Does Climate Change Cause More War?

A new paper questions the growing body of evidence that weather fluctuations can prompt wars, but researchers have doubts about its value.

Updated on February 13, 2018

It’s one of the most important questions of the 21st century: Will climate change provide the extra spark that pushes two otherwise peaceful nations into war?

In the past half-decade, a growing body of research—spanning economics, political science, and ancient and modern history—has argued that it can and will. Historians have found temperature or rainfall change implicated in the fall of Rome and the many wars of the 17th century. A team of economists at UC Berkeley and Stanford University have gone further, arguing that an empirical connection between violence and climate change persists across 12,000 years of human history.

Meanwhile, high-profile scientists and powerful politicians have endorsed the idea that global warming helped push Syria into civil war. “Climate change did not cause the conflicts we see around the world,” Barack Obama said in 2015, but “drought and crop failures and high food prices helped fuel the early unrest in Syria.” The next year, Bernie Sanders declared that “climate change is directly related to the growth of terrorism.”

If you live on a planet expecting changes to temperature or rainfall in the coming decades—which will come faster and stronger than the many natural climate changes of the past—it’s all a bit worrying. So a paper published Monday in Nature Climate Change might seem like a nice respite. After undertaking a large-scale analysis of more than 100 papers published on the topic, the article argues that the connections between climate change and war aren’t as strong as they seem—that the entire literature “overstates the links between both phenomena.”

Phew, you might think, maybe things aren’t so bad.

Except that—to hear scientists who study the issue tell it—the paper does not make its own case as strongly as it may seem at first. “I can’t see what the authors are trying to accomplish with this article,” says Elizabeth Chalecki, a political scientist at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

The paper arrives into a field deeply polarized between researchers who endorse a link between climate change and violence and those who reject one. For scholars who approve of the link, the paper doesn’t prove its point or even say much of anything new. And while researchers who rebuff the link are more charitable to the paper, they also do not think it throws the field’s most famous studies into question—because they already questioned the veracity of that work.

“Some may read this paper as saying that there’s lots of literature that says climate change causes conflict, and that this literature is based on sampling errors,” says Jan Selby, a professor of international relations at the University of Sussex. “But even before this paper, there was huge disagreement about what links could be made between climate change and conflict. And irrespective of the question of sampling error, I think the evidence in many of those papers is really weak.”

First, though, to the paper itself. The authors attempt a large-scale analysis of the entire field of conflict and climate-change research. To do this, they searched an enormous academic database for certain keywords—like climate, war, weather, and unrest—then pruned the thousands of articles that they found down to a slim 124 that substantively addressed the connection between the two topics. Then, they analyzed the resulting body of papers for the names of certain countries and regions.

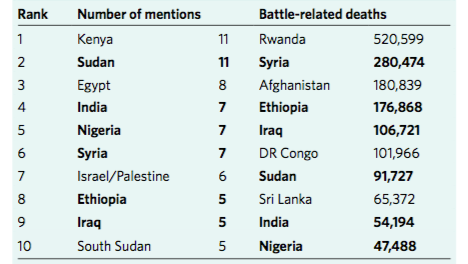

After running this analysis, the authors conclude that the entire field is biased in two ways: toward countries that are easy for English-speaking researchers to access, like Kenya and Nigeria; and toward countries where conflict has already erupted, like Syria and Sudan. They also say that the literature focuses too much on Africa, ignoring vulnerable countries in Asia and South America.

The countries that were mentioned most in the climate-conflict literature included Kenya, Sudan, Egypt, India, Iraq, and Israel and the Palestinian territories. (Though even the two most-mentioned countries, Kenya and Sudan, only appeared in 8.8 percent of all papers.)

That list shares very little overlap with a list of countries that should theoretically be the most vulnerable to climate change, which includes Rwanda, Honduras, Haiti, Myanmar, and the tiny Pacific island nation of Kiribati. But it is quite similar to a list of the countries that have suffered the most combat-related deaths in the last quarter-century.

“If we only look at places where violence is, can we learn anything about peaceful adaptation to climate change? And if we only look at those places where there is violence, do we tend to see a link because we are only focusing on the places where there is violence in the first place?” asked Tobias Ide, a coauthor of the paper and a peace and conflict researcher at the Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research.

He believes the study throws both the quantitative and qualitative research on the question into doubt. The qualitative research suffers from “the streetlight effect,” an overreliance on English-speaking former colonies in Africa where it is easier to do research, he says. (The “streetlight effect” refers to only looking for your keys—or anything else—where it’s easiest to see in the dark.) Quantitative research, he says, is ailed by “sampling on the dependent variable”: that is, only studying war in places where there is already war.

Ide and many other researchers worry that such research will eventually harm the people that live in the places that are being studied. “In Sudan, Kenya, Syria, people say climate change is causing conflict, and that it will cause more conflict in the future because of droughts and stuff,” Ide said. “This scares investors away. People don’t want to invest there anymore because they’re scared these places are biased, or immature, or barbaric.”

Ide also fretted that this will encourage Western philanthropists or militaries to unseat local power in these countries, in effect saying, “You can’t do it on your own, so we have to move in and manage your resources.”

“I’m not saying that everyone who focuses on climate change in Syria or Kenya is automatically promoting colonial behavior, but if there’s a connective frame it might well facilitate this kind of thinking,” he told me.

Ide demurred when I asked where this kind of climate-science-driven colonialism has already happened. “If it comes to proving that a certain academic framing had an influence on people’s mind-set, or eventually even actions or policies, that’s really hard to pin down or prove empirically. People don’t just read academic studies—they watch television, they listen to peers,” he said. But he also said that the push to fortify southern Europe and adopt much more regressive immigration policies was driven, in part, by the climate literature.

“From what I’ve heard from colleagues working on the issue, the idea that climate change is leading to conflict and migration in the Middle East—that is used by some conservatives and lobbyists and politicians in Brussels to inform stricter border controls in the south of the European Union, like not saving [refugees] in the Mediterranean Sea,” he told me. “It’s still anecdotal evidence, but it’s there.”

His paper fits into a broader pattern of researchers—especially those in Europe—rejecting links between global warming and war. Selby, the Sussex professor, and a number of his colleagues published a blistering article last year attacking the idea that a climate-addled drought in any way pushed Syria into war. It argued that a prewar drought—which supposedly prompted the country’s economic chaos—was not as historically anomalous as claimed; and that the farmers who fled that drought had little involvement in the run-up to the war itself. He called the new article “a decent paper” without “obvious flaws.”

“But I guess that’s probably to some extent because it confirms suspicions that I have anyway,” he said. He told me that there was “no consensus” in the quantitative literature on whether climate change exacerbates conflict. “Some people claim there is a consensus, but they only do so by ignoring a huge amount of literature and standing on what I think are spurious methodological grounds.”

He said that conflict-climate scholars should study climate-vulnerable places where there has been no conflict as well as war zones. “If you go study in Costa Rica or Greenland, for example, then you will find a different correlation. And it will make the case as well.”

“I don’t think there’s anything novel or particularly unusual in [the new paper],” says Simon Dalby, a professor of politics and climate change at the Balsillie School of International Affairs. “The focus on Africa—Africa, Africa, Africa, Africa—has been noted for years by those of us tracking this. And the ‘street lighting’ point is well taken. Kenya is easier to get into for lots of folks doing the research, who are mostly white-skinned Northerners who speak English,” he says.

Dalby takes something of a middle ground on the dispute. Going back to the 1990s, he says, a body of literature has “made it clear that environmental change might—in some complicated series of circumstances—lead to conflict, but it was the intervening circumstances that really mattered.”

Another researcher who has harped on the focus on Africa is Solomon Hsiang, an economist and professor of public policy at UC Berkeley. In 2013, he and his colleagues noted the preponderance of Africa-focused research in a now-famous study that argued there was an empirical link between conflict and climate change. For every change of a standard deviation in temperature or rainfall, he and his colleagues found that the chance of violent conflict between groups rose by 14 percent.

“There is nothing really surprising or new in this study,” he said in an email. “Studying conflict-prone regions isn’t a problem, it’s what you would expect. Nobody is studying Ebola outbreaks by studying why Ebola is not breaking out in cafés in Sydney today, we study what happened in West Africa when there was an actual event.”

Hsiang also lambasted the article’s method of analyzing the literature as a whole to claim that researchers “[overstate] the links between” conflict and climate change.

“The biggest issue with the study is that they strongly insinuate there is some kind of bias boogeyman in the research field without actually showing that anybody else who came before made an error or demonstrating how their idea could affect findings in the field,” he told me. “They are vague and imprecise about their critique of prior work, without identifying which actual findings they are overturning or replicating anybody’s work. Instead, they simply allude to an aroma of a problem in the research field, which sows doubt without providing actual evidence.”

The article itself appears to back off its claims by the end of the paper, saying that its findings are not intended to discredit any one researcher or study. “We are not saying that the correlations are invalid or invaluable, nor are we accusing any studies or authors who have focused on specific regions,” Ide told me. But the paper nonetheless claims that the conflict-climate link is overstated.

Chalecki, the University of Nebraska political scientist, also finds the paper’s focus odd. It makes sense to study places where there is war, she says: “Violence isn’t an inherent condition in domestic politics or international politics. We don’t need to explain peace. It’s conflict, it’s war, that we need to explain.”

She also wonders if the “streetlight effect” that preoccupied the authors was simply a tendency of academia, since authors tend to cite prior work on a topic. Academics focus on war zones because it matters how the war starts, she says. “In terms of policy-relevant research, I don’t think there is anything in this article that might help a country or region offset climate change,” she says. “If I’m talking to an undersecretary of defense, or a policy maker, they’re gonna look at this [paper] and say ... what does this even mean?”

“I thought it was a weird article,” says Greg Petrow, another political scientist at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, who specializes in quantitative methods. He says the paper—which focuses on sampling bias in the field—suffered from sampling bias itself.

“They’re not really directly assessing what they want to be assessing. They’re trying to assess sampling bias, but they’re looking at the sampling as a dependent variable. They’re actually looking at publication bias as an independent variable,” he says. There are papers that study publication bias, he added, but they don’t cite or refer to them.

In an email, Ide pushed back on some of these criticisms, saying that a peaceful “control” population was more useful than a study on Ebola in Sydney coffee shops. “Most studies on cancer, for instance, include a large number of different people not suffering from cancer as control cases in order to avoid premature conclusions, but also to identify the factors which make people resilient to cancer,” he said. “ I think the same logic should apply to climate-conflict research.”

Above all, he said, his paper showed how much more scholarship on the link can still be done. “I was a bit surprised that even within American studies, there’s not really a focus on Latin America, basically,” he told me. “You can be concerned about Iraq, Syria, or India because of geopolitical relevance—but why not look for [climate-related conflict] in Mexico, or Honduras, or Brazil? Because that would have much sharper consequences for the United States.”

These gaps may even have policy implications. “If I were a decision maker in Washington, D.C., concerned about climate change and conflict, I would like to know whether our knowledge on the issue rests on a solid foundation, and I would be rather concerned to learn that we know a lot about Kenya in this context, but very little about vulnerable countries in the U.S.A.’s neighborhood, such as Mexico and Honduras.”

Dalby, the political scientist, tried to take a broader view of the dispute—and of the climatic upheaval that could come later this century. “Looking for these empirical connections is all very well and good,” he told me, “but if you’re looking for the causes of climate change, it’s us—the overconsuming, fossil-fuel-burning North and West. If you want to get serious about climate change, worrying about the small-scale details of conflicts in Africa is missing the point. It’s us.”