The City That Believed in Desegregation

Integration isn't easy, but Louisville, Kentucky, has decided that it's worth it.

Hawthorne Elementary in Louisville, Kentucky, looks like what you might imagine a typical American suburban elementary school to be, with students’ art projects displayed in the hallways and brightly colored rugs and kid-sized tables and chairs in the classrooms. It’s located in a predominantly white neighborhood. But the students look different than those in many suburban schools across America. Some have dark skin, others wear headscarves, others are blonde and blue-eyed. While many of them qualify for free and reduced lunches, others bring handmade lunches in fancy thermal bags and come from well-off families.

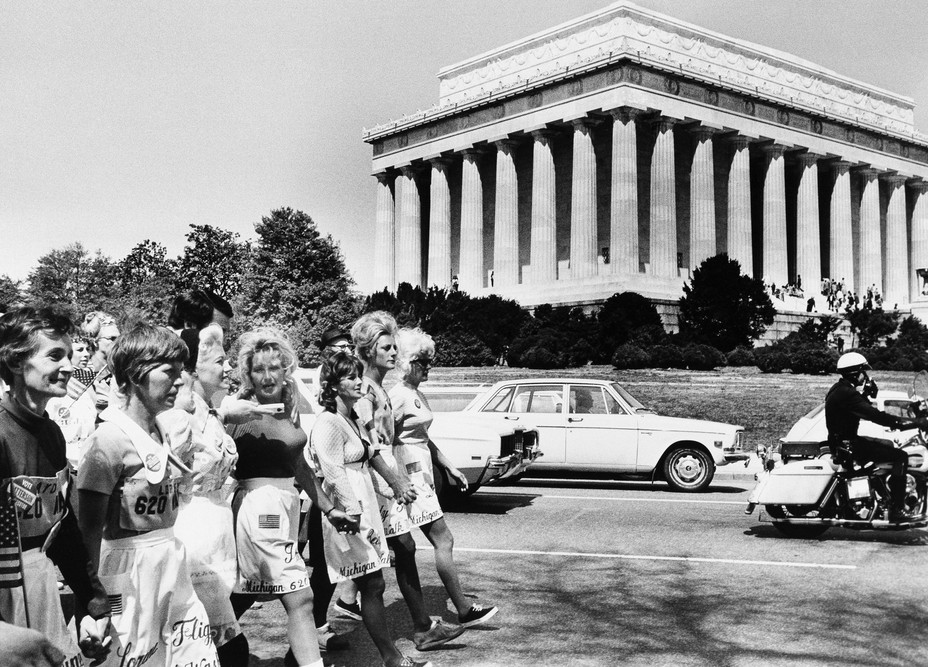

Ever since a court forced them to integrate in the 1970s, the city of Louisville and surrounding Jefferson County have tried to maintain diverse schools. Though the region fought the integration at first, many residents and leaders came around to the idea, and even defended it all the way up to the Supreme Court in 2006.

“Because the Metro area has a countywide system of public schools that are truly unitary,” the district argued in that case, Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education, “it has avoided much of the race-based strife and race-conscious decisions that characterize other metropolitan areas with highly segregated schools.”

The Supreme Court decided against Jefferson County, ruling in favor of a parent who argued that her son’s bus ride was too long. But in the years since, the district has found other creative ways of keeping its schools diverse. Today, the Louisville area is one of the few regions in the country that still buses students among urban and suburban neighborhoods. Jefferson County Public Schools is 49 percent white, 37 percent black, and 14 percent Latino and other ethnic and racial groups.

The county, which borders Indiana on the south, spreads across 400 square miles and encompasses census tracts in which more than half of the population lives below the poverty level, and tracts in which less than 10 percent does. But there are no struggling inner-city schools here—the city and county schools are under the same district, and the most sought-after high school within it, duPont Manual, is located near downtown.

Indeed, it could be argued that Louisville, an economically vibrant city in a highly conservative and segregated state, is a success today in large part because of its integrated schools and the collaborations among racial and economic groups that have come as a result. “Our PTA president will drive downtown into neighborhoods she probably would not have gone to, to pick up kids to bring to her house for sleepovers,” said Jessica Rosenthal, the principal at Hawthorne Elementary. “I just don’t know how likely that is to happen in a normal school setting.”

In contrast, regions that kept city and suburban schools apart have been plagued by growing inner-city crime, low academic achievement levels for black children who live in the city, and a hollowing out of the city by middle-class families who feel that they need to move to the suburbs to ensure their children will get a better education.

The clearest example is Detroit, which faced a court order very similar to Louisville’s in 1972. But in 1974, Detroit was released from combining city and county schools by Milliken v. Bradley, a Supreme Court decision many academics consider one of the worst in the Court’s history.

“Go to Louisville, go to Detroit they’re just different planets today.”

In 1972, the proposed integration districts in both Detroit and Louisville had populations that were roughly 20 percent black and 80 percent white. At the time, both regions’ schools were equally segregated, according to Myron Orfield, the director of the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity at the University of Minnesota, who recently published a paper comparing the two cities and their school desegregation policies. By 2000, though, the average black Detroit student went to school with less than two percent white students, while in Louisville, the average black student went to a school that was half white. In 2011, 62 percent of Louisville fourth-grade students scored at or above basic levels for math; only 31 percent of Detroit students did, Orfield found.

“Go to Louisville, go to Detroit they’re just different planets today,” Orfield told me. “These are places that had the same percentages of black people, they had the same percentage of poor people, they were almost identical, racially and socially. And Louisville’s thriving, and it wasn’t. And Detroit’s collapsed.”

The city of Detroit has for years been struggling with a declining tax base, high vacancy rates, and high crime, while its suburbs are some of the whitest and wealthiest areas in the state. Louisville, by contrast, has largely embraced the idea that a region can’t prosper if some of it is mired in poverty. Partly because of the success of the city-county school merger, the city of Louisville combined its government with Jefferson County’s in 2003, sharing tax revenues and resources throughout the area, now called Louisville Metro. There are still areas of concentrated poverty in Louisville, but unlike Detroit, where the suburban areas have largely washed their hands of the city’s troubles, the Louisville Metro area is still—at least on paper—devoted to the welfare of the whole region.

“We do try to look at this as—the county cannot be successful if areas that large are not prospering along with the rest of the county,” said James Reddish, of Greater Louisville Inc., which is the Chamber of Commerce for the region. “Prosperity in one part of the county feeds into the same city-county government as where there is lack of prosperity in another.”

The idea of metropolitan-wide school districts made a lot of sense in the 1960s, when a racially-segregated America required a host of court decisions including Brown v. Board of Education in order to stop segregating students in separate but “inherently unequal” schools.

In Detroit, the school population had gone from 45 percent black in 1961 to 72 percent black in 1972, according to Orfield, the Minnesota professor. Without the white-suburban schools, it wasn’t really possible to make Detroit schools more racially integrated, so in 1972, a district court ordered the region to created a school plan that would bring together 53 suburbs and the city of Detroit in order to achieve racial integration. The order was met with fury in Detroit, where the Klu Klux Klan blew up 10 school buses in a suburb so they wouldn’t be used to integrate the schools. The judge who had ordered busing of students between the suburbs and the city received death threats, and eventually had two heart attacks and died before the case was argued before the Supreme Court.

Parents and community leaders in the suburbs fought the plan vociferously, and when the case reached the Supreme Court, in 1974, the majority called the integration plan “wholly impermissible.” In its Milliken decision, the Court threw out the idea that suburban districts in the Detroit area had to be part of the city school district. The suburbs had not participated in discrimination, Justice Burger wrote in his opinion, and should not be punished. Desegregation does not require “any particular racial balance in each ‘school, grade or classroom,’” he wrote.

The decision led to even more segregation in Detroit, as white families continued to move to the suburbs, in large part to put their kids in the schools there, bringing with them tax revenue and businesses. By 2006, the city of Detroit’s public schools were 91 percent black and 3 percent white, while the schools in the district of Grosse Pointe, which borders Detroit, were about 89 percent white and 8 percent black.

“One of the reasons white people leave central cities is because schools become segregated before neighborhoods do,” Orfield said. “White families stop buying in certain areas where the schools become all poor and non-white.”

Now the city of Detroit is 83 percent black, while Oakland County, north of the city, is 78 percent white, and is the richest county in the state. In Detroit, 39 percent of people were below the poverty line in 2009-2013, according to Census data, while just 10 percent of Oakland County was.

Detroit wasn’t the only place that successfully fought a metropolitan-wide school integration plan. Richmond, Virginia, avoided a similar plan in the 1970s, leading to widespread segregation in county and city schools. In fact, a number of cities in the north and east have avoided metropolitan-wide plans and created a system of mostly black city public schools and white suburban public schools, according to Erika Frankenberg, a Penn State professor who studies the issue.

This is what makes Louisville so unusual. Even after the Milliken decision, a panel in December of 1974 ordered the integration of the city and county schools to continue in the region. Beginning in 1975, students were sorted alphabetically and bused to different schools around the county. Under the order, schools in the county had to be between 15 and 50 percent black.

The Louisville plan wasn’t popular at first. Thousands of protesters rallied against busing at the district’s schools, protesting and vandalizing police cars until the governor called in the Kentucky National Guard to supervise buses for the first few days.

But something strange happened as the integration plan continued. Many of the residents' fears failed to materialize, and after a few years the protests ceased.

It’s as though “people are amazed to discover that people from another race or ethnic group are actually pretty similar to them,” said Gary Orfield, the co-director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, who has worked with the city for decades on the plan (and is Myron Orfield’s brother). “There’s a tremendous deflation of protests when almost all the stereotypes people hold aren’t true.”

Orfield remembers the vitriol in Louisville in 1975, when the unions and white population alike vehemently protested the court order—at one point, a bishop supportive of the integration was spat on as he came out of church. But Orfield also remembers how, five years after the plan began and the judge ceased active supervision of the court order, the region’s leaders “decided what he had done was a good idea and they had a banquet for him.” Not everyone felt this way—Jefferson County saw a drop-off in enrollment after the integration, but it later leveled off.

Much has changed in the decades since the bussing plan began. Surveys done back in the 1970s indicated that 98 percent of suburban residents opposed the plan. But in a 2011 survey, 89 percent of parents in Jefferson County said they thought that the school district’s guidelines should “ensure that students learn with students from different races and economic backgrounds.” About 87 percent of parents asked said they were satisfied with the quality of their child’s education.

By 2006, after a frustrated parent fought the busing plan all the way to the Supreme Court, many in Louisville preferred integration to the alternative. The case was named for Crystal Meredith, who had moved to Louisville in 2002 and was required to send her son to a school 10 miles away since the school near her home was full. She and other parents argued that the plan violated their children’s Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection under the law. Their case was merged with Parents Involved, a similar case from Seattle.

When a bitterly divided Supreme Court struck down Jefferson County’s integration plan, students and parents spoke openly about how they disagreed with the decision. One graduate of Jefferson County Public Schools wrote an impassioned op-ed in the local paper, suggesting that among those who opposed integration, there was “no talk of society as a collective group, no concern for others, no consideration of communal benefit.” He recounted an experience he'd had at college in Virginia, where peers chanted racist slogans and carried around Confederate flags during an “Old South” fraternity party—a display that horrified him, he said, in part because he had been exposed to diversity in Louisville.

In a sign of how much the region had changed since the 1970s, the district pledged to maintain its commitment to diversity even after the Supreme Court ruling. “This community really values an integrated school system. It is a core value within Jefferson County,” superintendent Sheldon Berman told the Louisville Courier-Journal in reaction to the decision. “We will find some creative ways to continue to model that.”

Their initial plan used household income and a complex busing system to try and integrate students, but it confused parents and was not very effective. So Jefferson County brought in Gary Orfield and asked him to help design a plan that would follow the law but still keep the district’s schools diverse.

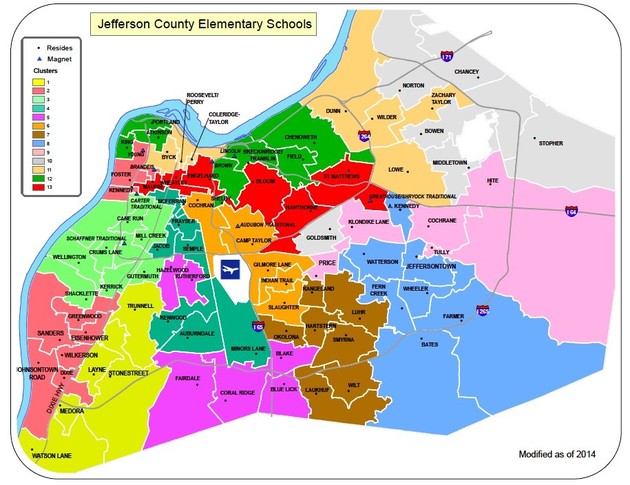

Currently, the district puts schools in “clusters,” which are groups of diverse neighborhoods. Parents fill out an application listing their preferences for certain schools in the cluster, and the district assigns students to certain schools in order to achieve diversity goals. It does this by ranking census blocks on a number of factors, including the percentage minority residents, the educational attainment of adults, and household income, and mixing up students from various blocks. Parents can appeal the school assignments, but have no guarantee of getting their top choice. They can also apply for magnet schools and special programs such as Spanish-language immersion.

Parents who went through Jefferson County Public Schools themselves tend to especially appreciate the system’s diversity. Jessica Goldstein was a first grader in 1977, and vaguely remembers crowds of people standing around the school on her first few days in protest. Goldstein, who is white, says some of her friends avoided being bused by filing for medical exemptions, saying allergies, headaches, and other health concerns would make busing a hardship. But Goldstein was bused, starting in middle school, to a school in Louisville’s predominantly black West End.

“I remember very clearly my mother telling me that I shouldn’t even think about trying to get out of it,” she told me. “That she went to school when they were completely segregated by race and that it was wrong. No complaining, no nagging, no asking questions and I was going to get on the bus and I was going to go.”

Goldstein actually liked the school in the black neighborhood more than the one she’d been attending in her predominantly white neighborhood. She filed a petition to continue to attend that school (this was needed since, at the time, white students were only bused for two of their first 12 years of schooling, in contrast with black students were bused for up to 10) and it was granted. “I think it was very beneficial to go to school and to be friends with and spend your day with people whose economic conditions and life stories are very different from yours,” Goldstein reflected. “It instilled an attitude of gratitude; it helped build some perspective.”

In fact, over the years, studies have shown that students who attended the integrated schools in Jefferson County were better prepared to work with people from different racial or ethnic backgrounds and held fewer stereotypes than those who did not attend integrated schools.

“One of the reasons white people leave central cities is because schools become segregated before neighborhoods do.”

City-county school integration also reduced white flight from the city of Louisville, keeping home values and tax revenues stable, says Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, who conducted a study comparing housing segregation in four cities that had different school-integration policies.

When parents decide to buy a home, they often make choices based on neighborhood schools. This has an effect on home prices: One Connecticut study found that buyers were willing to pay $7,468 more for a house near a less diverse school. But parents in Louisville know that whether they buy a house in the city or the suburbs, their child will go to a school that has similar resources—and racial breakdown—as other schools in the district.

“When families are thinking about moving around the metro area, they know that any neighborhood is going to be linked to a school with a racial composition that reflects the broader-metropolitan area,” she said. “It helps disentangle the school-housing relationship.”

In fact, the rate of segregation in Louisville’s housing declined more quickly than in other cities after the school-integration plan, falling more than 20 percent between 1990 and 2010. That rate of the decline in housing segregation was double that of the Richmond area, which had avoided city-county school integration.

“This central finding suggests that, in some ways, school policy can become housing policy,” Siegel-Hawley concluded, in the study.

It helped that Louisville was also one of the few metropolitan areas that made a concerted effort to integrate housing as it integrated the schools, Siegel-Hawley said. Some African American families received vouchers to move to white areas of town and were exempt from busing. Neighborhoods that were racially balanced would sometimes be exempted from busing. One human rights group even posted billboards around town that read “Fight Forced Busing, Support Fair Housing” to remind people that more integrated neighborhood would mean fewer bus rides for students.

The city-county school integration has also led to a more-solid tax base in Louisville, since families aren’t leaving the city. Louisville’s tax base was 122 percent of the regional average in 2008, Orfield said, and its bond rating was Aa2, or high quality, in 2010. In Detroit, where residents fled to the suburbs in part because of schools, the tax base was 28 percent of the regional average and in 2012 its bond rating was junk status, Orfield found.

According to census analysis by William H. Frey, a Brookings demographer, Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis are three of the most segregated regions of the country, with dissimilarity indices of 75.3, 74.1, and 72.3 respectively (0 is complete integration, 100 is total segregation). Louisville/Jefferson County is the 43rd most segregated region in the nation, but it's been improving, with its dissimilarity index falling 10 points between 1990 and 2000, and 5.7 more points between 2000 and 2010, to 58.1.

Louisville's busing plan also led to higher achievement for low-income students, which helped provide qualified workers to the metropolitan area. The Chamber of Commerce for the Louisville area testified in the 2006 case in support of the busing plan, saying as Gary Orfield summed it up, that Louisville “was a city, unlike other places, where you could hire people from any school and they would actually be educated, and they would know how to work with others.”

Louisville is outpacing the nation in some employment growth metrics, according to a 2013 report by the St. Louis Fed. It's possible that a continued commitment to school integration played a part in that, by giving a good education to students who might otherwise have been exposed to failing schools and high teacher turnover.

“The basic idea is that a school system that educates all kids well is a really good entrance to the economy,” said Siegel-Hawley. “And deters things that might detract for the health of a region like crime, dropout rates, things like that.”

Of course, there are studies showing the benefits of an integrated city-county school system and then there’s the reality on the ground. It sounds like a good idea to bus students to make opportunities equal, but equalizing opportunity for all has real costs for some.

When I was speaking with Helene Kramer, the school-district spokeswoman, about how students are assigned to schools now, she mentioned offhand that the office in charge of student assignment looked like a bunker. She was right. The Lam Building, which houses the Parent Assistance Center, is a giant concrete structure with no windows that looks like it could withstand riots of parents protesting about the child their school has been assigned to attend.

While there, I ran into Kia Venerable, who was new to Louisville and was trying to enroll her three children in school. The ones they’d been assigned to were far from her neighborhood, and her high-school aged son, who had moved to town a few months earlier, had to get up at 5:30 in order to catch the right bus.

“It could be in Egypt, as far as I’m concerned,” she told me. “It’s like 1,000 miles away and that’s ridiculous.”

Well-off parents moving to Louisville say their friends often advise them to buy a house in nearby Oldham County, Kentucky, or in the Indiana suburbs to the north of the city to avoid busing. When one woman posted to Yelp that she was moving to Louisville from Charlotte, North Carolina, and wanted to know which area had the best schools, the responses were blunt.

“The schools in Jefferson Co are in fact good its the whole school assignment plan that stinks. You can move next door to the school you want your child to enroll in but there is NO guarantee that your child will get in,” one woman wrote in response. “Look outside the county to avoid this mess unless you want to go private.”

Indeed, many white families have pulled their children from Jefferson County Public Schools. The Archdiocese of Louisville has 35 elementary schools serving 13,755 students, and the percentage of Catholic students enrolled in those schools is the third highest in the country, 7.3 percent, compared to a national average of 2.3 percent.

Jenneh Bradshaw moved to Indiana to escape the Jefferson County Public Schools. When her daughter was in elementary school, she lived on the same block as an elementary school, Roberta Tully Elementary, but was bused to Engleheard Elementary, a downtown school with low test scores. It could take up to an hour to get to school in rush-hour traffic. Her daughter would leave at 6:30 in the morning, sometimes not get home until 4:30, and refused to stay after school for any activities because it took so long to get home afterwards.

Bradshaw appealed the decision but was denied. Most frustrating, perhaps, was that she met a fellow parent who lived a block from Engleheard and was trying to transfer from Tully but was also denied. They asked the school district if their children could just switch places, but since one student was white and the other was black, the district refused.

Bradshaw eventually pulled her daughter out of public school and enrolled her in an online charter school. Her daughter didn’t like that, but Bradshaw, who is a single mother, decided she couldn’t fight the Jefferson County school system anymore, and moved to Oldham County.

“If you have a kid with any kind of special needs—even something as simple as dyslexia—forget about it,” she said, about Jefferson County Public Schools.

Bradshaw argues that low-income parents, or those without a lot of resources are disadvantaged in the Jefferson County system because they can't fight the school district, but even those parents with resources find the process aggravating. When Scott Weddle and his wife started to look at public schools for their son Wyatt, friends told them that if they showed up at PTA meetings, and continued to nag the school of their choice, they’d get their son in to whatever school they wanted.

They did their research and chose a high-ranking school in their cluster, but their son was assigned to the lowest-ranked one. They appealed again and again, writing letters and pleading to be reassigned to the school they wanted, the one where most of their friends’ children went.

“We had friends that said they had sent seven, eight, nine, 10 appeals; they told us not to give up,” he told me. “But we got into a situation where we felt like we were banging our head against the wall, and they were saying we had no choice but to send him to the lowest-performing school in cluster.”

Finally, the Weddles applied for a transfer to a different school in the district, and their son was accepted into that one. They’re actually very happy with the school he now attends, and are glad they didn’t spend money on private school, which they had considered. But, Weddle said, his son’s class only has a handful of minority students, so it almost seems like the process didn’t do what it was supposed to.

And, he said, “we’re already starting to look down the road to middle and high school,” though his son is only in kindergarten.

Headaches such as these have led many districts around the country to dismantle their integration plans, even before the Meredith decision. In 1991, the Supreme Court allowed Oklahoma City to stop integrating its schools, which made it much more difficult for black students to attend majority white schools in the region. The decision also kicked off a period in which schools that had integrated city and suburban districts separated them once again.

Nationwide, in 1954, zero percent of black students attended majority-white schools. By 1972, that number was 36.4 percent, according to Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future, a report by Orfield and Frankenberg. School integration reached its peak in 1988, when 43.5 percent of black students attended majority-white schools, but that number has declined since then, and in 2011, stood at just 23.2 percent.

Charlotte, North Carolina, and surrounding Mecklenburg County had been a leader in school-desegregation efforts, but in 1997, a parent challenged the integration plan in court. In 2002, Charlotte implemented a race-neutral plan and, as a result, re-segregation has occurred, with schools in wealthier areas being mostly devoid of black students, most of whom are low-income. In 2002, the typical black student was in a school that was 35 percent white; today the typical black student in Charlotte is in a school that is less than 20 percent white. A recent paper showed that the end of race-based busing in Charlotte led to increases in crime for minority males, and decreases in high-school graduation and four-year college attendance for white students.

San Francisco and Denver also ended the use of race-conscious policies to determine school assignment, and saw a “substantial increase” in school segregation, according to a brief filed by 553 social scientists in support of Jefferson County in the Supreme Court case.

“We live in a complex multiracial society with woefully inadequate knowledge and little support for constructive policies geared toward equalizing opportunity, raising achievement and high school completion rates for all groups, and helping students learn how to live and work successfully in a society composed of multiple minorities,” Orfield and Frankenberg write in their report.

Yet Louisville and Jefferson County are still fighting to maintain their integration, even though the district is located in a “red” state, which tried to pass bills ending the school busing in 2011 and 2012. In the Brown at 60 report, Orfield and Frankenberg note that Kentucky, West Virginia, and Iowa were the most integrated states for black students in 2011-2012. California, Texas and New York were the most segregated states for black students in the same year.

“We have a lot of students in high poverty, a lot of students who come to us with a lot of issues because of that poverty, but we need to be the equalizer at giving those kids a shot,” Helene Kramer, the school spokeswoman, told me. “As a matter of fact, some of the highest-achieving schools in the district are the most diverse, because they’re good and everybody wants to go there.”

It’s a vastly different attitude than the one found in many other regions around the country, especially Detroit, where L. Brooks Patterson—the head of Oakland County, the wealthy region north of the city—bashed the city in a wide-ranging New Yorker interview. He also said he had no interest in any collaboration between Detroit and Oakland County, even when it came to the water system. “But the debt—why would I want to pick up a share of that? I had no responsibility for creating it,” Patterson told the New Yorker reporter, Paige Williams. “They’re not gonna talk me into being the good guy. ‘Pick up your share?’ Ha, ha.”

The integration plan in Jefferson County and Louisville might not be perfect, but the very fact that the region is still trying to work together and provide equal opportunity to all of its students makes it stand out, said Gary Orfield, of the Civil Rights Project. When most other regions have given up, or fought integration plans with every resource, Louisville has continued to strive for diversity. In 2012, for example, half of the 14 candidates running for Jefferson County School Board ran on a platform of replacing the school-assignment policy with one that would have let students attend their neighborhood schools. All seven candidates were defeated at the polls.

That conscious commitment to diversity indicates that Louisville is still thinking about how to try and make things fair, Orfield said.

“School integration was never meant to be the only solution, but it is it is an essential and necessary element, they’ve at least kept that going, in spite of all kinds of problems over the years,” Orfield said. “They believe it works, not perfectly but a lot better than the alternatives.” It’s possible that commitment to diversity is a result of the integration that was forced on the region, in the 1970s. Now, people who grew up in integrated schools want the same for their children.

While in Louisville, I visited the predominantly black West End, one of the poorer areas of the city. I ran into Bill Huston, who lives in the area, and whose daughter is bused out of the area for school. Huston, who had his daughter later in life, said achieving integration is worth the hassle of having his daughter go to school far away.

“I’m old enough to know why there was desegregation in the first place,” he said. “Some people might have forgotten the reason behind it.”

Jessica Goldstein, the Louisville resident who was bused to a West End middle school during her own childhood, moved back to the area just recently after living in San Francisco and Ann Arbor. When she and her husband were looking at houses in Louisville, some friends told them they needed to live in Oldham County, or consider private schools, to avoid busing. But she and her husband bought a house in Jefferson County, primarily because they wanted to be able to walk to restaurants and coffee shops.

When it came time to look at schools for her son Simon, though, she toured the nearest elementary school and was surprised at how white it was. Then she toured Brandeis Elementary, a magnet school in Louisville’s West End. She loved the math and science work the kids were doing, and she loved the diversity—there were kids from all over the city, with different religious and ethnic backgrounds. She decided this was the school for him, and her 8-year-old son now goes there happily, despite the school’s distance from his house. Her goals for her son’s schooling were academic excellence and exposure to diversity, she said, and she’s been able to achieve both in Jefferson County.

“The only way to make people comfortable with people from different backgrounds is just to spend more time with them—and some schools in Jefferson County are more successful with that goal than others,” she told me. “I don’t want my son to go to school in a bubble.”