In August 1914, French troops fired tear-gas grenades into German trenches along the border between the two countries. While the exact details of this first tear-gas launch are fuzzy, historians mark the Battle of the Frontiers, as World War I’s first clashes between France and Germany came to be known, as the birthday of what would become modern tear gas.

This early tear gas had resulted from French chemists’ efforts, at the turn of the 20th century, to develop a new method of riot control while maneuvering around international treaty restrictions imposed on “projectiles filled with poison gas” by The Hague Conventions of 1899.

Designed to force people out from behind barricades and trenches, tear gas causes burning of the eyes and skin, tearing, and gagging. As people flee from its effects, they leave their cover and comrades behind. In addition to its physical consequences, tear gas also provokes terror. As Amos Fries, chief of the U.S. Army’s Chemical Warfare Service, put it in 1928, “It is easier for man to maintain morale in the face of bullets than in the presence of invisible gas.”

Today, tear gas is the most commonly used form of what's known in law-enforcement jargon as “less-lethal” force. Journalists file news stories of tear-gas deployment so regularly that pictures of smoke-filled streets have come to feel like stock photography—a theatrical backdrop of protest. Just this week, police in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson deployed tear gas to disperse crowds protesting the killing of the unarmed teenager Michael Brown by an officer. Desensitized to these images, people often forget that tear gas is a chemical weapon, designed for physical and psychological torture.

So how did this substance, first deployed in war, make it from the trenches to the streets?

The process began before World War I ended. While troops were still returning home, active and retired military officers began lobbying to keep their chemical-weapons inventions. Fries, who led the Chemical Warfare Service through much of the 1920s, was determined to redeploy the technology for everyday uses like controlling crowds and criminals. He enlisted fellow military veterans, now working as lawyers and businessmen, to reach out to the press and help create a commercial market for the gases.

In the November 26, 1921 issue of the trade magazine Gas Age Record, technology writer Theo M. Knappen profiled Fries, who, he wrote, “has given much study to the question of the use of gas and smokes in dealing with mobs as well as with savages, and is firmly convinced that as soon as officers of the law and colonial administrators have familiarized themselves with gas as a means of maintaining order and power there will be such a diminution of violent social disorders and savage uprising as to amount to their disappearance.”

Knappen further explained to readers:

The tear gases appear to be admirably suited to the purpose of isolating the individual from the mob spirit … he is thrown into a condition in which he can think of nothing but relieving his own distress. Under such conditions an army disintegrates and a mob ceases to be; it becomes a blind stampede to get away from the source of torture.

The psychological impacts of tear gas gave police the ability to demoralize and disperse a crowd without firing live ammunition. Tear gas was also ephemeral and could evaporate from the scene without leaving traces of blood or bruises, making it appear better for police-public relations than crowd control through physical force. By the end of the 1920s, police departments in New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, San Francisco, and Chicago were all purchasing tear-gas supplies. Meanwhile, sales abroad included colonial territories in India, Panama, and Hawaii.

With this new demand for tear gas came new supply. Improved tear-gas cartridges replaced early explosive models that would often harm the police deploying them. Early innovators designed improved mechanisms for delivering tear gas, including pistols, grenades, candles, pens, and even billy clubs that doubled as toxic shooters. Tear gas soon became a weapon of choice for prison wardens, strike breakers, and even bankers. Tear gas-filled contraptions were fitted into vaults to stop robberies, and fastened onto the ceilings of prison mess halls to deter riots.

On July 29, 1932, in what Edgewood Arsenal, the U.S. military’s chemical research site, referred to in a memo as “a practical field test,” National Guard troops stormed the Washington, D.C. camps occupied by the “Bonus Army,” a group of veterans lobbying to receive their overdue wartime payments. During the forcible eviction that ensued, the troops fired tear gas into the encampment, engulfing it in smoke and fire. Two men were killed in the violence, and an infant child was said to have died of asphyxiation from inhaling tear gas. Though official reports of the incident claimed the baby died of natural causes, the Bonus Army only saw that denial as part of a government cover-up. The group’s ballad “No Undue Violence” mockingly testified:

“We used no undue violence”—

So, Baby Myers, be still!

Though it isn’t quite plain

To your little brain,

You were gassed with the best of will!

For the Bonus Army, tear gas became known as the “Hoover ration,” a further sign of growing economic disparity in America. But for police chiefs, business owners, and imperial consulates around the world, the eviction of the Bonus Army was a sign of the rapid damage and demoralization that tear gas could bring about.

Leading American tear-gas manufacturers, including the Lake Erie Chemical Company founded by World War I veteran Lieutenant Colonel Byron “Biff” Goss, became deeply embroiled in the repression of political struggles. Sales representatives buddied up with business owners and local police forces. They followed news headlines of labor disputes and traveled to high-conflict areas, selling their products domestically and to countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, and Cuba. A Senate subcommittee investigation into industrial-munitions sales found that between 1933 and 1937, more than $1.25 million (about $21 million today) worth of “tear and sickening gas” had been purchased in the U.S. “chiefly during or in anticipation of strikes.”

Prior to World War II, Italy used tear and other poison gases extensively in its war with Ethiopia, the Spanish used them in Morocco, and the Japanese used them against the Chinese. Although Western nations did not engage in chemical warfare during World War II, the use and development of tear gases became even more widespread afterward. In Vietnam, the U.S. fired tear gas into Viet Cong tunnels; the gas also landed in bomb-shelter dugouts, asphyxiating civilians trapped inside. In 1966, the Hungarian delegation to the UN, backed by other Eastern European nations, put the matter on the international agenda. “The hollow pretexts given for using riot-control gases in Viet-Nam,” the Hungarians argued, “had been rejected by world public opinion and by the international scientific community, including scholars in the United States itself.” Hungary called for the use of these chemical weapons in war to constitute an international crime.

Back in the United States, Vietnam War protesters faced tons of tear gas. In one of the largest deployments, California Governor Ronald Reagan ordered the National Guard to break up demonstrators in Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza in 1969. Helicopters carrying tear gas showered thousands of peacefully assembled students, as well as bystanders, including nursery-school children and swimmers in the university pool.

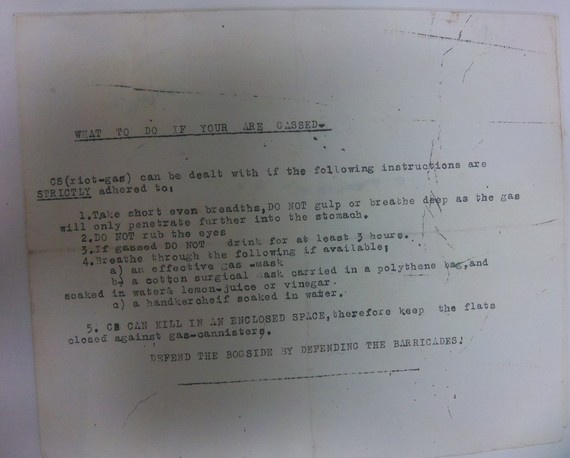

Meanwhile, France was busy expanding its use of new tear-gas formulas to quell student and worker uprisings that broke out in 1968. The French became so accustomed to facing tear gas that they trained residents in Derry, Northern Ireland to repel its effects during fighting in August 1969 between the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Catholic residents that came to be known as the Battle of the Bogside. This event marked the U.K.’s first civilian deployment of its new tear-gas formula—and brought the British military into Northern Ireland.

In the 1980s, human-rights groups increased their monitoring of the use of tear gas and riot-control techniques in zones of conflict or protest. South Korea came under increasing international pressure for its use of the chemical weapon against student protesters, as did Israel for deploying tear gas against Palestinians during the First Intifada. Between January 1987 and December 1988, the United States exported $6.5 million worth of tear-gas guns, grenades, launchers, and launching cartridges to Israel. Rights groups recorded up to 40 deaths resulting from tear gas during the First Intifada, as well as thousands of cases of illness.

Tear gas was once again transformed by the manufacture of handheld aerosol sprays beginning in the 1980s, when chemical-agents expert and inventor Kamran Loghman worked with the FBI to develop a weapons-grade aerosol pepper spray—an alternative, faster-acting form of tear gas designed to be more debilitating to the target. By 1991, Loghman’s invention was on the utility belts of police across the United States. Soon after, similar sprays were developed in the U.K. and France. It didn't take long before lawsuits arose, accusing police of harassment and, at times, torture. Between 1990 and 1995, more than 60 deaths linked to this “non-lethal technology” were reported in the United States.

Harking back to its large-scale use during Vietnam War protests, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, police forces deployed tear gas en masse against anti-globalization demonstrators in Seattle, Vancouver, Prague, and elsewhere. Though the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention again confirmed an international prohibition on the use of tear gases in warfare, it made an exception for their use in riot control by law-enforcement officials. Reporting on the Summit of the Americas in Quebec City in 2001, Saul Hudson wrote for Reuters, “Eye-stinging tear gas floated through the sealed-off zone in the historic city and entered venue building vents, reminding the presidents and prime ministers that violence marring major summits has become as predictable as their closing statements.”

During the Arab Spring, Occupy, and anti-austerity protests of 2011, tear gas once more made headlines. Mass shipments entered Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen, and Tunisia, largely from Combined Systems Inc. in the U.S. and Condor Nonlethal Technologies in Brazil, while tear gas was also deployed to break up protests in the U.S. and across Europe.

Ovrr the past two decades, sales of tear gas, and less-lethal weapons more broadly, have grown substantially. Just as tear-gas salesmen in the 1920s monitored news headlines, today’s chemical executives receive market reports informing them, for instance, that “civil unrest has become commonplace in many regions of the world, from protesters in Brazil to activists in the Middle East. Governments have responded by purchasing record amounts of non-lethal weapons.”

In the 100 years since it was first developed, tear gas, advertised as a harmless substance, has often proven fatal, asphyxiating children and adults, causing miscarriages, and injuring many. The human-rights organization Amnesty International has listed tear gas as part of the international trade in tools of torture, and Turkey’s medical association has condemned it.

Yet while tear gas remains banned from warfare under the Chemical Weapons Convention, its use in civilian policing grows. Tear gas remains as effective today at demoralizing and dispersing crowds as it was a century ago, turning the street from a place of protest into toxic chaos. It clogs the air, the one communication channel that even the most powerless can use to voice their grievances.

In this way, tear gas offers the police a cheap solution for social unrest. But rather than resolve tensions, it deepens them. This week in Ferguson, police fired tear gas into people’s backyards, set it off near children, and launched it directly at journalists. This treatment of a civilian neighborhood further damages the already highly fraught relationship between many Americans and those employed to “serve and protect” them. As those who signed declarations at The Hague back in 1899 knew, peace cannot be made through poison.