At least 1 million people are, right this very moment, languishing in what the U.S. military has now deemed "concentration camps" in China. But recent attempts by U.S. officials and lawmakers to push for change have made little difference as a shocking human rights crisis continues to worsen.

In Congress' strongest move yet, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Wednesday passed the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act, which would require the creation of a report and a position within the State Department focused on China's crackdown. The bill, which also says President Donald Trump should condemn the abuses, will now head to the Senate floor.

"It is long overdue to hold Chinese government and Communist Party officials accountable for systemic and egregious human rights abuses," the bill's sponsor Florida Senator Marco Rubio said.

The bill's progression comes weeks after the Pentagon said it estimates that up to 3 million Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim minorities were being held in "concentration camps," one of the first times a U.S. official has used the term usually associated with the Holocaust. The label comes three years after China, in a bid to stamp out religious influence in the northwest region of Xinjiang, began arbitrarily placing Uyghurs in detention and building what has become an inescapable surveillance state.

"The Communist Party is using the security forces for mass imprisonment of Chinese Muslims in concentration camps," Randall Schriver, assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific security affairs, said at a press briefing. When asked about the phrase, Schriver said it was an "appropriate description" given the "magnitude of the detention… what the goals are of the Chinese government and their own public comments."

The Defense Department'snew position, which was unsurprisingly criticized by China days later, capped off several weeks of escalation over the issue by Beijing, Congress and the Trump administration. But a single event encapsulates how little success Washington has had so far.

At the end of March, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo met with four Uyghurs to discuss Xinjiang's human rights crisis. Within days, the aunt and uncle of one of those men, U.S. citizen Ferkat Jawdat, were moved from a detention camp and sentenced to eight years in prison.

Jawdat, whose mother was also moved from a camp to a prison, said it was clear from WeChat messages passed on to him from family friends that the punishments were doled out in retaliation for his meeting with Pompeo. The State Department confirmed to Newsweek it was aware and "disturbed" by reports of the retaliation.

"I have to shut up, I have to stay quiet. If not, I won't be able to see my mom or hear her voice again," Jawdat told Newsweek in April one of the messages said. Despite moving to the U.S. in 2011 with most of his family, Jawdat says China refused to give his mother a passport and is now threatening her safety and that of remaining family members to try to end his public protests—an incredibly effective strategy local officials have used to silence overseas Uyghurs in recent years.

"It's fairly clear that China engages in retaliation against Uyghurs overseas," Peter Irwin, a spokesman for the World Uyghur Congress rights group, told Newsweek.

In February, hundreds of Uyghurs and other ethnic Muslim minorities shared photos of their loved ones online as part of the #MeTooUyghur movement. According to Irwin, the widespread attention is something China wants to prevent from happening again. "China likely would like to re-instill this fear in the diaspora community that has been largely absent over this period."

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who co-sponsored a House version of the Uyghur bill, told Newsweek that "the jailing of the relatives of a U.S. citizen for engaging in dialogue with the American government to pursue a more hopeful future is an affront to the basic ideas of justice, human rights and human dignity, and must be condemned by all."

"The unabated oppression that the Uyghur community faces at the hands of China is a stain on the conscience of the world," she said.

Three trauma-soaked years

"Everything is going in the worse direction," says Jawdat.

Xinjiang began sending residents to extrajudicial "re-education" camps in 2016 for transgressions as vague as observing religious practices like Ramadan and as minor as having a beard, buying a SIM card or speaking to family overseas. Since then, the State Department says there have been reports of torture and "instances of sexual abuse and death." Some experts fear the situation devolving into genocide.

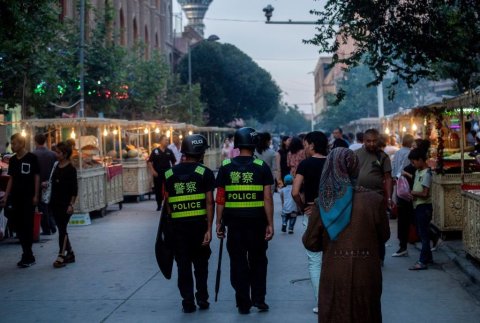

Outside the camps, Uyghurs generally cannot leave Xinjiang, let alone China. Facial recognition technology is omnipresent and Uyghurs are banned from entering many public spaces and shops. Party officials have lived in their homes and others have forced Uyghurs to eat pork. Mosques and graves have been razed. And earlier this month Human Rights Watch released a report about a mass surveillance app that aggregates everything from blood type to electricity usage and package deliveries, alerting authorities to suspicious behavior.

But the recent development with Jawdat not only highlights potential consequences for the families of Americans who dare meet with U.S. officials about the crisis, but illustrates the troubling next stage of China's crackdown as more detainees are transferred to prisons in Xinjiang and beyond.

"[They're] basically being redistributed across China proper where they kind of disappear off the radar because the spotlight is on Xinjiang at the moment," Joanne Smith Finley, an expert on China and the Uyghur identity at Newcastle University, told Newsweek. She added that many people are sent to high-security prisons where they're "kept in shackles the whole time."

"I personally think things have got worse," she said.

Radio Free Asia (RFA) confirmed the transfer of detainees to other provinces in February. One prison official told RFA that the number of detainees transferred out of Xinjiang is "huge." "They are not here because they committed certain crimes, but for a special reason, and they are under particularly heavy security," the official said.

In Xinjiang, Jawdat says his relatives, including his grandmother, have been "threatened by the Chinese police" and forced to sign agreements that they won't talk to people in the U.S. Local police have shown family members his picture to scare them into not talking with him and or even mentioning his name.

Like many Uyghur activists overseas, the attention came after a decision to speak out about the detention of loved ones. Jawdat said his mother was held for 22 days in November 2017, before she was initially released.

"But her phone was taken away by the Chinese police at the time. And she was so scared," Jawdat said. "She'd just call us again and she doesn't say anything. We just look at each other and then she starts crying. I can see the fear in her eyes." His mother also mentioned she was risking getting into trouble when they were talking, "so that means she knew somebody was monitoring her and maybe listening to her phone calls."

On February 6, 2018, Jawdat says he received a message from his mom saying she was going away again and "she doesn't know if she can come back or when she can come back. And then she was crying from beginning to end."

On Wednesday, Jawdat said on Twitter that his mother called him last week to say she had been released and told him to stop criticizing China. But the next day she was returned to the camps. And Jawdat believes police were with her—and listened in on their conversation—the whole time.

"Again, China is using my mom as hostage to silence me but this time using my mother's voice directly," he wrote.

Smith Finley has been traveling to Xinjiang since 1995 and says the changes she saw on her most recent trip in 2018 were palpable.

"Fear, absolute fear. Terror, trauma, people crying in the streets once they realized that I knew the 'situation,'" she said. "I've never seen it like that ever." Most of Smith Finley's contacts wouldn't even take her calls and only two would meet with her—agreeing to do so only if it was after sundown and they kept moving while they spoke. "We would have to change our conversation every time we approached one of the convenience police stations because of the audio surveillance," she said.

Many Hui Muslims and other ethnic minorities in China are now concerned that the repression fine-tuned by authorities in Xinjiang will be exported across the country, a future that concerns Jawdat.

"There is no way the Chinese government is going to stop on the Uyghurs only," he said. "I can tell you, 100 percent right now, that this will be written in the history books as a genocide that happened in the 21st century."

U.S. efforts have achieved little

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo may have described China's practices in Xinjiang as "Orwellian" several times during April, but his department has yet to make any public indications about sanctioning officials involved in human rights abuses. Activists believed sanctions would be forthcoming in December but were left disappointed, with many experts believing the trade talks have taken priority in the Trump administration.

Earlier this month when pressed during television interviews, Pompeo refused to confirm when or if sanctions will be imposed at all, saying only that he had "raised" the issue with his counterparts in Beijing.

"The language everyone is speaking is money. The language everyone is speaking is bilateral trade," Smith Finley said, adding that sanctions like those instituted against South Africa in 1986 over apartheid would likely be effective. "And this is turning into, in some ways, a comparable situation because what the Chinese state is doing in Xinjiang is thoroughly racist."

U.S. lawmakers have urged a similar approach. On April 3, Rubio, who co-chairs the Congressional-Executive Committee on China, led dozens of bipartisan lawmakers, including Massachusetts Senator and 2020 Democratic candidate Elizabeth Warren, in requesting Magnitsky sanctions against Chinese Communist Party officials involved in Xinjiang's human rights violations. In a letter, the lawmakers also said they were "disappointed" with the administration's "failure" to already do so.

"The Communist Chinese government is committing crimes against humanity as it detains over a million Uyghurs and other religious and ethnic minorities in so-called 're-education' camps and expands its Orwellian high-tech surveillance state in Xinjiang," Rubio told Newsweek. The Florida Senator also wants to strengthen export controls and financial transparency requirements to ensure American products and investments are not enabling "China's growing Orwellian digital authoritarianism" and human rights abuses.

The day after the letter was published, freshman Muslim congresswoman Ilhan Omar tweeted her support, "These are crimes against humanity and anyone responsible must be fully held to account. Words alone are not enough."

Experts who spoke with Newsweek agreed more action is needed but criticized both Democrats and Republicans for not yet passing any legislation or sanctions targeting Xinjiang.

The Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act, co-sponsored by more than 90 bipartisan lawmakers across the House and Senate, is still far from passing. And experts say more needs to be done to affect real change.

"This is a drop in the ocean of course," Smith Finley said. "It's very easy for China to discredit the U.S. right-wing politicians by saying, 'They don't really care about human rights, they don't really care about the Uyghurs at all, they only care about their trade war with us and they only care about containing China.

"So what we need is for the left to make much, much more noise. We need the Democrats to make much more noise in the U.S. and we need the left-wing across the world generally to make much more noise… What we've got is the American right-wing threatening to levy the Global Magnitsky Act but not doing so. There's no point threatening to levy it if you're not going to actually levy it. China's just sitting there laughing, saying, 'Well, do your worst' but yet you're not doing anything," she added.

Max Oidtmann, an expert on the Chinese Communist Party's policy toward Muslims and Islam at Georgetown University Qatar, raised the same point.

"From the perspective of China's domestic audience, Republican senators are simply grandstanding and have no moral legs to stand on so long as the Trump administration continues its own mass detention of Latin American migrants and separates children from their families," Oidtmann said.

China is emboldened because it can be

Beijing initially denied the existence of Xinjiang's detention centers before, late last year, suddenly claiming they did in fact exist but were just harmless vocational training centers. The country faced little blowback, either then or now.

"China is being more brazen because China can be more brazen because no one is holding China properly to account," Smith Finley said. "And China perceives this very clearly."

Part of the reason for this boldness is the repression in Xinjiang has basically received the seal of approval fromleaders of two of the largest majority Muslim countries, Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan. The Saudi Crown Prince defended China's actions in February saying the country has "the right to carry out anti-terrorism and de-extremization work for its national security" while Khan has dodged questions on the issue, saying he doesn't "know much."

At this stage without U.S. sanctions, Irwin still believes that international pressure from neighboring countries, including Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Iran, Turkey, and the Gulf, are the best hope for change because this is where the Chinese government is "much more concerned about its image" as well as the future of Xi's signature global infrastructure project, the Belt and Road Initiative (in which Xinjiang, coincidentally enough, sits at the heart).

Until more countries take action, experts remain concerned about escalating abuse and torture. For Oidtmann this is particularly troubling as growing facilities require staffing of "thousands" of poorly trained guards. "I also foresee increasing abuse within these detention centers as local and national budgets for running them come under greater and greater economic pressure," he said.

But even if new directives were ordered at the national level, there really is no telling how the situation in Xinjiang would unfold. It brings to mind an Uyghur saying repeated by Smith Finley about Beijing policies becoming unrecognizable once they reach the local level.

"If I ask him to bring me his doppa [skull cap], he brings me his head."