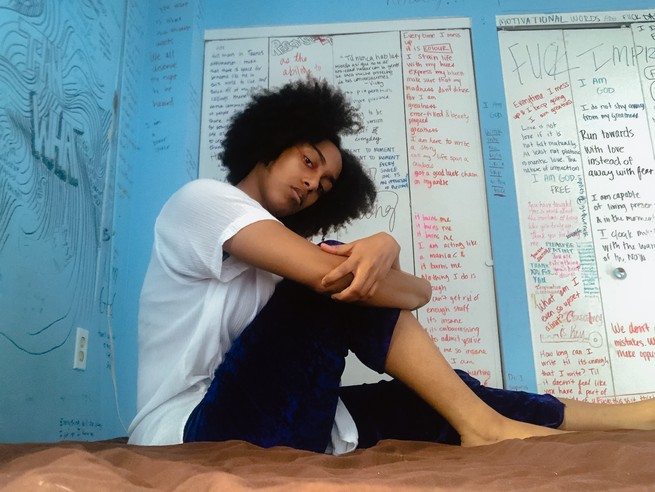

Image above: Marielle Brenner, age 25, in the living room of her parents’ house in Melville, New York, in June. She moved back in with them after the economic fallout from the pandemic made her rent in Chicago unaffordable.

For the most part, the pandemic has restricted motion in America. But one exception has been a large-scale nationwide reshuffling of humans between homes. Before the coronavirus came to the United States, many of the country’s young adults were working, studying, and building lives on their own. Now a great deal of them are back to living with their parents.

The number of American adults who have returned to living at home is enormous. A recent analysis of government data by the real-estate website Zillow indicated that about 2.9 million adults moved in with a parent or grandparent in March, April, and May, if college students were included; most of them were 25 or younger. Their sudden dispersal into their parents’ homes is, for some, the result of the suspension of spring classes on college campuses and, for others, the result of miserable economic conditions. A survey from the Pew Research Center in March found that the younger an American adult is, the more likely that the pandemic has deprived them or someone in their household of work or earnings. Rent and other expenses got harder to cover, or simply to justify, for a large group of young people, so they moved home.

In many segments of American society, living with one’s parents is seen as a mark of irresponsibility and laziness. The wave of young adults who have recently relocated is a symptom of a grave economic and public-health catastrophe, but living at home is not in and of itself a bad thing. In fact, one could even argue that it’s been unjustifiably stigmatized. Perhaps the pandemic is an occasion—an unwelcome one, sure—to reappraise a living arrangement that is often maligned, yet has become more and more common, in part because of how the past few decades have altered the arc of American adulthood.

The millions of young people living at home because of the pandemic may seem like the temporary by-product of highly abnormal circumstances, but in fact it is an acceleration of the norm. In 2014, living with one’s parents became the most common living arrangement for Americans ages 18 to 34, finally overtaking living with a romantic partner. By 2018, about 25 million young adults in that age range were living at home, per a Pew analysis of data from the Census Bureau.

The Great Recession contributed significantly to that figure’s steady rise. According to an Atlantic analysis of Census Bureau data, the number of 25-to-34-year-olds living with their parents increased by nearly 1 million from 2006 to 2010. This “boomerang generation” of young people returned home during that period for many reasons. The economic ones probably got the most attention: In the late aughts, a cohort of young workers was trying to make its way in a bleak labor market while collectively shouldering an exceptionally large amount of student debt. Of course they’d end up living somewhere that didn’t charge them rent.

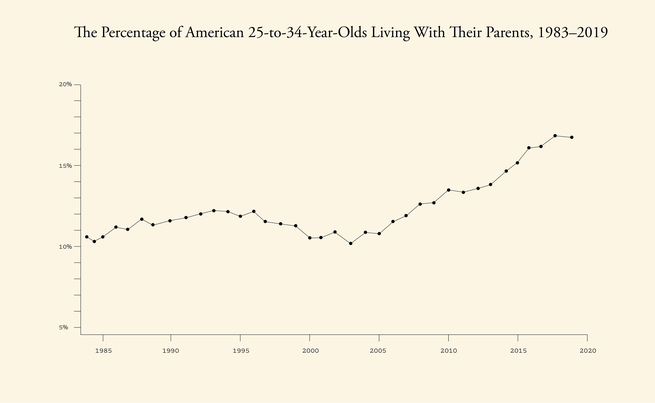

But focusing only on these explanations obscures a larger trend line. From the mid-1980s until the late 2000s, the share of 25-to-34-year-olds living at home hovered in the range of 10 to 12 percent, according to Census Bureau data. That figure did start to rise when the Great Recession began, but it continued to climb well after the recession was over. It hit 13 percent in 2010, 15 percent in 2015, and nearly 17 percent in 2018. At the end of the 2010s, roughly 2 million more Americans in the 25-to-34 age group were living with their parents than at the beginning of the decade.

That suggests that, independent of the Great Recession, something broader has changed in how people embark on their adult lives. “More people are in education longer, and people marry and have their first child later than ever,” Jeffrey Jensen Arnett, a psychology professor at Clark University, told me. “You put those two things together, and you have more people either remaining home or moving back home than was true 40 or 50 years ago.” Arnett came up with the label emerging adulthood for the open-ended developmental stage lasting roughly from age 18 to 29, and wrote a book of the same name.

The rising median age of marriage can be partly explained by the rise in nonmarital cohabitation among romantic partners, as well as by the fact that for many couples, marriage has become “a trophy”—a rite that marks the completion of the early stages of adulthood, rather than the beginning of them. Meanwhile, the widespread availability of birth control gives couples more agency in electing to postpone parenthood. These trends add up to a longer period in many young people’s lives when they aren’t living with a partner or children, and thus might continue living with their parents.

The second large-scale shift has to do with education—or really, with the way education prepares people for their working life. As the economy has tilted over the past several decades toward knowledge-based work, people with only a high-school degree have fewer pathways to financial stability. When this is the case, two things happen: Many young people spend more time in college or graduate school, and those who don’t pursue higher education can have trouble finding work that pays well enough for them to live independently. Both of these trends, Arnett said, steer more people back to their parents. But in general, those with a college degree are less likely to live at home than those without one, as are women, who tend to have more education and get married earlier than men; meanwhile, Black and Hispanic young adults are more likely to live at home than white ones.

Karen Fingerman, a human-development and family-sciences professor at the University of Texas at Austin, noted an additional factor that might be at play: As the share of parents who are married has declined, more solo parents might opt to live with their own parents, so they can have help raising their kids.

Meanwhile, another contributor to living at home doesn’t directly have to do with considerations like child care or education—some families simply prefer to have multiple generations under the same roof. “They co-reside because they want to,” Fingerman told me.

Those are the long-term forces that built up the large population of people living at home before the pandemic, and the pandemic has only added more (as well as, it should be noted, harming young people who no longer can afford rent, but don’t have parents who can take them in). The current surge in young people moving home, Arnett said, is likely to be the largest since the Great Depression.

In normal times, when people move in with their parents, their choice is typically planned out at least a little while in advance. But this spring, decisions about where to live were made “in the midst of a crisis,” Fingerman pointed out. “There was no thought—there was no, Gee, I want to live with my parents.” The decision to move back out probably won’t be made so quickly. The high up-front costs of moving into a new apartment alone or with roommates, Fingerman said, might encourage people to stay put even when the threat of the pandemic wanes, especially if the economy is slow to recover.

Public-health crises aside, the rise in the share of young people living at home in the past decade and a half has coincided with an important development in family life. “We were already shifting as a society toward stronger intergenerational bonds,” Fingerman said, pointing to research indicating that today’s young adults are in more frequent contact with their parents, and receive more guidance from them on emotional and financial matters compared with young adults several decades ago. In general, Fingerman said these strengthened connections represent a rewarding, welcome shift. They bring new closeness, though they can also bring up old tensions.

As young people have settled into their parents’ houses during the pandemic, one difficulty has been navigating a shared physical space. “One thing I’ve been dedicating some time to in quarantine is learning how to play the drums,” Fletcher Lowe, a 22-year-old new college graduate who recently moved back in with his family in Tulsa, Oklahoma, told me. “I bought an electronic drum kit a few weeks ago. I’m trying to be sensitive to the fact that I’m inhabiting a house. But the thing is, even with a plastic drum kit, it’s still going to make a lot of noise because you’re hitting it quite hard.”

In the course of reporting this article, I spoke with a 21-year-old in Colorado who has been sleeping on a futon in the living room of a two-bedroom apartment he shares with his mother and grandmother (“It’s cramped, to be honest”); a 21-year-old in Virginia who felt constricted by reverting to a twin-size bed (“It’s not sustainable”); and an 18-year-old in Missouri who was limiting his daily trips out of the basement for snack retrieval, so as not to disturb his parents while they made work calls near the kitchen (“I just have to be careful now when I go upstairs”).

Parents’ homes do have their charms, though. Eric Rivera, a 30-year-old in Brooklyn who moved in with his parents in New Jersey last weekend, has been looking forward to “weirdly enough, having a dishwasher and laundry—all these things that we don’t normally have in New York City.” Marielle Brenner, a 25-year-old who recently relocated from Chicago to her parents’ house on Long Island, is pleased to regain access to a backyard.

This mix of inconveniences and luxuries forms the physical backdrop for a bigger drama—the sometimes fraught, sometimes liberating renegotiations of parent-child relationships, now that the child isn’t actually a child anymore.

The pandemic has interrupted many young people’s sense of progress by forcing them to move home. During emerging adulthood, Arnett told me, young people lay the groundwork for the rest of their adult lives and generally aim to “get liftoff.” “The crisis throws a wrench into whatever you were doing, whether it’s work or school,” he said. “That’s got to be deflating.”

Before the pandemic, Chrissy Walker and her roommates in New York came up with a slogan for the year: “2020: Our year for sure.” This motto was intended to guide Walker, 22 years old and less than a year out of college, and her roommates as they scouted out new apartments, plotted career moves, and planned vacations during this exciting new post-college phase of their life. The slogan didn’t age well: Walker is now living at home with her parents in a suburb of Austin, Texas. “It just feels like you’re being jerked around, like you didn’t get a full start at things,” she told me.

Rivera, the 30-year-old who just moved back to New Jersey, is further along in adulthood, but had a similar feeling. His vision for the next few years was to continue advancing his career in tech-industry communications; move out of his shared apartment and get a place of his own; and “buy furniture that’s not from Wayfair—kind of these bigger steps that symbolize being more of an adult.” But he was laid off in March, which led him to leave that shared apartment and move in with his parents for at least the rest of the year.

A move home is an interruption for parents too. They’ve generally entered a phase in which, with their kids out of the house, “they get to turn back to their own lives after a 20-or-so-year hiatus,” Arnett said. Pandemic or not, having a child in the house again upsets their rhythms and impinges on their newly regained freedoms.

“Wherever we want to go, we go,” Peter Walker, Chrissy’s father, who’s 55, told me about what life was like after she went off to college. “We work as long as we want to work. We go vacationing without consideration about whether Chrissy would like it or not.” The pandemic has taken him out of a phase of life that was just as independent as the one his daughter was in.

Chrissy and her parents’ tastes and habits have occasionally collided since her move back home. For instance, Chrissy would often get hungry at night and, as she’d been doing regularly while living on her own, cook some food for herself at 10:30 or 11 p.m., which was a bother to her parents as they were going to bed. (In Peter’s telling, it was more like midnight.) “It became this huge thing, a giant tiff, for two days, about me [wanting to] eat after 10:30 and them wanting to go to bed,” Chrissy said. “The sentiment was like, ‘You’re our kid in our house; these are our rules,’ and it, to me, was like, ‘Well, I’m not a kid, and I didn’t really ask to be in your house right now.’”

There is a danger, Arnett said, that after a move back home, parents and children will lapse into their old roles. But at the same time, as adults, all parties have an opportunity to rewrite those roles. Indeed, the late-night-snacking conflict was resolved—Chrissy started eating earlier.

But some tensions are much less easily dealt with. Jordan, a 23-year-old recent college graduate in rural North Carolina, came out to their parents as nonbinary last year, and recently moved home after being unable to find work because of the pandemic. “My parents have come a long way in loving and supporting the LGBTQ+ community, but they still don’t use my pronouns all the time,” Jordan told me in an email. They said they were considering, “half as a joke but also half-serious,” putting up a poster on their bedroom door indicating their pronouns. (They asked that I not publish their last name, in order to avoid harassment.)

To some, the gaps between who they were when they left home and who they are now can feel unbridgeable. “I’ve used this time away from my family [to accept] my sexuality and political and philosophical beliefs, [most of which are different from theirs],” Tiara Primus, a recent graduate of Southern Oregon University, told me when I asked her near the end of her senior year about the prospect of moving back in with her parents. “Going back home would mean dumping all of that in a bag and hiding it in the closet.” (She’s currently living in a city not far from campus, in her friend’s mother’s home.)

Some of the regression to old family dynamics can be pleasurable, though. “I watch the news with my mom a lot,” Fletcher Lowe, the aspiring drummer, said. “That’s something I did in high school. It’s kind of nice, the little routines that are reentering my life that haven’t been there for a while.”

Indeed, living at home doesn’t seem to harm most parent-child relationships. A 2011 Pew survey of 25-to-34-year-olds who lived at home found that about half of them said doing so had no effect on their relationship with their parents; the remaining half was split almost evenly between those who said their relationships had gotten better and those who said their relationships had gotten worse.

In emerging adulthood, people “generally get along really well with their parents, much better than they did as adolescents,” Arnett said, referencing hundreds of interviews he’s done with 18-to-29-year-olds and their parents over the years. “The overwhelming consensus is, Man, we’re glad adolescence is over, because that was a contentious time.”

This opens up the possibility of wider-ranging conversations and deeper connection. Whereas teens are prone to hiding parts of themselves from their parents, Arnett said, emerging adults are usually more forthcoming. “It’s really gratifying to their parents, because parenting is a lot of work,” he told me. Parents’ attitude, in his experience is: “Now the payoff finally comes.”

“It’s been a blessing,” Peter Walker said of having his daughter back home. “We get to connect and chat whenever we’d like.”

Living at home also allows siblings to bond. “My sister was in sixth grade when I left for college, and now she’s entering 10th grade,” Lowe said. “There’s a lot of growing up that happens between those four years, so getting to see her being a real person is really cool.” When some young people move back home, they are also, like their parents, in the rewarding position of noting how their loved ones have matured.

Whatever their family relationships might be like, young people who have moved home can struggle with the symbolism of no longer living independently. “I was already clocking in for the obligatory mid-20s existential crisis right before the pandemic started,” Marielle Brenner told me. She is 25 and, until recently, was living in Chicago, working a job that didn’t inspire her or pay particularly well. She had student-loan debt and started cat-sitting to supplement her income.

Her parents—who live in Melville, New York—raised the possibility of her moving home. “I was very resistant to that, just because of the idea that’s been ingrained in so many young Millennials that moving home with your parents is a step back,” she told me. “It’s the ideal to be self-sufficient and live on your own, have your own place, have a successful job.”

When the pandemic forced many businesses to close this spring, Brenner’s roommate lost his source of income and had to move out. Unable to afford the rent on her own, she reluctantly concluded that returning to Melville made the most sense financially. “I never imagined living at home as a 25-year-old,” she told me the day after she moved in. “That sentence just feels like a failure.” Many of the other young adults I’ve interviewed recently feel the same way about moving back in with their parents, even though they recognize that the circumstances that led them to do it were entirely beyond their control.

This feeling of failure is hard to shake, because it’s the product of cultural programming. According to 2015 data from the Census Bureau, some 82 percent of American adults think that moving out of one’s parents’ house is a “somewhat,” “quite,” or “extremely” important component of entering adulthood. The median age that survey respondents identified for reaching this turning point was 21, and yet less than half of 21-year-olds had actually reached it.

Young people who don’t reach this milestone “on time” are often stigmatized. In 2005, Time magazine ran a feature about “young adults who live off their parents, bounce from job to job and hop from mate to mate,” and put on its cover a picture of a young man in business-casual attire sitting in a child-size sandbox. “What are they waiting for? Who are these permanent adolescents, these twentysomething Peter Pans?” the story inside asked. “And why can’t they grow up?” The article proposed a nickname for this generation whose exceeding clunkiness thankfully kept it from sticking around: “Twixters,” so named for the state of being “betwixt and between.”

This impatient tone is common in coverage of those inhabiting a life stage that was produced by titanic economic and cultural shifts that they had no say over. “Is Gen Y’s Live-At-Home Lifestyle Killing the Housing Market?” wondered one Forbes headline a few years after the Great Recession. CNBC was more forceful in 2017, with “Millennials Need to Move Out and Get a Life!” Meanwhile, the newspaper articles that over the years have offered advice to parents whose kids continue to live at home read at times like pest-removal guides.

This stance gives the mistaken impression that young people are content to essentially mooch off of their parents when they live together. “They’re helping with money and other kinds of care, like child care and food and cleaning,” Malcolm Harris, the author of Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials, told me, in defense of young people’s household contributions. “The stereotype of the basement kid is absurd and has very little to do with reality.” Indeed, Pew data from 2011 found that three-quarters of 18-to-34-year-olds living at home pitched in on bills for groceries or utilities. And as my colleague Derek Thompson has written, Millennials trail other generations in buying houses and cars less because young people don’t want them than because they’ve become unaffordable.

In many places around the world, living at home doesn’t carry some of the associations it does in the U.S. Fingerman, the UT Austin professor, brought up the examples of Spain and Italy, which have high rates of adults living at home; in Italy, for instance, 66.5 percent of 25-to-29-year-olds were living with their parents in 2018. She said this may be related to the availability of housing in those countries, but it is also related to cultural values. “They find the arrangement rewarding, they enjoy one another, and it’s part of their family life,” she said.

Plenty of people living in the U.S. find the arrangement rewarding too. Moréna Espiritual, an artist and an educator in New York City who uses they/them pronouns and is in their 20s, has been living with their mother and, on and off, their grandmother since before the pandemic. Separately, Espiritual’s 33-year-old sister is married with two kids, and their 30-year-old brother has a partner; all of those relatives share a home. “My family is very focused on staying together to support each other,” Espiritual told me.

Espiritual feels like living with family expands their world rather than limiting it. “I can still party; I can still have [meaningful] conversations” with peers, they said, “but I’ll come back to my home, where also I have the perspective of people that are older than me.”

Their household and others like it expose the problems with the narrative that living at home is a failure. “For me, specifically, and my family, being Dominican, and coming from a household of mostly Black and Indigenous people, the way we’ve been raised to relate to each other is more interdependent and communal, especially when most of your family are immigrants that arrive here and aren’t very aware of how to navigate American society,” Espiritual said. “People just learn how to establish and respect each other’s boundaries as they age, instead of moving away from each other.” This philosophy of family life, Espiritual told me, is common among their friends in Puerto Rico as well as the Dominican Republic and Colombia, many of whom are in their 20s and live at home.

Espiritual thinks that many people confuse living independently with being mature. “What does being grown mean? Does living by yourself mean that you’re grown?” they said. “Because I think I’ve learned how to better establish boundaries and communicate while living at home than some people who don’t.”

The conventional story about young people living at home misses that point. One could argue, as Espiritual effectively does, that the virtues of living at home have been swallowed up by popular middle-class American narratives about self-sufficiency and achievement. Discussions of young adults who live with their parents often focus on when they will leave, and what awaits them when they do, rather than what they can gain from life at home while there.

Besides, the stigma associated with living at home is more grounded in the past than the present. “Many people still hold the old normative expectations—you’re ‘supposed to’ become an adult by the time you’re 21 or 22—and haven’t adjusted to the new reality,” Arnett said. “I think parents and grandparents often look at today’s emerging adults and think, Now, at their age I was doing X, Y, and Z, and they seem to be nowhere near doing those things. What’s wrong with them? They are rather egocentrically applying the norms of their youth to today, when those aren’t the norms anymore.” Today’s young people are coming of age in a new era but still being judged by the standards of a previous one. The economic system that has led so many of them to move home in the past 15 years may well deserve criticism, but their response to it is rational.

In the 21st century, a better way to think about living at home, Arnett told me, is that it is in many cases involuntary but rarely stunting. Since Arnett started studying this life stage nearly 30 years ago, he’s seen the stigma around living at home weaken. One cause of this shift, he thinks, is the immigration patterns of the past few decades. In interviewing the families of young adults, Arnett has noticed that many immigrants from Asia, Africa, and Latin America are accustomed to different norms around living at home, and thus hold a more positive view of it. For some parents, he told me, “It’s more of a worry … if their kids move out in their 20s: Don’t they like their parents? Why are they moving into an apartment half a mile away? What’s wrong with that household?”

Another reason is simply that, as living at home becomes more common, people adjust to it. “It becomes more normal,” he said. “We shrug and get used to it.”

In fact, the pandemic might produce even more shrugging, and further update notions of what living at home symbolizes. “There’s a thing that we sometimes call ‘cultural lag’—society begins to change, but our cultural beliefs take a little longer to catch up,” Fingerman told me. “I think that was happening already, but with this big increase in the number of young adults who are going to be residing with their parents, and with a very clear explanation for why that occurred, I think the culture will shift, and people will very much consider this a normal pattern now.” This change in attitude may well be helped along by the fact that this recent wave of people moving home was the result of a truly unforeseeable global catastrophe that affected even those with credentials for and careers in previously healthy industries.

Marielle Brenner told me about the moment this spring when she let go of her opposition to moving home. She was videochatting with two friends on the West Coast. “I don’t know why it didn’t click with me before, but they were like, ‘No one will blame you if you’re moving home right now with your parents,’” she said. “I guess it was them that made it okay for me to allow myself to consider that decision.”

That said, she wonders what people will think of living at home after the pandemic. “If and when things get back to some sort of normal and unemployment goes down,” she said, “I have the fear that I will continue to stay here and it will be perceived as lazy.”

She has good reason to fear that. Writing in April in The Atlantic, the sociologists Victor Tan Chen and Ofer Sharone predicted, based on their two decades of research on unemployed workers, that the initial phase of widespread “solidarity and compassion for the millions who have lost their jobs” because of the pandemic will be followed by a resurgence of “the old stigmas against unemployed workers … as memories of the initial crisis fade and people find new reasons to fault others for not pulling themselves up by their bootstraps.” Public attitudes toward people who moved home during the pandemic could follow the same pattern: sympathy now, judgment later. (Likewise, Arnett thinks that stereotypes about irresponsible young people are “remarkably sturdy.”)

But maybe, this time, people will really start to embrace the new timelines of emerging adulthood. “More than ever, there’s no reason to hurry into adult life and set artificial deadlines,” Arnett said. “The norms for when you get married, have children, become fully employed, are a lot more relaxed than they used to be. Now we can use that to our advantage and take some of the pressure off.” Maybe this unhurried and understanding mentality will be the one that guides the people currently living at home when, 20 or 30 years from now, their own children are the ones doing the same.