The Shockingly Familiar Killing of Walter Scott

Black men are disproportionately likely to be pulled over in North Charleston. Americans are killed by police far more than citizens of other countries. But officers seldom face charges.

Walter Scott's killing is unusual in several ways. It's unusual that a traffic stop ended in death. It's unusual—and decisive—that it was caught on film. And it's highly unusual that it has produced a murder charge against the officer.

But in other ways, the incident seems depressingly familiar. Scott was stopped for having a tail light out, the sort of minimal issue that advocates say is often used as a pretext to harass black citizens and to search for other violations. As The New York Times noted, the population of North Charleston, where Scott was shot, is 47 percent black and 37 percent white. (Michael Slager, the officer who shot Scott, is white—along with 80 percent of the city's police department, according to the most recent available figures.)

South Carolina requires police departments to track all traffic stops that don't end in a citation or an arrest, which produces a useful if incomplete picture of how many stops might be essentially pretextual. Of more than 22,000 stops in 2014 in North Charleston, 16,730 involved African Americans—almost 76 percent of stops, much higher than the city's black population. Most of those, some 10,600, involved black men, like Scott.

An encounter with the police is generally stressful. It's especially difficult when black citizens are wary of the police and feel unfairly targeted. African American residents of North Charleston have been complaining about mistreatment by police for years. The Charleston Post and Courier reported on complaints in 2010; the-then chief of police replied by arguing that the ends justified the means. "I am not going to apologize for the strategies we've employed in these areas," he said. "Those strategies are working and the violence is dropping dramatically." Two-thirds of stops that failed to produce a ticket or arrest involved black drivers. The following year, however, the chief insisted his department did not profile.

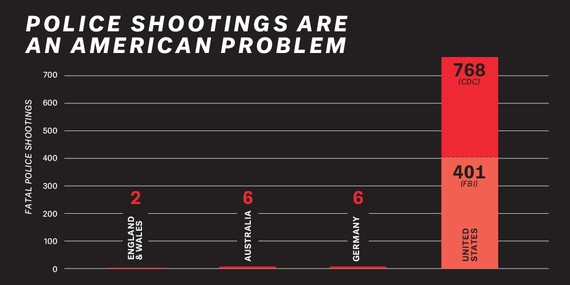

Most encounters do not end with violence or death, even if they produce humiliation and tension with police. But they are far more likely to end in a killing in the United States than anywhere else. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, police shot and killed 828 people in 2011, a figure that includes all killings, justifiable or not. By comparison, during the same year, there were two fatal police shootings in England and Wales; six in Australia; and six in Germany.

When an incident does turn fatal, the police officer's version of events often proves difficult to contest. An anonymous bystander's video, though, made the Scott case different. Slager's report said that Scott had taken his Taser and that the officer felt threatened. But the video revealed that Scott had been running away from Slager when he fired eight shots into his back. It also showed Slager picking something up and then dropping it near Scott's body—perhaps the Taser. The footage changed it from another disputed tragedy into a murder case.

"I thought that my brother was gunned down like an animal," Anthony Scott, the victim's brother, said. "It was just unbelievable to me to see that."

Yet the family said they thought it was important that the video was shown. So powerful was the video, that when Slager's attorney finally saw it, he immediately dropped him as a client. Video has had an equally potent impact in other cases of police violence—including the shooting of a driver by a South Carolina state trooper last year.

Technology has made it more common for such shootings to be filmed, since many people now carry a video camera in their pocket as a matter of course. A good example came in the Los Angeles Police Department shooting of a homeless man on Skid Row in December, which was captured by both bystanders and surveillance cameras, from several angles. But as my colleague Robinson Meyer writes today, capturing these images also requires impressive courage. Whether officers have reason to shoot or not, the videos prove clarifying, whether they bear out an officer's account or call it into question. Even when police are wearing body cams—as lawmakers are demanding now—third-person footage is a useful and sometimes essential supplement.

In addition to being charged with murder, Slager was fired by the city of North Charleston on Wednesday. If he's convicted, Slager could face the death penalty. That makes this case exceptional. As a grand jury's decision not to charge New York police officer Daniel Pantaleo in the death of Eric Garner vividly demonstrated, officers are seldom charged with crimes when suspects or citizens are killed. A Bowling Green State University report found 41 murder or manslaughter charges for police involved in on-duty shootings over a seven-year period—a stretch during which the FBI counted 2,718 cases of justifiable homicide by law-enforcement officers. Meanwhile, a separate Cato Institution report found that only one in three officers who are charged are convicted.

That makes it all the more surprising that Slager wasn't the only officer charged in South Carolina on Tuesday. Justin Gregory Craven, an officer in North Augusta, was arrested and charged in the death of Ernest Satterwhite, whom Craven shot repeatedly after a car chase that ended in Satterwhite's driveway. That shooting, too, was caught on video.

The growing ubiquity of smartphone cameras hasn't come close to stopping law-enforcement homicides—in fact, the total grew from 2003 to 2011. But the availability of film is starting to change what happens in their aftermath.