ILLUSTRATION: ANDREA BRUNTY, USA TODAY NETWORK, AND GETTY IMAGES

ILLUSTRATION: ANDREA BRUNTY, USA TODAY NETWORK, AND GETTY IMAGES

Dr. Robert Montgomery had several reasons for getting a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as he could.

As a transplant surgeon at a busy New York hospital, his patients were among the most vulnerable to the disease.

The pandemic has exacted a terrible toll on transplant recipients. About 20% of those infected died – more than 300 in New York City alone last year compared to just one or two transplant patient deaths in a typical flu season, Montgomery said.

He also is a transplant patient himself. The heart beating inside his 61-year-old chest is not the one he was born with.

So, Montgomery was doubly distressed when his body failed to mount a detectable response to his two-dose COVID-19 vaccine.

The medications that prevent rejection of a transplanted organ also block many transplant patients from making protective antibodies. A recent study from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine found that only 17% of transplant recipients had antibodies after their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, with an additional 35% responding after two shots.

Although COVID-19 vaccines work incredibly well for the vast majority of people, roughly 10 million Americans whose immune systems are compromised because of medication or disease may not be well protected.

"This isn't over for us," said Michele Nadeem-Baker, who has chronic lymphocytic leukemia that's out of remission. She got two shots of the Moderna vaccine in March and April, but is pretty sure she has no protection against COVID-19.

For Nadeem-Baker, a patient at Dana-Farber in Boston, the pandemic still looks a lot like it did during the worst of the outbreak: She always wears a mask, keeps her distances, avoids crowds.

"It isn't easy to continue living like this," she said.

Researchers are not yet sure exactly what an adequate immune response looks like – or what level of protection is enough. And once they figure out who is protected, they need to figure out what to do for people like Montgomery and Nadeem-Baker who aren't.

Montgomery's approach was to sign himself up for a clinical trial testing a third vaccine dose.

For him, it worked. After the third shot, testing as part of the trial showed that his immune system made both protective antibodies and longer-shielding T cells.

It's unclear how many of each is enough to safeguard someone against COVID-19, but Montgomery is satisfied he has at least some protection.

Not everyone can secure that peace of mind.

"Our patients are freaking out – and rightfully so," Montgomery said. "There's no good guidance out there."

Take precautions

Until results from clinical trials are in, Dr. Dorry Segev at Johns Hopkins Medical Center tells his transplant patients to "get vaccinated, act unvaccinated."

They should take all the precautions the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends for people with no protection, such as continuing to wear masks and socially distance, he said.

When the CDC last month abruptly lifted its mask recommendations for vaccinated people, Segev said, "the world quickly got less safe for immunosuppressed people." It's now far more frightening for transplant recipients to do something as simple as grocery shopping, because they don't know which unmasked person near them is actually safe.

Segev is studying the effectiveness of a third dose, hoping "there's something we will ultimately be able to do for transplant patients."

He hopes to soon launch a formal interventional trial, providing a third shot in a clinical setting, where he can ensure safety and track participants' response.

A handful of patients already have started getting extra shots – simply showing up at vaccination centers and not admitting that they've already been vaccinated. It would be far safer, Segev said, for them to get that third dose through a clinical trial. He is now looking for volunteers at transplantvaccine.org.

"It's really important for this to be out there so people know this is happening," he said.

Segev hoped that although transplant patients didn't develop antibodies, they might still have some protection against COVID-19.

Unfortunately, his and other hospitals are starting to admit transplant patients who contracted COVID-19 after being fully vaccinated. "That's almost unheard of in the general population," he said. "We're seeing this at a much higher rate in transplantation."

Segev, who recently examined 30 patients who'd had a third shot, said there were no safety issues except in one person who had a low-grade rejection event a week after the final dose. But that problem might have started before the shot. "We don't see a strong signal for it now," he said about possible rejection.

Segev also will look at whether transplant patients who failed to develop a response after two doses of mRNA vaccines – made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna – will fare any better after a booster. (His earlier research suggested that the single J&J vaccine was even less protective for transplant patients than the two-shot vaccines.)

Data can't come in fast enough for people who are worried vaccines may not keep them safe, Montgomery said.

"This is the No.1 problem in our field right now," he said.

Building a ‘wall of protection’

Luckily, most other immunocompromised people will get better protection than transplant patients, experts say.

Vaccines appear to be just as safe for them, and most seem to get at least some protection.

The problem is, it's impossible at this point to know how safe someone is. For the general population, which is more than 90% protected by the vaccines, there's no need to worry, experts said.

For people who are immunocompromised, there's no good way to tell if they're protected. Antibody tests, which look for some types of protective antibodies, may not tell the whole story and are only a snapshot in time, said Dr. Gil Melmed, who directs inflammatory bowel disease clinical research at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. The CDC has discouraged people from using the tests.

In everyone, antibodies are likely to decline over time, and it's not clear what level is protective.

Vaccines also generate T cells, often called the soldiers of the immune system, which seem to provide longer-term protection, but there are no commercially available tests to look for them.

To ensure they are safe, people who are immunocompromised should "build a wall of protection" around themselves, by getting vaccinated and making sure everyone around them also is vaccinated said Dr. Rajesh Gandhi, an infectious disease specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

"I don't think we're quite ready to throw caution to the wind," added Dr. Joshua Katz, a neurologist at the Tufts University School of Medicine, also in Boston. He recommends his patients continue to take precautions like masking, and ensuring that people around them are vaccinated.

Dr. Samir Parekh, a multiple myeloma specialist at The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai in New York, says immunocompromised patients should talk with their doctor about using accurate antibody testing to identify if they're at particular risk. "We are recommending testing for our myeloma patients who have immune suppression from their cancer as well as chemotherapy treatments," he said.

For patients with infammaroty bowel disease, vaccines appear to be safe and to provide about 80% protection, which is lower than for totally healthy people but still good, Melmed said.

He runs a registry tracking 1,800 inflammatory bowel disease patients to understand how they react to vaccination. He said it's too soon to know if IBD patients are getting more "breakthrough infections" after vaccination than the general population, but he hasn't seen worse outcomes among his registry members.

Melmed hopes the registry will help teach researchers vaccine protection wanes over time, and whether it fades faster in people, like his IBD patients, who are immunocompromised.

COVID-19 vaccine protection varies

Multiple sclerosis patients have been on a "roller coaster ride" for the past year, Katz said, with worries and fears about COVID-19. It turns out they are not an increased risk for catching COVID-19, he said, and vaccination poses no extra risk for someone with the disease.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society encourages everyone with MS to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

Whether vaccination is effective in MS patients seems to depend on which treatment they are on out of the 16-17 available, Katz said. Most people on the drug Mavenclad (cladribine), for instance, were well protected by COVID-19 vaccines, while only about 20% of those on Gilenya (fingolimod) and Ocrevus (ocrelizumab) made antibodies, he said.

Yet in a study of Ocrevus, even those who didn't make antibodies still made extra white blood cells after vaccination, suggesting they got some protection, he said.

For cancer patients, the amount of protection varies by cancer type and where they are in their treatment.

About 98% of people with solid tumors developed protective antibodies after vaccination, according to one study published this month in the journal Cancer Cell. By comparison, only 85% of blood cancer patients and about 70% of those on strong immune system therapies developed antibodies.

People should get vaccinated before starting chemotherapy if possible, said Dr. John Zaia, who directs the Center for Gene Therapy at City of Hope, which runs cancer centers in California. If that's not possible, they should delay vaccination until the end of their chemotherapy treatments to get the best response to the shots, he said.

Zaia is leading research into a COVID-19 vaccine developed at City of Hope specifically for cancer patients, using a platform designed for bone marrow transplant patients who lose protection from all vaccines during their transplant. Zaia said he has tested the vaccine so far in 60 healthy people and will next compare its effectiveness against the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

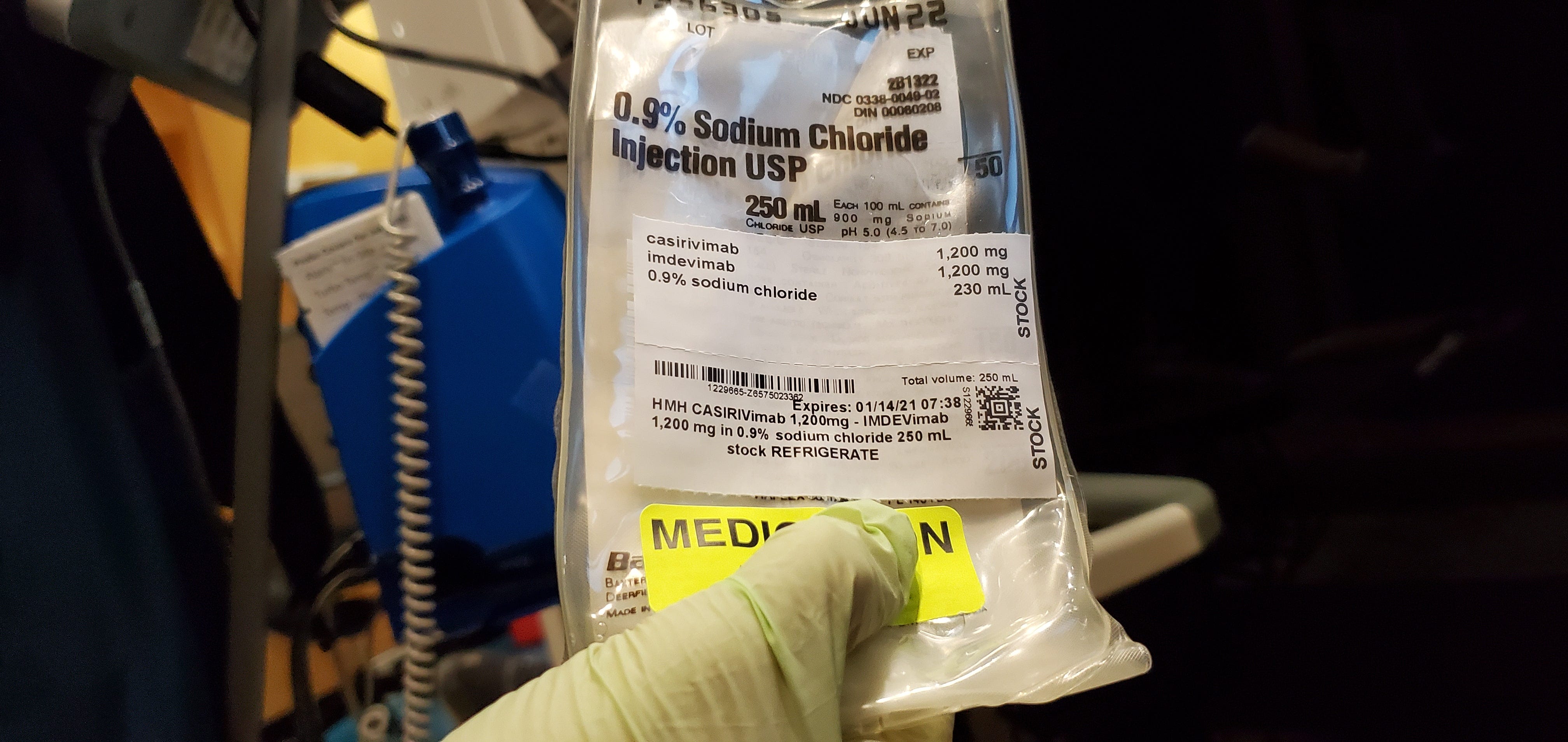

If cancer patients do catch COVID-19, they should consider getting monoclonal antibodies, drugs that help reduce the chances of a severe case of the disease, said Dr. Craig Bunnell, chief medical officer and a breast cancer specialist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

The same drugs may prove effective at preventing infection in people, like cancer patients, who can't get protection from vaccines, he added. Studies to confirm this are underway.

Living at high risk in a maskless world

Unfortunately, Nadeem-Baker belongs to the group with the least protection from vaccines and the highest risk for catching COVID-19.

The CDC's decision last month to lift the mask recommendation for those who had been vaccinated made her life worse. Even the unvaccinated took off their masks.

"Dropping the mask mandate heightened my sense of fear," said Nadeem-Baker, a former corporate communications executive-turned blood cancer patient advocate. She's particularly anxious about the variants, which seem to spread more quickly.

"I want to go back to living normally, just like everyone else," she said. "I feel like I'm outside of life looking in."

Her college-student son moved out to protect her. Her husband strips just inside the front door, putting all his clothes into a garbage bag to be washed. Her sister, who was widowed last year, is going into quarantine soon to pay her first visit. "I have not been able to hug her," she said.

The only things she feels comfortable doing, with her doctor's blessing, are taking nature walks or rides with her dog, and dining in the backyard with vaccinated friends.

Nadeem-Baker wishes strangers would be more understanding of those like her, who have to keep wearing a mask. "We're doing the best we can," she said. "I'm tired of explaining it."

She would consider joining a clinical trial to find out whether a third shot would be helpful for people like her.

"I hope something like that can help," she said. "I just want something that works."

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.