Dave Chappelle Doesn’t Think America Is Saved

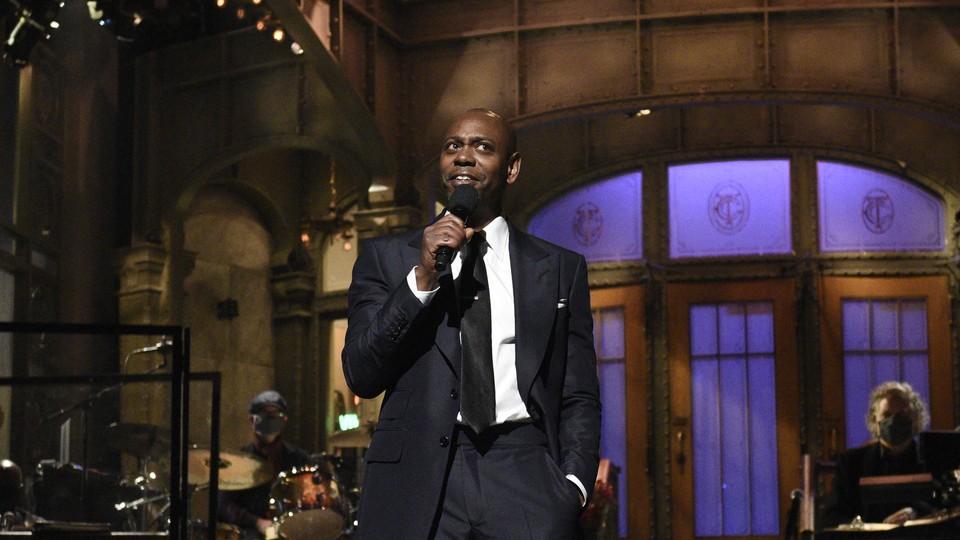

After four years, the comedian returned to host Saturday Night Live. In 16 minutes, he explained why a new president alone won’t fix the country.

Dave Chappelle had the same thing on his mind when he came out onto the Saturday Night Live stage in 2016 and 2020, both times hosting the show right after the U.S. presidential election. “Don’t forget all the things that are going on … all these shootings in the last year,” he said in 2016, invoking the massacre at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub. Last night, Chappelle tried to strike a more optimistic tone as he took drags from a cigarette in front of a mask-wearing studio audience. “You guys remember what life was like before COVID? I do! There was a mass shooting every week, remember that? Thank god for COVID; someone had to lock these murderous whites up and keep them in the house,” he joked.

After each election involving Donald Trump, SNL has invited Chappelle to host, treating him like a moderator for our greater national reckoning, a comedian seasoned and blunt enough to broach sensitive matters of importance. Both times, he’s opened his set by pointing out that much ails America beyond the contentious election it just endured. His monologue on last night’s episode took plenty of jabs at Trump and his administration’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic. But the thrust of Chappelle’s comedy was wider and darker. He urged the audience to consider the grievances of millions of voters feeling abandoned or adrift in their own country, connecting those feelings to the lived experiences of generations of Black Americans. Chappelle barely mentioned President-elect Joe Biden at all. Instead, he built to an argument that no president can save America if Americans don’t want to save one another.

Chappelle’s consistency in both his SNL monologues is all the more striking because the two episodes around them are so different. In 2016, after Trump’s victory, a mournful pall hung over the show. Kate McKinnon tearfully sang “Hallelujah” in costume as Hillary Clinton, a bizarre spectacle that reflected the shell shock of the show’s writers and actors following Clinton’s loss. In 2020, the show winked at the strange self-seriousness of that earlier moment by having Alec Baldwin as Trump sit down at a piano to perform a somber version of the Village People’s “Macho Man.” The rest of the episode was filled with typically upbeat, ridiculous material; on “Weekend Update,” the co-anchor Michael Che sipped a celebratory drink while reading his jokes.

Chappelle displayed more equanimity (indeed, that was the title of his 2017 Netflix comedy special, in which he charged at many a social taboo with varying levels of success). Using the kind of profanity that only a comedian of his stature can really get away with on NBC, he spoke of Yellow Springs, Ohio, the small town he lives in, and the economic depression in the area. “People make more money from their stimulus checks than they do if they work. So a lot of people don’t want to work. You know what that reminded me of? Ronald Reagan!” Chappelle said. “What did Ronald Reagan say about Black people, how we’re welfare people, drug addicts? Who does that sound like now?”

He kept returning to that idea—that the rural and working-class white voters who have shifted to the Republican Party in the age of Trump can be easily stereotyped, just as Black people have been throughout America’s history. “Don’t even wanna wear your mask cause it’s oppressive? Try to wear the mask I’ve been wearing all these years! I can’t even tell something true unless it has a punch line behind it,” he continued, ruefully. “You guys aren’t ready; you aren’t ready for this. You don’t know how to survive yourselves. Black people, we’re the only ones that know how to survive this.”

There’s a sharpness to that sentiment, and undeniable bitterness—Chappelle is essentially noting that, unlike Black Americans, so many white Americans still don’t truly understand how thoughtlessly their government treats them. But Chappelle’s comedy also has a blunt sort of compassion to it; to him, America won’t be healed by an election, but by people coming to some deeper understanding. “I would implore everybody who’s celebrating today to remember it’s good to be a humble winner. Remember when I was here four years ago? Remember how bad that felt? Remember half the country right now still feels that way,” he said.

Indeed, four years ago, Chappelle ended his set by extending an olive branch. “I’m wishing Donald Trump luck,” he said. “I’m going to give him a chance, and we the historically disenfranchised demand that he give us one too.” In 2020, after laying bare the racism that drove many white people to support Trump, Chappelle tried to understand how those voters might feel similarly ignored by their own country. “For the first time in the history of America, the life expectancy of white people is dropping, because of heroin, because of suicide. All these white people out there that feel that anguish, that pain, they’re mad because they think nobody cares,” he said. “Let me tell you something: I know how that feels.”

Some viewers might resent Chappelle’s attempt to arouse sympathy for voters who found community by celebrating the suffering of others, as my colleague Adam Serwer memorably wrote. The issues facing America are always going to be more complicated than they sound in a 15-minute stand-up-comedy set. Gun violence, sadly, has not disappeared in 2020, even if there hasn’t been an incident of mass murder on the scale of Orlando or Las Vegas. Trump’s base in 2020 was not just rural white voters—he in fact expanded his appeal to people of color around the country. But Chappelle’s point was less about statistics than the painful feeling that much of your country hates you, which can transcend race or class. The antidote he offered at the end of his 16 minutes was for Americans to learn to hate that feeling rather than one another. That feeling is “what I fight through; that’s what I suggest you fight through,” he said. “You gotta find a way to forgive each other. Gotta find joy in your existence in spite of that feeling.”