It’s time to have a talk about “The Talk.”

For generations, black parents have given the same lecture to their children: Don’t act out. Stay away from bad places. Avoid confrontations.

It’s a how-to guide for surviving police encounters, a list of do’s and don’ts every black person should follow if they want to avoid being brutalized or killed by police officers or other white people.

But after the deadly confrontations we’ve seen in recent weeks, what exactly should black parents be telling their kids now?

Don’t resist police. That advice didn’t appear to help George Floyd, the black man in Minneapolis who died this week after a white police officer put his knee on Floyd’s neck while arresting him. Floyd had called out for his mother while gasping, “I can’t breathe.” Surveillance camera footage does not appear to support the police’s assertion that Floyd resisted arrest.

Stay away from bad places. That didn’t seem to work for Breonna Taylor. She was an EMT who was shot at least eight times and killed after police officers forced their way into her Louisville, Kentucky, apartment in March while she was sleeping. Police say they were there to serve a search warrant for a narcotics investigation and exchanged fire with Taylor’s boyfriend. No drugs were found in the home.

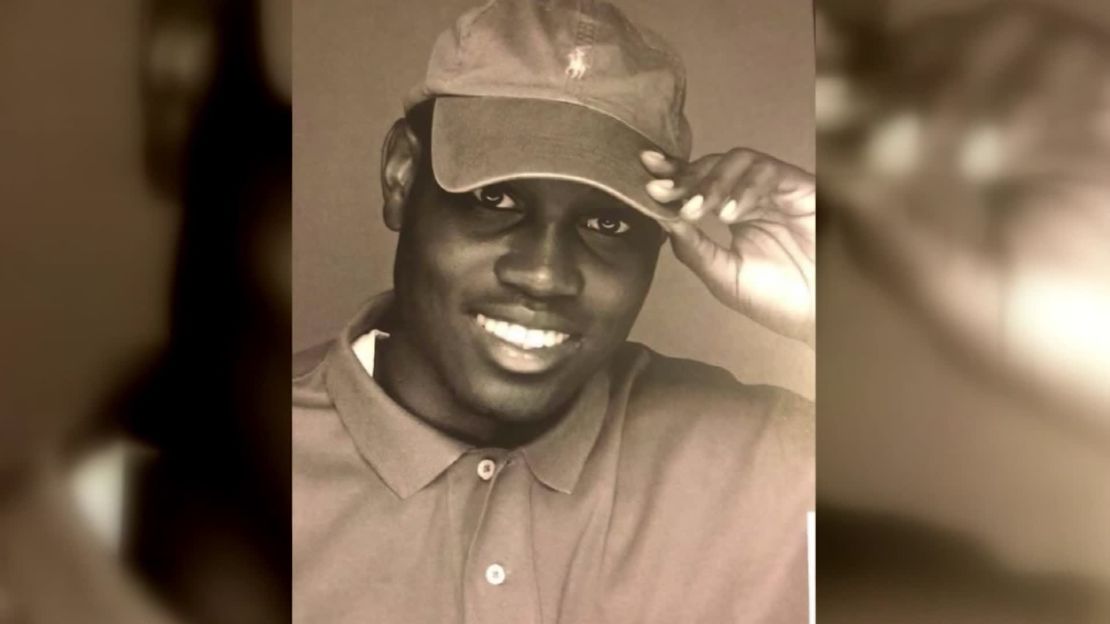

Avoid confrontations with white men. That didn’t save Ahmaud Arbery, the 25-year-old unarmed black man who was fatally shot while taking a jog in rural Georgia in February. Arbery was followed by two armed white men in a truck who later said he looked like a suspect in a string of local burglaries.

Be respectful when you talk to white folks. That didn’t seem to help Christian Cooper, the Ivy League-educated black man who was bird-watching in New York’s Central Park last weekend when a white woman threatened to call police on him after he confronted her about not leashing her dog. In video Cooper shot that shows part of their encounter, he seems calm and polite.

Some black people may now be wondering if there is any precaution they can take that will protect them during encounters with white people.

Read more from John Blake:

“It is impossible to be unarmed when my blackness is the weapon you fear,” the Rev. Traci Blackmon concluded after seeing repeated incidents of unarmed and nonviolent black people being struck down by police.

Blackmon, a pastor and activist in St. Louis, made that statement four years ago. One could argue that the guidelines in The Talk offer even less protection today.

‘The Talk’ is mostly about how to behave around police

This version of The Talk is a holdover from the days when a black man could be lynched for “reckless eyeballing” and “bumptious contact,” or for simply refusing to step off the sidewalk when a white person approached.

Watching the Floyd video brought back some painful memories for Fred Robinson, a minister and father of three children, including one teenager. Robinson says he, too, was taught to cooperate with cops. He recalls how his father reacted one day when police officers detained his older stepbrother and brought him to the house.

“My father slapped him down, and the police said to him ‘you can handle him now,’ ” says Robinson, who lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. “It was typical. We whip our kids so the police won’t have to.”

Robinson says he teaches his children how to “de-escalate” situations with the police, but he wonders what behavior even works anymore.

“You used to say do what the police tell you and you’d probably be alright,” Robinson says. “You don’t get that sense anymore.”

But maybe it’s time to shift its focus

The Talk has to change, says Robinson, who adds that it traditionally put the burden on black behavior. There wasn’t a critique of police behavior – It was all about what black people were supposed to do.

That created a sense of hopelessness, he says.

“It puts the focus on us rather than where it should be – on racism in the police department and the way black people are targeted,” he says. “We are Americans and we ought to have a right to have a bad day, to question a police officer or to question an order that doesn’t seem right.”

In the meantime, Robinson says he and his wife continue to have The Talk with their 27-year-old son and their two daughters, ages 22 and 19.

He says he teaches his children how to be aware of their surroundings and a police officer’s movements and how to calm a situation. He also teaches them they have a right to question the police – but only in a way that doesn’t endanger their lives.

“We have to be better trained than the officers, and that’s a damn shame,” he says.

Robinson says he also tells his children they have a right to be angry. He himself got angry when he watched the video of the white officer who knelt on Floyd’s neck as he held him down.

“He knew he was being filmed and he still responded as if he knew his whiteness was inevitably going to protect him,” Robinson says. “That kind of arrogance – what can you do?”

More black parents may be coming to a conclusion that’s as stark as the videos of these tragic incidents: Do everything right and it may not matter.

The talk may no longer protect us.