On the anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule, a large group of protestors smashed through glass doors and stormed the government headquarters. The dramatic July 1 events have marked a break from Hong Kong’s peaceful demonstrations against a controversial extradition bill.

Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam condemned the violence in an early Tuesday morning press conference and pledged to take necessary legal action.

“We saw two completely different scenes: one was a peaceful and rational parade… the other one was a heartbreaking, shocking, and law-breaking scene,” she said.

“Nothing is more important than the rule of law in Hong Kong.”

Just hours earlier, several hundred mostly young activists occupied the Legislative Council building for hours. They ransacked desks and filing cabinets and tore down portraits. They raised a black banner, that read: “There is no way left,” mounting an open challenge to China and to Lam.

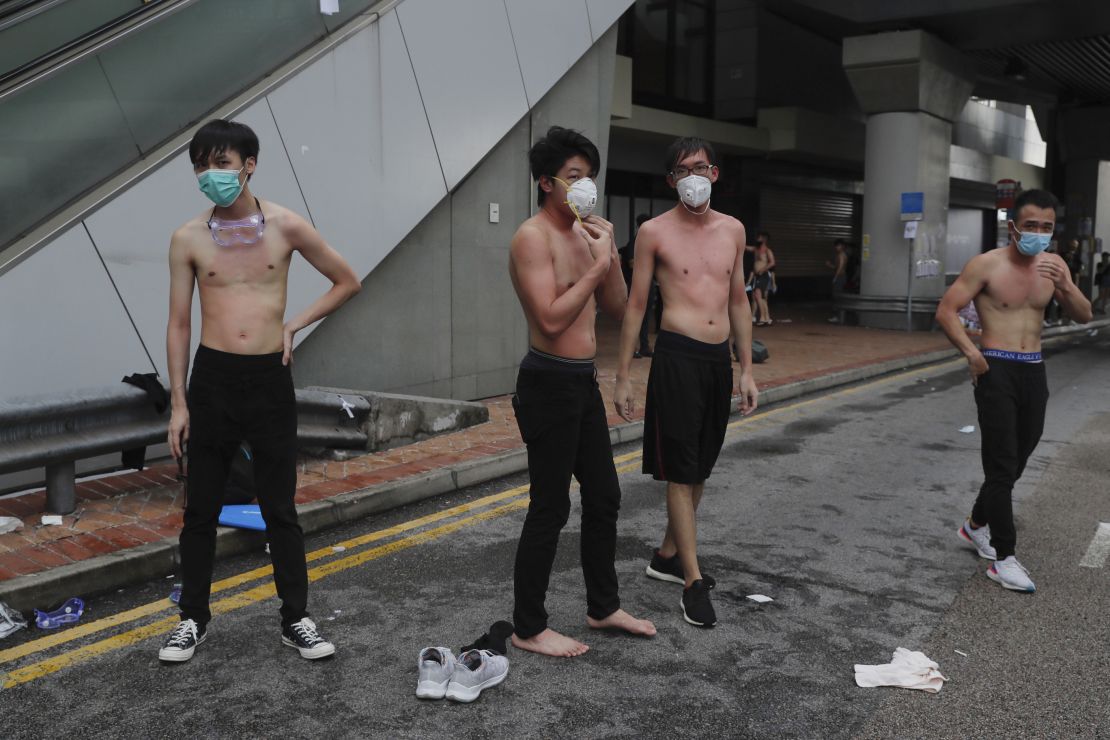

Within minutes of protesters taking a collective decision to exit the building, police fired tear gas and used baton charges to disperse the crowd. Thirteen police officers were ultimately hospitalized after clashing with protesters, Police Commissioner Lo Wai-chung said Tuesday.

“Hong Kong is a safe society and none of this violence is acceptable” he said, adding “police had no choice but to retreat” at moments.

The extradition bill that sparked public outrage

Monday was the 22nd anniversary of the semi-autonomous city’s return to Chinese sovereignty. The date is marked annually with protests calling for greater freedoms.

This year, however, escalating anger over the extradition bill boiled over into a pointed rebuke of Chinese rule.

Critics feared the extradition bill could be used to send residents to mainland China for political or business offenses. After earlier protests, the extradition bill was shelved. But protests have not stopped, amid calls to scrap it completely.

Lam said Tuesday there are no plans to restart the legislative process before it expires in 2020.

Protesters’ demands include the full withdrawal of the extradition bill and universal suffrage so the people have the right to vote for their chief executive and legislative council.

Protesters used trolleys as battering rams to bust through the entrance, pry open metal shutters and occupy the government building. They set up barricades and opened a line of umbrellas in an attempt to hold the complex, but left en masse shortly after midnight, as hundreds of riot police began to descend on the site.

Spray-painted messages in Cantonese and English on the walls of the legislative chamber called Lam’s government a “murderous regime” and declared “Hong Kong is not China.”

The protestors’ siege of the Legislative Council building was starkly different than a peaceful march just one street over, on the same day, where tens of thousands of Hong Kong citizens carried signs calling for greater democracy and an end to the extradition bill.

Protesters had hoped to block or interrupt an official flag raising ceremony marking the occasion, attended by Lam.

The ceremony was a rare public appearance for Lam, who was recently forced to publicly apologize for the introduction of the extradition bill last month which sparked public outrage.

In her speech at the flag-raising ceremony Monday, Lam promised to “ease anxiety in the community, and to pave the way forward for Hong Kong.”

Protesters occupying the Legislative Council building on Monday hoisted a British-colonial-era flag, calling for more democracy – the main demand of the 2014 Umbrella Movement, which immobilized the city’s financial district for 79 days.

Many in Hong Kong see the extradition bill as eroding special freedoms afforded to them under the “One Country, Two Systems” model, which was created during Hong Kong’s handover from British to Chinese rule in 1997. The city maintains distinct and independent rule of law to China as part of that framework.

Protesters also want to end characterizations of earlier protests as riots, and have called for the creation of an independent commission to look into accusations of police brutality.

Many protesters are still angry over police use of tear gas and rubber bullets to force people off the streets on June 12, when protesters successfully blocked off the city’s legislature and prevented lawmakers from debating the extradition bill.

Beijing said on Monday that Britain has no responsibility toward the former colony and must stop interfering in what is a Chinese domestic affair. UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt said on Sunday that Hong Kong must maintain its “high degree of autonomy.”

Beijing stands behind controversial leader Carrie Lam

While Beijing has stood by Lam, she is facing criticism from all sides for her handling of the crisis.

Lam says the bill was her idea, not Beijing’s, and she has taken responsibility for a rushed roll-out and failure to communicate with the public.

Even much of the city’s business community, traditionally conservative and unwilling to get too involved in politics, came out against the bill, and some pro-government figures criticized Lam for pushing it through the legislature against proper procedure.

Lam justified that move as necessary in order to extradite a wanted murderer to Taiwan, but that justification was undermined by Taipei’s statement in May that it would not accept any transfer under the controversial bill.

Protests and anger over the bill reinvigorated an opposition movement that had appeared to be in the doldrums after repeated losses in the wake of the 2014 Umbrella Movement.

Now Lam is facing not only continued demonstrations against the bill – and demands for her resignation – but also a return to the issue behind the 2014 protests: that Hong Kongers are not able to choose their own leader.

A key reason Beijing was keen to keep Lam in place, even if she wanted to resign, is that losing her would require choosing another chief executive within six months. Currently that is done by an election committee heavily stacked in Beijing’s favor, and renewing this process would be sure to restart an angry political debate that had been safely kicked down the road to 2022.

Now that issue seems to be coming to the fore anyway, piling more pressure on Lam and creating new headaches for her bosses in Beijing.