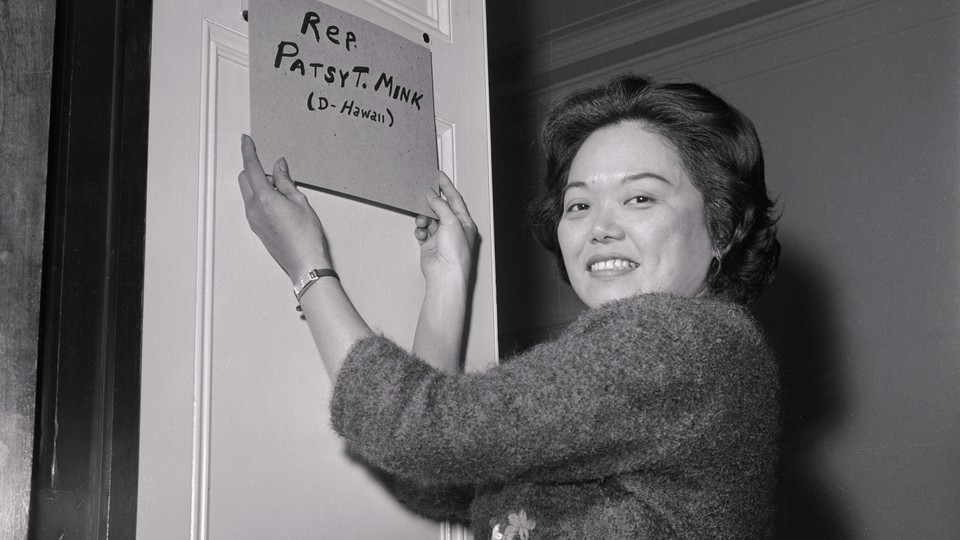

Patsy Takemoto Mink’s Trailblazing Testimony Against a Supreme Court Nominee

The first woman of color in Congress opposed G. Harrold Carswell’s nomination in 1970 and helped clear a path for Harry Blackmun, who wrote the Roe v. Wade opinion. It seems particularly relevant now.

On a winter Thursday morning in 1970, Patsy Takemoto Mink came before the Senate for its hearing on the Supreme Court nominee George Harrold Carswell.

The first witness to oppose Carswell’s nomination, Mink told the panel, “I am here to testify against his confirmation on the grounds that his appointment constitutes an affront to the women of America.”

Her testimony—which was followed by Betty Friedan, the author of The Feminine Mystique—would mark the beginning of a groundswell of opposition against Carswell, a southern judge and President Richard Nixon’s second attempt to appoint a Supreme Court justice (the first being Clement Haynsworth). As it happened, Nixon’s third nominee for the seat was Harry Blackmun, a midwestern Republican, who went on to write the Supreme Court’s majority opinion three years later in Roe v. Wade.

And so it seems appropriate, 16 years after Mink’s death, to look back on her role in opposing Carswell and on her trailblazing career, with Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination pending before the Senate and with it, quite possibly, the fate of Roe v. Wade. And there’s a twist to the Democratic opposition to Kavanaugh that brings Mink very much to mind.

Mink, the first nonwhite and Asian American woman elected to Congress in 1964, knew discrimination against women firsthand. A Japanese American Democratic representative from Hawaii, she was one of only about a dozen women serving in Congress at the time, and a rare female attorney. She had been admitted as one of two women in her class at the University of Chicago because the university had made a mistake, accepting her as a “foreign” student because she was from Hawaii, then a territory of the United States. After graduating, she opened her own law office in Honolulu because no law firms would hire her; they advised her to stay home with her young daughter instead.

Mink’s testimony was notable as it came about as the women’s movement was gaining steam in the late 1960s and 1970s. She brought to the forefront the inequality women faced in the workforce—something not taken seriously at the time. “It felt very momentous and risky,” recalled her daughter Gwendolyn Mink, then a 17-year-old, and now an independent scholar of U.S. social policy and politics. “Nobody had ever talked about sexism or misogyny for objecting to a Supreme Court justice.”

Mink’s argument before the Senate stemmed from a legal case that Carswell had presided over the year before. Ida Phillips had been denied a job on the assembly line of Martin Marietta Corporation because she was the mother of preschool-aged children. No such rule, of course, applied to fathers of preschool-aged children. The lawsuit had made its way to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Carswell, one of the judges, had refused to hear the case.

“Judge Carswell demonstrated a total lack of understanding of the concept of equality,” Mink said in her testimony. “His vote represented a vote against the right of women to be treated equally and fairly under the law.”

Her statement was challenged by Senator Marlow Cook, a Republican from Kentucky, who pointed out that Carswell was not the only judge to decline to review the case. “As the father of four daughters and knowing how my household is completely controlled by women, I am very much in sympathy with the remarks that you have made,” he began. But, he continued, “are you aware of the fact that 10 other judges on the Fifth Circuit did not allow a hearing?”

Mink responded in her distinct, forthright manner. “Yes, I am well aware of that, Mr. Senator,” she said. “But the other nine are not up for appointment to the Supreme Court.”

Her testimony against Carswell was not the first—nor would it be the last—time that she drew attention to the unfair treatment of women in the United States.

Throughout her trailblazing career—which included two tours and 12 terms in Congress from 1965 to 1977 and 1991 to 2002—Mink was a steadfast advocate for women. Among her most well-known endeavors, she co-authored and championed Title IX, a law aimed at ending gender discrimination in higher education that was signed into law by Nixon in 1972. Upon Mink’s death in 2002, it was renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act.

Mink also pushed for legislation to support better child care and early-childhood education, as well as for millions of dollars in funding so that schools could train teachers, update textbooks and curricula, and offer programs to make education more equitable for girls.

As the first woman of color elected to Congress, Mink also supported the Civil Rights movement. In her first act in Congress, she joined the protest against Mississippi’s suppression of black voters. Later, she also spoke out against the treatment of Wen Ho Lee, the Taiwanese American scientist arrested because of his race for espionage in 1999 and later exonerated.

She was also a fierce advocate for her home state of Hawaii and the Pacific Islands. She fought against nuclear testing in the Pacific, and she helped establish the Pu’ukoholā Heiau National Historic Site in Hawaii, a cherished landmark for Native Hawaiians.

But she wasn’t always popular. She was criticized and called “Patsy Pink” for her opposition to the Vietnam War. She briefly ran for president on an anti-war platform in 1972, garnering only a handful of votes. She was sometimes at odds with her own Democratic Party; its leaders did not always back her campaigns, and sought to undermine her.

“She was willing to buck the party leadership. She was independently minded,” said Troy Andrade, a University of Hawaii law professor who led the effort for Mink to be posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014. “If she saw something that was wrong, she was going to push until it was corrected.”

Andrade referenced one of Mink’s quotes, which became the title for the Patsy Mink documentary Ahead of the Majority: “It is easy enough to vote right and be consistently with the majority. But it is more often more important to be ahead of the majority, and this means being willing to cut the first furrow in the ground and stand alone for a while if necessary.”

Mink was born in Maui in 1927. Decades earlier, her grandparents had been among those recruited from Japan to work in the sugarcane fields of Hawaii. Her mother was one of 11 siblings. Her father, who was orphaned at a young age, was one of the first Japanese American civil-engineering graduates at the University of Hawaii, and became a land surveyor for the sugar plantation. Growing up, she saw the stark segregation between Asians and Native Hawaiians and their white bosses on the plantation.

The day after her 14th birthday, Pearl Harbor was attacked. Though Japanese Americans in Hawaii were not interned like those on the West Coast, they were still under scrutiny. One night, Mink’s father was taken away for questioning (and later released), an experience that rocked the family and left a deep impression on Mink about the challenges of the law.

As a child, Mink wanted to be a doctor. She took many of the steps that she thought would lead her there: She was the valedictorian and the first female class president at Maui High School; she was also elected as president of the Pre-medical Students Club in college.

But in 1948, she sent dozens of applications to medical schools, and wasn’t accepted to a single one. That experience—along with later seeing her daughter face similar pushback for being a girl—inspired her fight on behalf of women. “Her personal experience with gender discrimination fueled her desire to make sure other people didn’t have that experience,” said Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, the chair of Asian American Studies at UC Irvine, who is writing a biography of Mink with her daughter.

Incidentally, while Title IX is well known for propelling the rise of women in sports, it also opened the doors for women to attend medical school. Last year, for the first time, the number of women enrolling in medical school surpassed the number of men, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges—one of the lasting results of Title IX.

“I certainly consider Title IX one of my most significant accomplishments while I served in Congress from 1965 to 1977,” Mink said on the 25th anniversary of Title IX. “The pursuit of Title IX and its enforcement has been a personal crusade for me. Equal educational opportunities for women and girls is essential for us to achieve parity in all aspects of our society.”

In 1976, Mink was defeated in her race for a Senate seat. Returning to Hawaii, she served on the Honolulu City Council and made a failed bid for governor of Hawaii. In 1990, she ran and won back her seat in Congress.

Back in Washington, D.C., another Supreme Court candidate was about to be appointed: Clarence Thomas. Nominated by President George H. W. Bush in 1991, Thomas’s approval had been all but assured until news broke about Anita Hill, an attorney who served under Thomas and who had accused him of sexual harassment.

Once again, Mink would seek to derail the nomination. And this time, she would not be the lone congresswoman speaking out. When the Senate Judiciary Committee refused to let Hill testify, Mink and six other Democratic congresswomen, including Barbara Boxer of California, Patricia Schroeder of Colorado, and Louise Slaughter of upstate New York, made a spontaneous decision to march together to the Capitol room to demand a meeting. Their climb up the stairs was memorialized in a front-page New York Times photograph, a moment that is now considered a turning point for women in politics. But though the Senate committee ultimately allowed Hill to testify, Thomas was approved in a narrow 52–48 vote.

Mink was much more successful in her opposition to Carswell in 1970. Momentum was building against his nomination: Reports and testimony came out showing he held not only potentially sexist views, but also racist ones, including his part in helping a golf club stay whites-only for as long as possible. A movement by a group of law professors pointed out his poor case record. Carswell was called an incompetent judge, one who was “mediocre” at best. Two months later, the Senate—including several Republicans such as Senator Cook of Kentucky, who had initially defended Carswell during Mink’s testimony—voted to reject him, clearing the way for Harry Blackmun.

He wrote the high court’s majority opinion in Roe v. Wade, legalizing abortion, three years later.

Today, with Roe v. Wade potentially on the line if Kavanaugh’s nomination is approved and he votes to overturn the decision, Democrats are doing everything they can to block him. One of them is Senator Mazie Hirono of Hawaii, a friend of Mink, who questioned Kavanaugh’s opposition to Native Hawaiians as a protected group during last week’s hearing. That issue could also influence the swing vote of Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska; Alaska Natives are worried that Kavanaugh could impact their fishing rights. But will their efforts be enough?

None could describe the stakes any better than Mink did in her testimony against Carswell before the Senate Judiciary Committee. “The Supreme Court is the final guardian of our human rights,” she said. “We must rely totally upon its membership to sustain the basic values of our society.”