Where are the most dangerous places in the world to be lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT)? It’s not an easy question to answer.

“Comprehensive data on hate crimes and state-sponsored violence against LGBT people is just non-existent in a lot of countries,” says Jessica Stern, executive director at OutRight International, an advocacy group. “The most consistent violence tends to actually be where there is the least government documentation [of violence], and the least civil society presence.” Homosexuality is still a crime in 72 countries (pdf). And even countries with no legal barriers, such as the US, record shocking levels of hate crimes – there were 53 transgender murders from 2013 to 2015 and not a single one was prosecuted, for example. Based on the data that is available, here are seven of the countries where LGBT rights are most under threat – but where campaigners are also making the occasional small step of progress.

Iraq

“It depends on what part of the country you are in – but in two words I’d describe Iraq as ‘not safe’ for LGBT people,” says Amir Ashour, Iraq’s only openly gay activist, explaining that it’s not just the threat from Islamic State in Mosul and Hawija. “In Baghdad and the middle of Iraq the violence is actually more visible from groups supported by the government, who do killing campaigns. The latest one was in January – we knew several people who were killed but there were rumours there was a list of 100 names.”

Attacks on gay individuals under Isis have been widely reported, but Iraq’s systematic killing campaigns of gay individuals pre-date the terror group and continue to this day. Ashour, founder of LGBT group IraQueer, estimates there’s been at least one a year since 2006.

Suspected community spaces have been burned down or bombed, and it hasn’t been safe to meet up with people for at least six years – especially as people have been targeted via dating apps. “We have no spaces left online or offline,” Ashour adds sadly.

It’s clear LGBT Iraqis are still looking for ways to connect though. Ashour says his NGO’s network has grown really fast with the organisation’s website getting 11,000 hits a month, most from inside Iraq. “What’s great is that we’re able to provide resources for LGBT Iraqis that were not there for ourselves.”

There’s hope for change too. A rare opportunity for Iraqi activists has come up with Iraq being appointed to the UN human rights council. “The officials used to say they could never meet with us but now they can’t say they’re busy because protecting our rights are part of their job,” he jokes.

Iran

Iran’s leaders describe homosexuality as “moral bankruptcy” or “modern western barbarism”. Amnesty International estimates that 5,000 gays and lesbians have been executed there since the 1979 Iranian revolution. Although it is less common now, it still occurs. In the summer of 2016 a 19-year-old boy was hanged in Iran’s Markazi province: in 2014 two men were executed.

The threat of blackmail is now a huge problem for gay men, explains Saghi Ghahraman, founder of the Iranian Queer Organization. This is because Iran’s complex laws around homosexuality mean that men face different punishments for consensual sexual intercourse, depending whether they are the “active” or the “passive” participant. The passive person faces the death penalty, but the active person only faces the same punishment if married. The laws can lead to distrust between partners, as if caught, the only defence for the passive partner is rape. This also creates an atmosphere for blackmail.

And in a remarkable piece of legislation, fathers and grandfathers are given the right under Iranian law to kill their offspring, making “honour” killings legal. “From an early age, children learn starting in the home that the world is very hostile to LGBT people,” says Ghahraman.

The government’s treatment of the transgender community is not so black and white. Since 1983, when Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa permitting the acceptance of transgender people in society, sex reassignment surgery has been available and Iranians can take out loans for the surgery. In fact, except for Thailand, Iran carries out more sex reassignment operations than any other country in the world. It’s a double edged sword for some in the LGBT community though – the operations have become a controversial solution for gay men trying to reconcile their faith with their sexuality and the government refuses to recognise transgender people who don’t want surgery.

Honduras

A global study found that Honduras had by far the highest numbers of transgender murders relative to its population. But it’s not just trans people who are at risk. After the left-leaning president, Manuel Zelaya, was ousted in 2009, LGBT murders soared; 215 have taken place since the coup.

It’s important to understand the wider context too – in recent years, people have been able to kill with impunity, regardless of the victim’s sexuality, and Honduras today is murder capital of the world with a national homicide rate of 60 per 100,000 people. But LGBT murders are more likely go unpunished, according to an Inter-American Commission on Human Rights report (pdf), due to discriminatory stereotypes popular among the police.

Interestingly, despite the threat of assassinations, LGBT Hondurans are active both in civil society and politics. When René Martínez was murdered last June, he was a member of President Juan Orlando Hernández’s ruling National party.

LGBT activist Erick Martínez is also a candidate for the Honduran congress. He says things are improving but there are still challenges: “We started getting LGBT activists elected in 2012 and we are now seeing the fruits of that as we have more LGBTI people able to influence the political parties for real inclusion.

“The biggest problem is to make generational relays as because of the violence many LGBTI activists are migrating and one of the fears I live up to is being a victim of the violence for the work I do.”

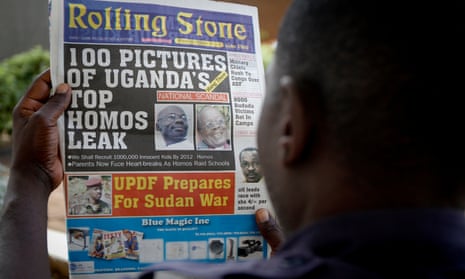

Uganda

The number of LGBT refugees a country produces is another indicator of how dangerous a country is for LGBT people. Between 2014-2016, the Friends Ugandan Safe Transport Fund, a US-based Quakers association, reports that they supported more than 1,800 LGBT individuals to escape Uganda.

It’s easy to understand why people want to leave. In 2014, the Ugandan government attempted to introduce the controversial Anti-Homosexuality Act, which at first included a provision for the death penalty. It would go on to be declared unconstitutional in Uganda’s courts, but the damage was done, and homophobic violence had been legitimised. People were outed in Ugandan newspapers, one published a list of “top 200 homosexuals”, despite knowing that revealing LGBT people’s identities could lead to them being killed. A report by the Ugandan NGO SMUG showed that persecution based on sexual orientation had increased in the two years after the act.

Ugandan activists refuse to be pushed underground, despite the risks – they put on a week of pride events last summer that were disrupted by police.

Russia

A gay scene with regular events is tolerated in Moscow. But Putin’s government is openly anti-gay, and is discussing another homophobic law, which proposes jailing people for public displays of non-heterosexual orientation or gender identity.

LGBT groups have been denied the right to hold pride marches under anti-propaganda laws and well-publicised events that have been held have been disrupted by violent thugs. Nor has any action been taken to shut down groups that openly go after LGBT people, such as Occupy Pedophilia, a national network of Russians who torture gay men, and then post hugely popular videos of their acts online.

Egypt

Egypt is widely regarded as being the biggest jailer of gay men – the New York Times estimated at least 250 LGBT people have been arrested since 2013 while LGBT blog 76 crimes estimates that that number could be closer to 500.

Being gay or transgender is not illegal in Egypt, but ever since the military pushed out the president Mohamed Morsi in 2013, the authorities have engaged in a crackdown on the LGBT community, imprisoning them on the charge of “debauchery”, which comes with a jail term of up to 17 years. Traditional meeting spots are increasingly unsafe, and since 2014 gay dating apps such as Grindr have been warning their Egyptian users that “police may be posing as LGBT on social media to entrap you”.Police have been known to invite journalists and cameramen along on raids; those caught may be outed to the whole country, even if arrested by mistake. In 2014 26 men were filmed as they were arrested naked and accused by a TV presenter of leaving a homosexual brothel. All 26 men were later acquitted but the repercussions of the case led to one man attempting to burn himself to death.

Nigeria

Of the people interviewed for the ILGA-RIWI Global Attitudes Survey on LGBTI People (pdf), 51% said they “strongly agreed” with the statement “being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender should be a crime” making it the most homophobic country of the 45 surveyed.

The country threatens 14 year prison sentences for homosexual acts, and under a law passed in 2013, any Nigerian who belongs to a gay organisation can also be liable for a 10 year jail term. These laws, along with Sharia law in Muslim areas of the country mean it’s not safe to publicly identify as LGBT in many parts of Nigeria.

But for Olumide Makanjuola, executive director of The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERS), it is social acceptance that is a bigger issue than legal protection for the LGBT community. “You can have all the laws you want but it doesn’t matter unless you have social acceptance of LGBT individuals,” he says, explaining that as an overly religious country with a population of 182 million, any engagement needs to be at a critical mass level to change attitudes.

“For every 100 politicians for example you might have one who’s progressive, but election campaigns are closely tied to the religious system, so if a politician gets into power with the help of the church or the mosque, he feels an obligation to them.”

He adds, however that Nigeria has progressed a lot: “The fact is 10 years ago we couldn’t be having this conversation. But today we have LGBT organisations that are visible en masse, we’re able to hold public events and we can do community engagement.”

Additional reporting by Naomi Larsson.

In February the Guardian Global Development Professionals Network is highlighting the work of the LGBT rights activists throughout the world with our LGBT change series. Join the conversation at #LGBTChange and email globaldevpros@theguardian.com to pitch an idea.

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow @GuardianGDP on Twitter.