Despite years of development, investment and progress in the Afghan media industry, 28-year-old Zahra Joya often found she was the only woman in a newsroom. “It was a lonely space, dominated by men who made the decisions about which stories were important, and which were not,” she says.

Joya, who is from the persecuted Hazara community, felt she faced discrimination because of her ethnicity and sex. “There were so few women journalists in Kabul,” she says. “There would hardly be women reporters covering political events or press conferences even though these stories affect us greatly.”

Q&AWhat is the Women report Afghanistan series?

Show

With Afghanistan under Taliban control, women’s voices have been silenced. For this special series, the Guardian’s Rights and freedom project has partnered with Rukhshana Media, a collective of female journalists across Afghanistan, to bring their reporting on the situation for girls and women across the country to a global audience.

Afghan journalists, especially women, face a dire situation. The free press has been obliterated by the Taliban, and female journalists have been forced to flee or have lost their jobs. Many of those still in the country are in hiding. Those who have escaped are now refugees facing an uncertain future.

All of the reporting in this series will be carried out by Afghan women, with support from the editors on the Rights and freedom project.

These are the stories that Afghan women want to tell about what is happening to their country at this critical moment.

Determined to disrupt this male-dominated landscape, in November last year, Joya started Rukhshana Media – a news website telling stories of Afghanistan’s women, written by Afghanistan’s women.

She chose the name as a tribute to the victims of Afghanistan’s patriarchy and all the women overlooked in the country’s history.

“In 2015, a girl named Rukhshana from Ghor province was accused of adultery and running away from home. She was escaping forced marriage,” says Joya. “The boy who accompanied her was given 100 lashes for ‘insolence’ for the same crime, but Rukhshana was stoned to death. Since the day I watched the video of her public stoning, her story stayed with me.”

In its brief existence, Rukhshana has told powerful stories of Afghan women’s struggle, offering the platform to local female journalists. They have written about women’s reproductive health, domestic and sexual violence, and gender discrimination, among other things.

“It is often the case that stories of Afghan women are decided by Afghan men or international journalists in the outside world. And while our presence in Afghan media is celebrated as an example of ‘women’s empowerment’, not much attention or space is given to us for defining what story should be covered,” Joya says.

“For example, Afghan media reports on rape cases, but they never report [on] what life looks like for survivors. That is what we are interested to tell,” she says. “At Rukhshana Media, we are trying to define the story from the perspective of Afghan women.”

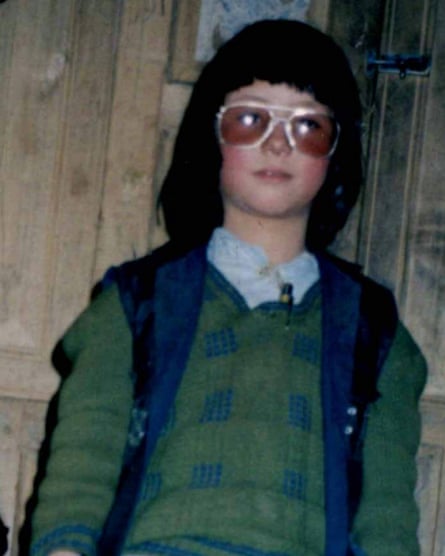

Joya’s journey to becoming a journalist was riddled with challenges. As a young girl, growing up during the Taliban regime in the 1990s, she was forced to dress as a boy to be able to go to school. “The Taliban had closed down all the girls’ schools and only boys were allowed to go. I was adamant I wanted to study, so I would dress up as a boy and took on the name ‘Mohammad’ and enrolled at the school,” she says.

“I do not want us to return to those days,” Joya says. “Which is why Rukhshana exists. It is my hope, my effort, to build a stronger Afghanistan which includes our voices, the voices of its women.”

But building, maintaining and growing even a small-scale media company such as Rukhshana is not easy. “Security is worsening and my reporters struggle with the challenges of reporting from the quickly changing frontlines,” she says.

Since Rukhshana’s inception last year, violence and extremist attacks have increased in Afghanistan , with almost 3,000 civilians killed in the conflict in 2020, according to the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission. This was accompanied by a series of targeted killings of journalists, government workers and state officials, which the Afghan government has largely blamed on the Taliban. A United Nations report from February, states: “Afghanistan is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists.”

Female journalists are at greater risk of assassination due to the issues they cover and their public role. In March, three young high school students were gunned down while working part-time for a news outlet in Jalalabad. In December a TV journalist and women’s rights campaigner was shot dead with her driver. As the Taliban advances across the country, female journalists have been forced to work in secret, using many pseudonyms to conceal their identity.

Funding is another challenge, says Joya. As an entirely self-funded initiative, it is hard to keep the project afloat, particularly as the situation in the country worsens.

“But I will try to keep it going for as long as I can. I see it as a source of hope for many women,” she says. “Afghanistan may not have much but it is our voice [of the media], and we must preserve it.”