What is going on in South Korea?

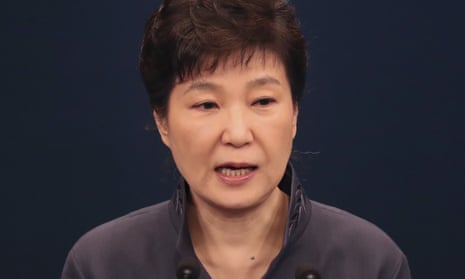

South Korea’s president, Park Geun-hye is confronting the most damaging political crisis of her four-year presidency. At the centre of the growing scandal is Park’s relationship with Choi Soon-sil, a close friend of 40 years who is being investigated on suspicion of exerting undue influence on the 64-year-old president.

Choi, who befriended Park after the president’s father, Park Chung-hee, was assassinated in 1979, has also been accused of using their friendship for personal financial gain. Money scandals involving relatives of South Korean leaders are nothing new, but many are struggling to understand how Park has benefited from bringing Choi, to whom she is not related, into the heart of state affairs, from checking advance copies of speeches to selecting her wardrobe for public appearances.

According to some media reports, Choi also acts as Park’s close spiritual adviser.

Is the president’s job safe?

Yes … for now. South Korean presidents can serve only one five-year term, and it is now unlikely that Park has the political capital she needs to go through with plans to allow the country’s leaders to serve a second term.

With a little over a year left in the presidential Blue House, one likely scenario is that she will be allowed to limp on until a new leader is elected towards the end of 2017.

Despite widespread anger over her conduct – which last week elicited a brief apology that many have criticised as woefully insufficient – Park has not indicated she is ready to resign, and calls for what could be a lengthy and damaging impeachment have so far failed to resonate.

But there is little doubt that Park’s presidency has been irrevocably damaged by revelations about her ties to Choi, who after hiding out in Germany is now in “emergency detention” in Seoul facing questions over alleged influence peddling and fraud.

Who is the woman at the centre of the scandal?

Until recently, the 60-year-old Choi largely operated under the media radar as Park’s adviser and, according to some media, as her spiritual guru. Those revelations alone would not have invited the opprobrium heaped on Choi and Park had it not been for Choi’s apparent influence on economic, foreign and defence policy – and allegations she used her position to pocket some of the $70m she solicited from major South Korean companies for two foundations she had set up.

Choi was first seen in public with Park in the late ’70s after the assassinations of the latter’s father. Park has described Choi as a source of comfort during difficult times in her life, but denies granting her the sort of influence that would be unprecedented for a private citizen who has never held public office and does not have security clearance.

Choi is the daughter of Choi Tae-min, a self-styled Christian pastor who founded a religious cult called the Church of Eternal Life that is now led by his daughter. The older Choi, who died in 1994, befriended Park after her mother’s death at the hands of a pro-North Korean spy in 1974. He reportedly told the young, grieving Park that her mother had appeared to him in a dream and asked him for help.

What has the public reaction been?

The response from South Korean voters has been brutal. Thousand of protesters took to the streets of Seoul and other cities at the weekend to demand her resignation. Having exploited her father’s role in developing the South Korean economy – and deflecting criticism of his human rights abuses – Park came to power promising better ties with North Korea and progress for the country’s economy. Four years later, she has failed to deliver on both policy commitments, leaving her with little political room for manoeuvre as she attempts to contain the scandal. Park’s approval ratings have plummeted to about 10% – by far the worst since her inauguration in February 2013.

Where could this go?

Park has attempted to defuse the crisis with a root-and-branch reorganisation of her embattled administration. Last week she told 10 of her senior secretaries to resign; on Wednesday, she moved again to divert attention from the scandal by appointing a new prime minister and finance minister.

The measures failed to have much impact, however, with opposition parties accusing her of shuffling senior staff in a desperate attempt to save her presidency. It isn’t clear how much influence the new prime minister, Kim Byong-joon, will have over policy. The Chosun Ilbo, South Korea’s biggest newspaper, last week urged Park to appoint a caretaker premier and in effect end her involvement in governing the country.

Does it have implications outside South Korea?

Early coverage of the scandal was mostly confined to the domestic media, but the lurid details of Choi’s relationship with Park have caught the attention of the international media in recent days.

The scandal has caused only minor ripples on the stock and currency markets, but it he will be causing concern in the US and Japan as they seek to put on a united front over North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme.

Amid such low expectations for the rest of Park’s term, it would probably take a dramatic development in inter-Korean relations to gauge just how much Choi-gate has compromised her ability to govern. If Park does survive until the next election, the UN general secretary, Ban Ki-moon, is among those being tipped to succeed her.