In a bold and ambitious collaboration, Apple and Google are developing a smartphone platform that tries to track the spread of the novel coronavirus at scale and at the same time preserve the privacy of iOS and Android users who opt in to it.

The cross-platform system will use the proximity capabilities built into Bluetooth Low Energy transmissions to track the physical contacts of participating phone users. If a user later tests positive for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, she can choose to enter the result into a health department-approved app. The app will then contact all other participating phone users who have recently come within six or so feet of her.

The system, which Google and Apple described here and here respectively, applies a technological approach to what’s known as contact tracing, or the practice of figuring out everyone an infected individual has recently been in contact with. A recently published study by a group of Oxford researchers suggested that the novel coronavirus is too infectious for contact tracing to work well using traditional methods. The researchers proposed using smartphones, since they’re nearly ubiquitous, don’t rely on faulty memories of people who have been infected, and can track a nearly unlimited number of contacts of other participating users.Mitigating the worst

But while mobile-based contact tracing may be more effective, it also poses a serious threat to individual privacy, since it opens the door to central databases that track the movements and social interactions of potentially millions, and possibly billions, of people. The platform Apple and Google are developing uses an innovative cryptographic scheme that aims to allow the contact tracing to work at scale without posing a risk to the privacy of those who opt in to the system.

Privacy advocates—with at least one notable exception—mostly gave the system a qualified approval, saying that while the scheme removed some of the most immediate threats, it may still be open to abuse.

“To their credit, Apple and Google have announced an approach that appears to mitigate the worst privacy and centralization risks, but there is still room for improvement,” Jennifer Granick, surveillance and cybersecurity counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union, wrote in a statement. “We will remain vigilant moving forward to make sure any contact tracing app remains voluntary and decentralized, and used only for public health purposes and only for the duration of this pandemic.”

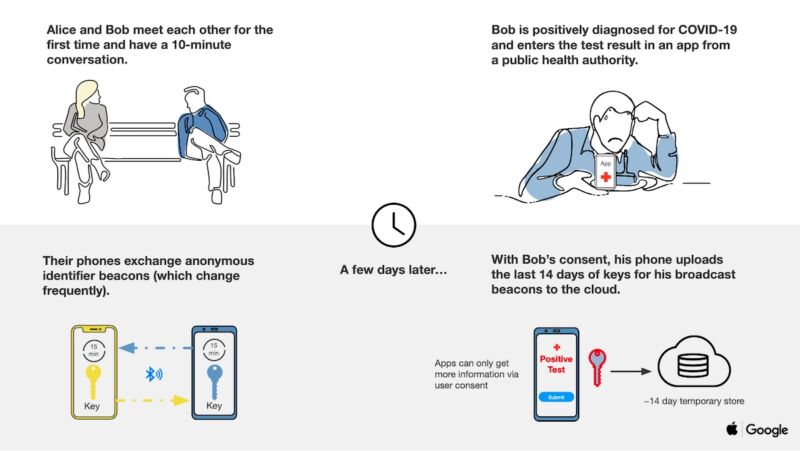

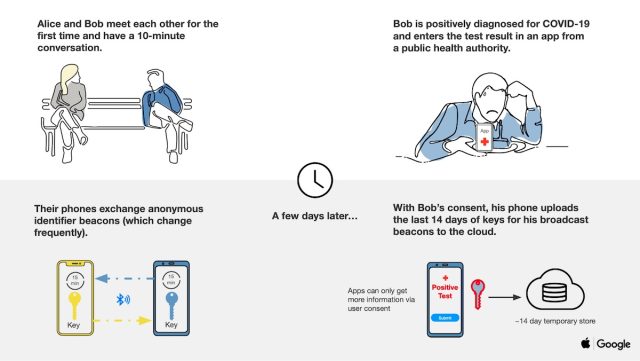

Unlike traditional contact tracing, the phone platform doesn’t collect names, locations, or other identifying information. Instead, when two or more users opting into the system come into physical contact, their phones use BLE to swap anonymous identifier beacons. The identifiers—which in technical jargon are known as rolling proximity identifiers—change roughly every 15 minutes to prevent wireless tracking of a device.

As the users move about and come into proximity with others, their phones continue to exchange these anonymous identifiers. Periodically, the users’ devices will also download broadcast beacon identifiers of anyone who has tested positive for COVID-19 and has been in the same local region.

In the event someone reports to the system that she has tested positive, her phone will contact a central server and upload 14 days of her identifiers. Non-infected users download daily tracing keys, and because of the way each rolling proximity identifier is generated, end-user phones can recreate them indexed by time from just the daily tracing key for each day. The following two slides help illustrate at a high level how the system works.

Apple and Google are providing other assurances, including:

- Explicit user consent required

- Doesn’t collect personally identifiable information or user location data

- List of people you’ve been in contact with never leaves your phone

- People who test positive are not identified to other users, Google, or Apple

- Will only be used for contact tracing by public health authorities for COVID-19 pandemic management

- Doesn’t matter if you have an Android phone or an iPhone—works across both

How it works (in theory)

Jon Callas, a cryptography expert and senior technology fellow at the ACLU, told me that the scheme is similar to the way raffle tickets work, with one party getting half of a paper ticket, the other party getting the other half, and—in theory at least—no one else being the wiser. When two phone users come into physical proximity, their BLE transmitters exchange tickets. Callas said that a similar COVID-19 tracking scheme known as the Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing appears to work roughly the same way.

“I keep a list of all the tickets I have,” he said. “If Alice tests positive, she releases her tickets and if ones that I have match, I know I had a contact with a positive person.” Callas went on to caution that ambiguities in the flow of both the Apple-Google platform and the Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing leave open the possibility of abuse because it’s not yet clear which parties get access to which tickets.

“If Alice releases the tickets she sent and the ones she received, she's outing the people who were near her,” he said.

Callas said he was involved in development of a third tracking scheme known as PACT, short for Private Automatic Contact Tracing. By contrast, he said, it has assurances that parties can only release sent tickets.

Begging to differ

Moxie Marlinspike, a hacker and developer who has both broken advanced crypto schemes and built them, was among the most vocal critics of the scheme as laid out. In a twitter thread that analyzed the way the APIs and cryptography interacted, he raised serious doubts about the plan.

"So first obvious caveat is that this is 'private' (or at least not worse than BTLE), *until* the moment you test positive," he wrote in one tweet. "At that point all of your BTLE mac addrs [BLE MAC addresses] over the previous period become linkable. Why do they change to begin with? Because tracking is already a problem."

So it takes BTLE privacy a ~step back. I don't see why all of the existing beacon tracking tech wouldn't incorporate this into their stacks.

At that point adtech (at minimum) probably knows who you are, where you've been, and that you are covid+.

— Moxie Marlinspike (@moxie) April 10, 2020

Marlinspike, who is the creator of the Signal encrypted messenger app and the CEO of the company that stewards it, said the next weakness is the amount of data that might have to be transmitted to user phones:

Second caveat is that it seems likely location data would have to be combined with what the device framework gives you.

Published keys are 16 bytes, one for each day. If moderate numbers of smartphone users are infected in any given week, that's 100s of MBs for all phones to DL

That seems untenable. So to be usable, published keys would likely need to be delivered in a more 'targeted' way, which probably means... location data.

That seems untenable. So to be usable, published keys would likely need to be delivered in a more 'targeted' way, which probably means... location data.

— Moxie Marlinspike (@moxie) April 10, 2020

Another possible weakness: trolls might frequent certain areas and then report a false infection, leading large numbers of people to think they may have been exposed. These kinds of malicious acts could be prevented by requiring test results to be digitally signed by a testing center, but details released on Friday didn't address these concerns. A variation of falsifying positive results is relaying BLE IDs collected from a hospital or other targeted area.

Technologist and privacy advocate Ashkan Soltani provided additional privacy critiques in this Twitter thread:

In my opinion - these types of data are poor proxies for the ground truth we really seek: actual #COVID19 infection rates -- which can only be truly known by widespread testing. If we had testing in place, it would make the need to pursue these privacy-invasive techniques moot

— ashkan soltani (@ashk4n) April 10, 2020

Soltani provided other useful details here and here.

Reading the specs

The cryptography behind the anonymous and ever-changing identifiers are laid out in this specification, which among other things assures that:

- The key schedule is fixed and defined by operating system components, preventing applications

from including static or predictable information that could be used for tracking. - A user’s Rolling Proximity Identifiers cannot be correlated without having the Daily Tracing Key. This

reduces the risk of privacy loss from advertising them. - A server operator implementing this protocol does not learn who users have been in proximity with

or users’ location unless it also has the unlikely capability to scan advertisements from users who

recently reported Diagnosis Keys. - Without the release of the Daily Tracing Keys, it is not computationally feasible for an attacker to

find a collision on a Rolling Proximity Identifier. This prevents a wide-range of replay and

impersonation attacks. - When reporting Diagnosis Keys, the correlation of Rolling Proximity Identifiers by others is limited to

24h periods due to the use of Daily Tracing Keys. The server must not retain metadata from clients

uploading Diagnosis Keys after including them into the aggregated list of Diagnosis Keys per day.

A separate Bluetooth specification, meanwhile, requires that:

- The Contact Tracing Bluetooth Specification does not require the user’s location; any use of location is completely optional to the schema. In any case, the user must provide their explicit consent in order for their location to be optionally used.

- Rolling Proximity Identifiers change on average every 15 minutes, making it unlikely that user location can be tracked via bluetooth over time.

- Proximity identifiers obtained from other devices are processed exclusively on device.

- Users decide whether to contribute to contact tracing.

- If diagnosed with COVID-19, users consent to sharing Diagnosis Keys with the server.

- Users have transparency into their participation in contact tracing.

Coming to a phone near you

Apple and Google plan to release iOS and Android programming interfaces in May. They will be available to public health authorities for developing apps running on one mobile operating system to work with apps running on the other. The official apps will then be available for download in Apple’s App Store and Google Play. Eventually, the companies plan to introduce tracing functionality directly into the OSes. Presumably, users can activate the functionality with a setting change.

Besides the privacy risks, there are other potential flaws. The system could cause undue alarm if it sends a warning that someone was exposed, when in fact the other party was dwelling in the same apartment building but in separate units. Bluetooth is also prone to a variety of flaws that can compromise its reliability and occasionally its security.

There are many important details that aren’t yet available and are crucial to understanding the privacy risks of the system Apple and Google are building. In normal times, it might be a given to advise people to opt out. Given the global health crisis presented by the ongoing pandemic, the call will be much harder to make this time around.

Post updated to correct the information uploaded from the phone of someone who tests positive.

reader comments

192