On a rainy spring morning in Muncie, Indiana, a White, middle-aged, conservative woman met a transgender woman for a date.

It did not start well. The transgender woman was waiting at a table when the other woman showed up. She stood up and extended her hand. The other woman refused to take it.

“I want you to know I’m a conservative Christian,” she said, still standing.

“I’m a liberal Christian,” the transgender woman replied. “Let’s talk.”

Their rendezvous was supposed to last about 30 minutes. But the conversation was so engrossing for both that it lasted an hour. It ended with the conservative woman rising from her seat to give the other woman a hug.

“Thank you,” she said. “This has been wonderful.”

This improbable meeting came courtesy of the Human Library, a nonprofit learning platform that allows people to borrow people instead of books. But not just any people. Every “human book” from this library represents a group that faces prejudice or stigmas because of their lifestyle, ethnicity, beliefs, or disability. A human book can be an alcoholic, for example, or a Muslim, or a homeless person, or someone who was sexually abused.

The Human Library stages in-person and online events where “difficult questions are expected, appreciated, and answered.” Organizers says they’re trying to encourage people to “unjudge” a book by its cover.

This setup leads to some of the most unlikely pairings anyone will ever see.

A feminist meets with a Muslim woman in a hijab and asks if she wears it by choice or compulsion.

A climate change activist meets with someone who thinks global warming is a hoax.

A Black antiracist activist meets with a supporter of former President Trump.

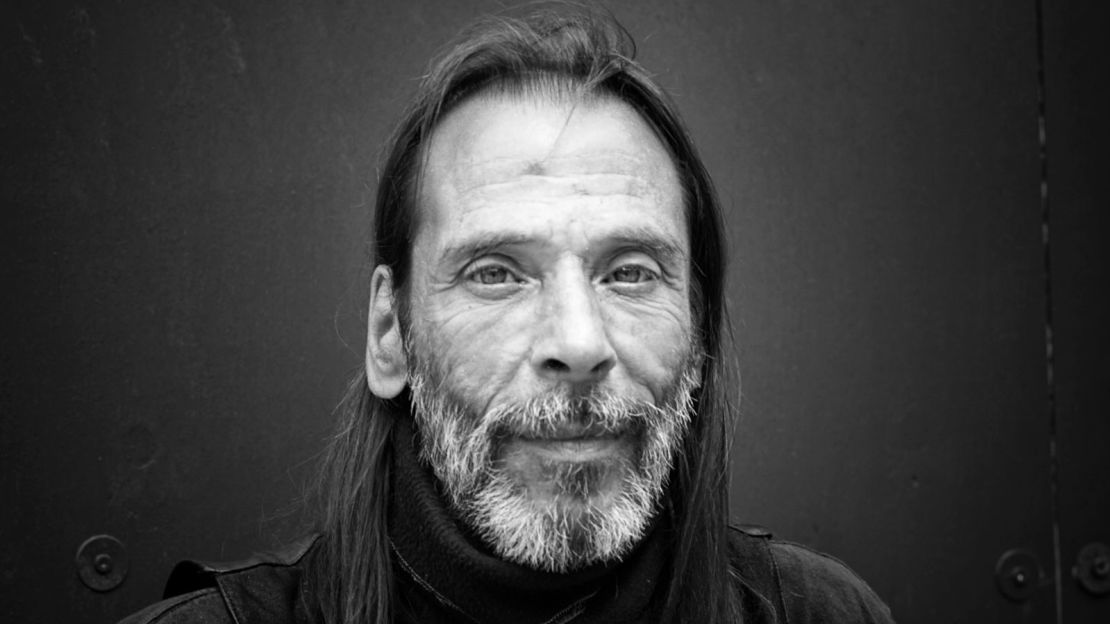

Or, in the case of Charlize Jamieson, a transgender woman meets a conservative Christian woman who thinks she is living in sin.

Jamieson says she agreed to be a “book” in the Human Library because she wants to encourage empathy. An animated and jovial conversationalist, she says she spent years denying who she was while working in corporate America.

“There’s rough edges around people, and people form opinions based on what other people say or what the TV news says,” she says. “And then you get in front of them, and you’re sometimes like a nail file, filing off those rough edges.”

This man founded the library to build bridges

The Human Library was created 21 years ago by Ronni Abergel, a Danish human rights activist and journalist who became interested in non-violence activism after a friend he describes as a “troubled youth” survived a stabbing in Copenhagen.

Abergel was born and raised in Denmark but lived in the US as an exchange student and has seen the political climate become increasingly partisan.

He wondered if a human library could bring people together like a traditional one. Only in this one, stigmatized or unconventional people would be treated like books – readers could loan them out, ask them questions, learn something they didn’t know and challenge their perceptions.

“I had a theory that it could work because the library is one of the few places in our community where everyone is welcome, whether you’re rich or poor, homeless or living in a castle, professor or illiterate,” he says. “It’s truly the most inclusive institution in our time.”

Abergel’s idea has spread like a bestseller. The Human Library has hosted events in more than 80 countries, in libraries, museums, festivals and schools. It has more than 1,000 human books in circulation in more than 50 languages, with an especially strong presence in American cities such as Chicago and San Francisco, Abergel says.

If people check out a book, they won’t need a translator. A librarian makes sure to pair readers with someone whose language they can understand.

“If you speak English, we make sure not to put you in a room with French books,” Abergel says.

Abergel believes the library’s mission has taken on more urgency in recent years. People across the globe are becoming more divided by social media bubbles, political beliefs and demagogues who cheer on these divisions to gain power.

How many people, for example, will tiptoe around holiday dinner conversations this year for fear of sparking a political argument with a relative? How many people will boycott holiday gatherings altogether because of who is hosting them?

Abergel says there’s a need for people to have conversations with others who see the world differently – minus the verbal combat.

“People want to have safe spaces to connect and maybe diffuse some of the tension in the air,” he says.

How to open a Human Library ‘book’

The Covid-19 pandemic has also reinforced the importance of the Human Library.

Most of its events were traditionally held in person, but organizers have adapted. The virus has driven millions of people indoors, isolated in their homes and fearful of being too close to strangers.

So on a recent afternoon, the library offered a virtual session that demonstrated how it can restore some of the human connections frayed by the pandemic.

The session opened when a cheerful host appeared on screen and introduced herself as the “head librarian.” Nestled in a brightly lit room lined with bookshelves, the librarian told the online audience of 43 “readers” that they could ask any question, “so long as you ask questions with respect.”

You will only have 30 minutes with each book, the host said, so make it count. “Don’t waste time asking about the weather,” she said. “Make it personal. Go deep quick.”

The screen briefly went blank, and then a broad-shouldered man with a trimmed beard and faded haircut appeared, sitting in what looked like a cozy bedroom. He was identified only as “Wheelchair User,” and he began by assuring listeners, “there is no such thing as a silly question.”

For the next 30 minutes, the others on the call fired questions: What was it like for you to go to school as a kid? How should I offer help to a person with a disability if I see them needing assistance in public? What do you do about sexual intimacy?

The man answered them all. He said being a wheelchair user is hard work. Taking a subway to see friends requires up to three hours of planning. Just making sure you’re near a bathroom that’s designed for a wheelchair user is a huge hassle, he said.

“Disabled people can’t be spontaneous,” he said. “I just can’t go for lunch today.”

Next up was a young woman, identified as “Eating Disorder.” She waved her long, slender hands expressively as she explained in wrenching detail how she dropped from 400 pounds to 100 pounds, triggered by an uncle’s cruel remark about her weight when she was a girl.

“It reinforced the idea that nothing is more important than being thin,” the woman said, her voice breaking with emotion.”

And so it went – person after person, opening the pages to some of the most intimate details of their lives. The session included about eight “books” in all, with titles ranging from autism, Black activist, transgender, ethnic minority and Muslim.

The emotional tenor of the conversations created an unexpected sense of closeness. Listeners nodded their heads in agreement or offered smiles of encouragement as the books flipped the pages of their lives.

Here was a case of the internet bringing people together, not driving them apart.

“It’s been lovely,” one human book said before signing off. “Stay safe and well wherever you are in the world.”

The conversations flowed with a professional smoothness, but much of that comes through training. Abergel, the Human Library founder, says books are vetted and trained to engage with others. He says that people who apply to become books but want to engage in political debates or have other agendas aren’t accepted.

“We’re completely neutral, as neutral as Switzerland,” he says. “As long as you’re not preaching hate or intolerance, you have potential on our bookshelf.”

The library helped bring together two neighbors

The nonpartisan nature of the Human Library has made it attractive to corporations interested in diversity training. The library has staged “reading hall” events where a company’s employees meet with books for 30-minute sessions at rotating tables. The library also has provided an internal “human bookshelf” for such companies as Microsoft, Heineken and Procter & Gamble.

There are now plans to create a Human Library app that would allow a reader to use a smartphone to search for a desired topic and set up a reading.

One of the library’s biggest supporters is Masco, a Michigan-based company that manufactures home improvement and building products. Keith Allman, Masco’s CEO, recalls a Human LIbrary conversation he had with a Muslim woman in a hijab, a head covering some Muslim women wear to show modesty in the presence of men outside their immediate family.

Allman says he was raised in a “lily-white, middle class background” on a farm in Western Michigan, so talking to her expanded his perspective.

“I’m raised Catholic, and I thought that (the hijab) was a control mechanism of men over women,” he says. “She had me thinking it’s not different than praying a rosary.”

Allman says his company partners with the Human Library because he doesn’t think it’s enough for companies to have employees from different races, genders and socio-economic backgrounds. Those employees must also feel like they’re being listened to, he says.

“The folks on the team don’t feel like they belong, or that their team member has their back, or that they can bring their whole self to work,” he says.

A Human Library session hit close to home for one Masco employee. Sue Sabo was talking to a Muslim book when she mentioned that she had a neighbor who was also Muslim, but she never asked her about her faith.

Maybe this is a good time to start, the book suggested.

So Sabo decided to do just that. She noticed her neighbor had some Islamic iconography on her front porch and asked what it represented. A conversation ensued. It was the first time Sabo had even talked to her neighbor about her faith. More conversations followed.

“Now she says wherever you have a question, please don’t hesitate,” Sabo says. “I can Google and learn a lot about the Muslim faith, but I can’t understand it as much as when I hear it from a person.”

After years of hiding her true self, she’s happy to answer questions

That personal interaction was what Jamieson, the transgender woman, sought when she decided to become a book at the Human Library.

Jamieson spent 30 years in retail and IT management, hiding who she was from the world. She had a wife and three children, but she thought she would lose everything if she came out as a woman.

That denial led to a dual existence, where she would dress in women’s clothes when nobody else was around. Once, she ordered pizza and forgot to change out of her dress when the deliveryman showed up.

“He didn’t even blink when I opened the door,” she says. “He’s probably seen it all.”

When Jamieson finally came out, she says her wife and kids supported her. When her son said, “I got your back,” Jamieson says, “it was like a thousand pounds came off my shoulder.”

She’s still married to her wife. And now, after years of hiding, she’s become an open book. She’s sharing her story with others, who may find their attitudes changed by the simple act of listening.

A conversation between someone like Jamieson and a stranger might not seem important.

But at a time when our political and cultural divisions have turned so hateful, listening to the story of a person with whom we disagree might be the most radical thing anyone can do.