Where my mother grew up, in a traditional Sikh-Indian community in Manchester, it was a given she’d get an arranged marriage. The process kicked off when she was 19, when the area’s hottest matchmakers — elderly twin sisters — brought the first candidate, a misogynistic gynecologist, to her family home. They spoke in the kitchen, her mother pretending to wash dishes in the background and her brother hiding in a cupboard, eavesdropping. In the first few minutes, the gyno told her she’d be dropping her nursing career to look after his permanently bedridden mother, and my mom told him to get lost. Thus, the beginning of her matchmaking experience ended almost as soon as it began.

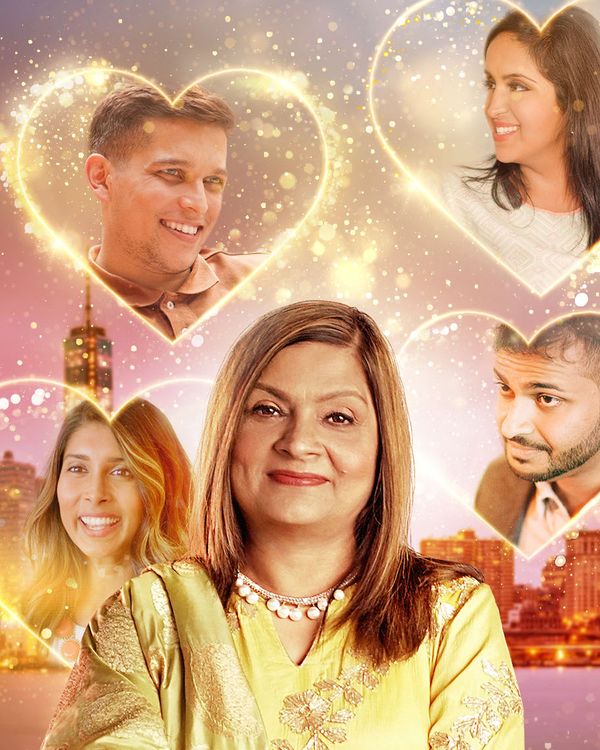

In other more conservative Indian families, my mom’s input wouldn’t have mattered; her attitude would have been suppressed, and she would’ve been hitched by the end of the week. This was over 30 years ago, and she said it was strange to see something that looked like her own experience on Indian Matchmaking, Netflix’s new reality-show-cum-docuseries about the Indian marriage machine. Executive produced by Smriti Mundhra, it follows Sima Taparia, a Mumbai-based matchmaker Mundhra met when her own mother solicited matchmaking services for her a decade ago. “There was pressure,” Mundhra told me over the phone earlier this week. “It was all cloaked in this idea of, ‘We want what’s best for you. We want you to be happy’ — but it was still pressure.”

Mundhra, who was raised in the U.S. and ultimately married outside of the matchmaking system, remained fascinated by arranged marriages and how the tradition was — and was not — adapting to a generation of Indians who had more education, money, and agency than their parents and grandparents but didn’t want to abandon their customs and family’s expectations. She made a documentary on the topic in 2017, A Suitable Girl, a broad and bitter portrait of traditional matchmaking in India. It follows three women up until their wedding days, documenting their loss of independence and observing the severe social and familial pressures they face throughout the process.

Its success landed Mundhra a meeting at Netflix, where she pitched Indian Matchmaking. The show follows Sima and six of her clients, all middle-and-upper-class Indian-Americans and Indians. Sima comes to them armed with stacks of “biodata” — a sort of Tinder-LinkedIn profile with a photo, bio, and lists of details like height and family background. She also asks the clients (and sometimes their families) what they’re looking for in a partner. Often, the factors include job stability, hobbies, and education, and sometimes it’s the qualities people might look for on an app or in a bar but won’t say out loud — are they good-looking, tall, in good shape? Other times, the criteria ventures into the openly discriminatory: Clients want someone fair-skinned or to be from a certain caste. Sima consults astrologists, to ensure horoscopes are compatible, and occasionally sends clients to “life counselors” and other matchmakers; her goal, in a long-established approach to Indian matchmaking, is to pair both couples and their families.

Since its release last Friday, Indian Matchmaking has stayed on Netflix’s top-ten most-viewed, but the backlash has also been swift and intense, and the bulk of it has come from people in the desi community. On the one hand, it’s been called cringey, which it is, but some feedback has been more deprecatory, with one desi woman describing the “full-body mortification” she had while watching it and questioning why “embarrassing/shameful” arranged marriages might be brought to television. Others said it simply confirmed what they already knew about the casteism, sexism, colorism, and classism of the process.

Shouldering this topic, in service of this audience, was never going to be easy. “We’re a billion and a half people around the world — there are so many different languages, communities, and religions — we couldn’t fit all of that into one show,” Mundhra says. What’s more, South Asians have had so little popular culture to address our experiences, let alone this specific one — the two that have entered Western discourse in the 21st century are the 2014 rom-com documentary Meet the Patels, about actor Ravi Patel’s experience being match-made, and Amazon’s Made in Heaven, a drama web series that follows two Delhi-based wedding planners. This is after decades of shows like The Bachelor and the formation of entire networks that are dedicated to the white experience of finding love.

Indian Matchmaking doesn’t offer a lot of context or even interrogate the kind of discriminatory criteria and attitudes that mark the matchmaking business Sima runs, which has unsettled some critics. Others have said the show endorses these practices without analyzing their complications, and many of its story lines do end with the implication that things between the couples will work out (none of them do).

There’s also the show’s failure to represent other, more sordid experiences: the demands for exorbitant dowries that accompany many traditional arranged marriages in India, and the often painful experiences of people, like my mother, who marry not only outside of the system but outside of their race. In India and its diaspora, abandoning this institution and its limited standards engenders everything from social outrage to violence.

But Indian Matchmaking wasn’t trying to argue for or against arranged marriage, or even interrogate its problems, and maybe that does feel like a missed opportunity. “I wanted a big, mainstream dating show for South Asian people,” explains Mundhra, “I wanted something South Asians could see themselves in,” and when it comes to the tradition of arranged marriage, Mundhra says she simply wanted to lay it all out, to “put it up for debate.”

Does Indian Matchmaking do that? I’m not sure that it does, and many of the desis and critics I’ve come across don’t seem to think so either. And as Nehmat Kaur notes in the Wire, some people, especially those who have had bad experiences with matchmaking, won’t even be able to stomach this show as a hate-watch: “It confronts us with our own loneliness, presents marriage as a solution and accomplishment, but then reveals the process of getting there to be an exercise in self-erasure — sorry, ‘compromise.’”

It is, however, an accurate portrayal of what someone like Sima does with clients like hers, and the kind of pressures this generation of Indian people may face when it comes to marriage. But this is all criticism that Mundhra welcomes, she says, recalling the problematic character of Apu, the Indian convenience-store owner she watched on The Simpsons growing up: “We didn’t think, Is it problematic? Who is it representing? We were grateful for it and got excited about it … We’re now at a point where we can actually hold representation to a higher standard and push for better and more nuanced stories. I want to be held accountable. Push me so I can push too.”

There have been a few recent productions — Never Have I Ever, Nora From Queens — that are groundbreaking simply because they are helmed by nonwhite creators that made something about their own lived experience. And the reckoning they’ve faced has been similar to the kind Indian Matchmaking is having right now: that these shows are reinforcing stereotypes, casting their subjects in a bad light, and failing to represent — or even misrepresenting — certain communities.

But much of the backlash isn’t criticism for the sake of criticism — it’s public opinion in action, it’s how the next thing gets better. For her part, my mother says she wished the show would have featured a more diverse cross section of Indian people, or what happens when things don’t work out between couples or their families, which has been the story with the current generation of our own family as it continues to practice arranged marriages. In spite of that, she’s still giddy over the fact that Indian Matchmaking exists and that people are watching and talking about it.

And I think it makes sense when people discourage others from watching shows like this one: Desis get scared when things like Indian Matchmaking come out because there isn’t anything else, and what if this is the thing people judge us by when they meet us? Because it doesn’t matter if Judd Apatow makes a bad movie about a white guy finding love, because he will always make another one. When it comes to something about the nonwhite experience, the stakes are higher — it has to be right, but it only will be if these shows and films keep getting made. “It’s a system, and it’s working as it should, and I’m happy about it,” says Mundhra, “That, to me, is progress.”