Judith Arcana and her then-husband, Michael Pildes, were deeply asleep in their Chicago home when the phone rang around six o’clock one morning in the early 1970s. Pildes answered, and a woman on the other end asked for “Jane” — this was the code used by the Jane Collective, a clandestine network that helped around 11,000 women obtain illegal abortions in Chicago between 1969 and 1973. Arcana picked up the phone, and a panicked woman on the other end of the line told her that she was in the hospital across the street from where the couple lived. Suddenly, a man’s voice came through, saying, “We know where you are. We know who you are. We know what you’ve done.” Arcana and Pildes jumped out of bed, gathered all incriminating evidence from their home, and left in a hurry. The call turned out to be a false alarm — the man on the other end of the line was bluffing — but it was also an omen.

Arcana and six other women would be arrested in May 1972 and charged in connection with performing abortions, each facing a prison sentence of up to 110 years. “We were criminals,” Arcana tells filmmakers Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes in HBO’s The Janes. “We were felons.” The upcoming documentary, out on June 8, explores the complex and risky work the group undertook in order to help women who had nowhere else to turn: setting up a phone line to refer patients to doctors willing to perform an illegal procedure and, later, offering abortions themselves. As the likely fall of Roe looms just weeks away, The Janes pushes viewers to consider what lengths they would go to help someone get an abortion: Is it counseling that person? Connecting them with an underground network? Paying for them to travel to get the procedure in a state where it’s legal? Mailing them abortion pills? Learning how to perform a surgical abortion?

At the time the Jane Collective was operating, abortion was considered a felony homicide in Illinois; even sharing information about it was a crime. During this era, Cook County Hospital, one of the largest medical facilities in the city of Chicago, treated nearly 5,000 patients per year who tried to self-manage their abortion or went to an underground provider. Between 15 and 20 patients landed in the septic abortion ward every day, Dr. Allan Weiland, an OB/GYN who did his first clinical experience at Cook County, tells the filmmakers. Many of these patients were poor women and women of color; an unfathomable number of them became infertile or permanently scarred, and at least one patient died every month.

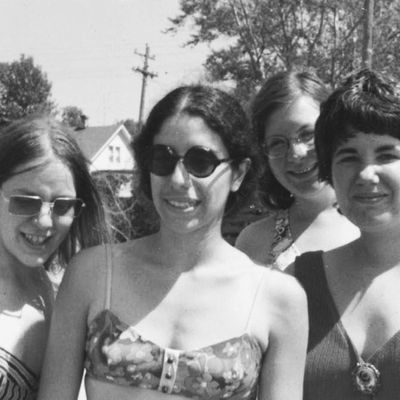

This desperate reality and the nascent feminist movement propelled a group of largely white, college-educated, and middle-class women to form the collective. In 1965, a student activist named Heather Booth helped a friend’s sister connect with a doctor to obtain an illegal abortion; when other desperate women heard about it, she suddenly found herself running a whisper network with like-minded volunteers. The effort eventually became Jane. Nearly 100 volunteers were involved with the effort in one capacity or another over the span of four years, though never at the same time. They were anonymous activists forged in the antiwar and civil-rights movements, students and teachers, mothers and housewives. Many had illegal abortions themselves and didn’t want other women to experience the same horrors.

Volunteers answered phones to counsel patients, drove them from “the front” where they waited to “the place” where the procedure was done, and watched over their children in the meantime. This work was possible due to the protections afforded by their privileges. The women of Jane offered their homes as safe houses in nice neighborhoods where police wouldn’t interfere and chauffeured patients through neighborhoods where no one batted an eye at white women. They knew attorneys who would rush to their side if they were arrested. And they had the means to handle any legal fallout. “Not only was I a nursing mother, I was a college graduate, a white woman married to a lawyer,” Arcana says in the documentary. “All of those things were going to get me low bail.” Chicago authorities allowed them to operate unimpeded until the May 1972 sting. The collective continued to provide abortions as the case moved through the court, and the charges were dropped when, seven months later, abortion became legal nationwide.

The cost of the illegal procedure Jane offered started at $500, or between $3,200 and $3,900 in today’s dollars. But the collective never denied care to a person who couldn’t pay for it (none are known to have died after receiving Jane’s care, either). The network predominantly served poor women and women of color — who still face the most obstacles in obtaining access to abortion care today — after New York legalized abortion in 1970. These abortion seekers “were very, very, very different from the women who were in Jane,” Laura Kaplan, one of the volunteers and author of The Story of Jane, says in the documentary. She adds that it felt complicated to provide abortion care to patients with life experiences that were so different from their own. “I was pretty ignorant of the class issues,” another volunteer admits. “I wonder how offensive we may have unintentionally been.” Now, women from marginalized communities, particularly Black and brown women, are on the front lines of the fight for reproductive justice in the most restrictive anti-abortion areas of the country. They know best the needs and challenges facing the communities they serve, so as legislation becomes increasingly punitive for patients, providers, and advocates, it’s imperative that those of us who want to help follow their leadership.

I now live in North Carolina, one of the five states in the nation with a pre-Roe abortion ban on the books. Whether it will be enforced after the expected Supreme Court decision remains murky. Knowing the future that awaits us after Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, I’ve asked myself many times what I would be willing to risk. I don’t know the answer yet. But Jane showed us what is possible when conviction triumphs over fear; as the nation turns the clock back half a century on women’s rights, I hear Booth telling the filmmakers, “Sometimes you need to stand up to illegitimate authorities, and sometimes there are unjust laws that need to be challenged.” To do so again is our moral imperative.