Susie Hamilton’s second annual Aspic Invitational was a shimmering sight to behold: paper thin cucumber slices dancing in a lemon conga line, olives marching in rows across a perfect terrine, shrimp cavorting in a ringed jelly sea.

Although it started as a fanciful add-on to a holiday party in her midcentury home in Windcrest, Texas, which has its own Instagram, Hamilton soon found she had struck a retro nerve. She and her husband Marc Sauceda share a love of vintage cars and clothes, and they wanted their open house to have a "time travel" aspect to match their architectural décor. It’s like immersive performance art, and she even laughs about having watched "The Dick Van Dyke Show" reruns to prepare. To her surprise, many attendees brought an entry, and it ended up being the highlight of the event. Her sister Morena Hockley is a professional crafter and the wife to an orthodontist, so her inaugural entry was particularly hilarious, although it was unflavored and not really meant to be eaten.

Then, after a pandemic hiatus, last year’s event ballooned, with so many entrants they ran out of table space. The growth in technical skills of her friends the second time around surprised her, and she says proudly that this time, "Almost all were edible!"

I have it on good authority that one of them consists entirely of congealed barbecue sauce, so I’ll just take the judges’ word on that.

The Aspic Invitational is one of the most spellbinding examples I’ve seen, but it’s just one in a quivering flood of social media and food blogger bits on gelled goodies. Hamilton notes that her own Instagram and friends’ posts got lots of responses, ranging from amused adoration to unmitigated horror — and that’s part of the fun. So, why are we so enamored of the jiggly stuff these days? What is it about this time and place, and why is it suddenly everywhere, sweet and savory, kitschy and sophisticated?

Preserving the past

As a somewhat perplexed devotee myself, I’ve been following gelatin and aspic-related conversations for a couple of years now, and I have some answers. There’s actual gastronomical appeal, but it’s inextricably intertwined with nostalgia — both what we remember from childhood, and what we long for from bygone eras. There’s also a pandemic-related interest in home cooking and a return to the safety of our family roots, even if they’re a little disturbing. I hope you’re sitting down, though, because the main common thread bouncing through all of these jellied elements? It’s art.

Art? Yes, and I'll get to that. But first, am I saying you should actually eat this stuff?

Well, I really can relate to gelatin’s continuing appeal, not just as a curiosity meant for ridicule, but as an actual food that is intended to be consumed. I grew up eating it at school and sometimes at home, and I confess I still enjoy it from time to time. I’m not alone, either. There are multiple social media groups dedicated to vintage recipes and filled with posts and comments about making Jell-O-based "salads," although they’re often thought of as a dessert these days. There’s a lot of laughter and comments like “Eww!” but many of us here in the U.S. still put on our ugly sweaters and make lemon-carrot salad, lime gelatin with cottage cheese and pears, and orange-nut cranberry molds every Thanksgiving or Christmas, even though we sometimes feel a little sheepish about it.

We shouldn’t feel ashamed, though. Gelatin shimmied into popularity around the turn of the 20th century as refrigeration became more common and mass production gained literal steam. Prior to its mass production, making a gelatin recipe required hours of boiling and multiple rounds of fine-straining to clarify it, making it largely the purview of the wealthy, going back to 1600s Europe. A relatively inexpensive box of powdered gelatin could yield a speedy and spectacular tower of fancy-looking food, shiny and stylish, using only thrifty bits of meats, vegetables and fruits, often all in the same dish. A person could express something of themselves through the decoration. Gelatin coatings helped preserve leftovers, too, in the days before plastic wrap and industrial food additives. As food goes, it’s uniquely utilitarian and egalitarian, part of the proud tradition of belief in the American Dream. That’s only part of the story, though.

Asia's jelly authority

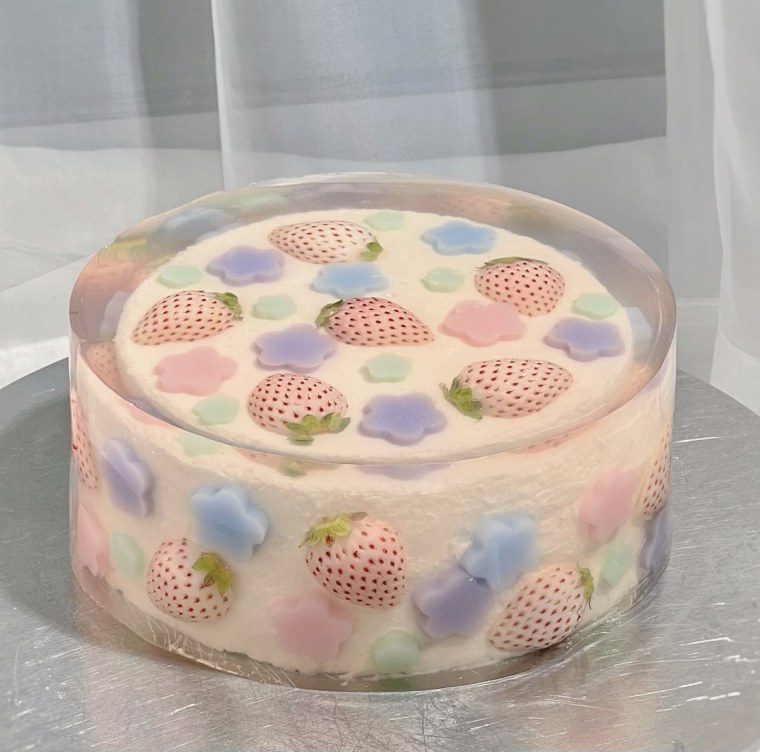

As far as its culinary value, its highest, non-ironic expression is probably in the beautiful Asian and fusion viral trends that turn up regularly. You may have seen the gravity-defying raindrop cake or photo-realistic 3D flower cakes, typically made with superbly transparent seaweed jelly called kanten or agar.

That gelled texture remains sought-after in many Asian cuisines, and it’s so worth seeking out to try if you’re unfamiliar. Hopefully you’re lucky enough to have a restaurant nearby to make such delights for you, but if not, the ingredients and recipes are widely available so you can try making them yourself. Soup dumplings, or xiaolongbao, rely on chilled, thickened broth so that the dough has something solid to wrap around before boiling. Anmitsu is a gorgeous Japanese kanten jelly with fruit pieces, azuki bean paste and dark syrup. If you’re just starting out, try a simple and delicate Laotian vun, a jelly treat made with agar and coconut.

It’s not just the food that’s traditional; the aesthetic roots of such trends are deeply classical, drawing from art like Korea’s Joseon dynasty paintings, Chinese silk brocades and Japanese ikebana. At the same time, there’s a movement toward saturated colors and designs reminiscent of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s dotted pumpkins among modern bakers and chefs. Even those molded American Jell-O salads have changed their colors and themes in step with modern art of the 20th century: the intricate art nouveau patterns in pepper strips and scallion flowers, the layered molds like color field Rothkos, the bright lights of fruit chunk pop art.

Aspic as an art form

So, incredibly, we’ve eaten our way through this subject to its heart of art.

Hamilton said her interest in aspic grew out of a love of vintage crafts, and she appreciates the ubiquity of primary source material; it’s easy for us to have fun exploring this culinary time capsule, because authentic recipes abound, and the ingredients are still on every grocery’s shelves. As a film production designer, she said, “I really approached my interest in it from an artistic perspective. What is interesting to me about (the recipes) is that you find them easily, so there were a lot made." She’s fascinated by why people of yesteryear were so into this particular food, whether it was economics or style. I often wonder what they could have been thinking myself, but as Hamilton says, "They are fun … maybe it was always just fun."

That fun is certainly foremost for gelatin artist extraordinaire Elrod (born Leanne Rodriguez), whose Mexakitsch studio speaks to my very soul. Her Instagram is not to be missed, and apparently a lot of people feel that way — she has over 30,000 followers. She makes life-sized resin replicas of molded salads, and some of them are electric lamps.

'The perfect combination of whimsy and nostalgia'

Elrod said she focuses on gelatin because it’s "the perfect combination of whimsy and nostalgia," noting that everyone will have some connection to it. Her own connection stems from time spent with her grandparents, and that’s true for many of her fans as well. She tells a story of one woman who told her one of the lamps reminded her of her grandmother’s "funeral salad" that was a staple of bereavement potlucks. Although her elaborate molds are limited to the eternal, inedible kind, she does "always keep a box or two of Jell-O in the pantry, because every once in a while I need a pile of emotional support Jell-O cubes to eat."

At the intersection of East and West, modern and traditional, is Lexie Park’s portfolio. Working under the name Nünchi, the designer arrived at the gelatin revival through art as well. She said she was familiar with vegan seaweed jelly from her family’s Korean food but never thought of it as an art medium to explore until the pandemic. Drawn to its motion and transparency anew, and looking to share aspects of her Korean culture, she started playing with it by preserving cosmetics and foods in jelly.

The explosion of gel in popular culture has paralleled her own interest. "It makes sense," she said, "because we’re in this pandemic time, and we’re all looking for things to make us happy." Before long, she found herself catering Los Angeles art gallery events for some big names and brands, like Ariana Grande and Nike. Although her initial focus on savory Asian-influenced appetizers abides, she also makes excellent use of jelly’s potential for sweet and bright desserts.

She doesn’t neglect flavor, adding yuzu, passion fruit and many other ingredients in unusual combinations, but what I find most compelling about Nünchi’s creations is their visual appeal. Scrolling through her Instagram is a kaleidoscope wonderland of cucumber ribbon cocktails, levitating berries and Bjork’s purple corn. Turning from eye-popping and ornamental to monochromatic and minimalist, yet always provocative, her style epitomizes the joys and contradictions of the new gelatin rage.

'It’s a very love-or-hate texture'

In commenting on why jellied textures are of the moment, she hits on something I think is central to its resurgence, too — it is polarizing. "It’s a very love-or-hate texture," she said, explaining that the controversial aspects can’t be separated from its overall appeal. Nünchi is looking to challenge conceptual frameworks as well as palates, so she has chosen the best possible muse. Looking at, touching and eating a texture you find at least a little bit upsetting makes it ripe for artistic expression; everyone is going to have a reaction.

There’s no sign of things slowing down for the gelatin renaissance, or for our three featured artists. Hamilton has her first Ambrosia Salad Soiree planned for this spring, and for the 2022 holiday Aspic Invitational, she’s going to ask entrants to focus on savory recipes. Due to demand, Elrod quit her long-term job to focus on her studio art full time earlier this year. Nünchi continues to book Los Angeles events but is looking to expand her experiential dinner offerings geographically, with pop-ups planned in New York and other states.

Jelly has a lot going on, literally and figuratively. The fact that you could eat it, at least if you wanted to, is the basis of its staying power, but why are we making art out of it? Why does it matter to us enough to want to immortalize it? Maybe it’s that where art like this deviates from reality, it actually improves on it. Artfully hovering inclusions, intensely colored, glass-like, with glitter and lights shining through — those things evoke the way the memory of The Gelatin Age feels. Or rather, the way we want those memories to feel. We want it to be true that it was real, a magical time when everything was shiny and clear and in its harmonious place.

In everyday life, it’s a pipe dream. But with belief suspended in gelatin, we can have the perfect past … and eat it, too.