As she lay on the floor, just metres from the remains of a suicide bomber who had ripped apart her metro train, Samla da Rosa’s first instinct was to reach for human contact.

“We hugged each other. I hugged this young guy in front of me, and I was asking him, ‘Why? Why are they doing this?’” It was a question that would echo around the city for days.

Less than an hour earlier, when the day’s first two bombs devastated Brussels airport, Da Rosa called to check up on her husband. “I told him I am fine. I am having my breakfast and preparing to go to town on the metro, so don’t worry. Everything is fine.”

She had ended up just one carriage away from another bomber, in a charred wreck where she would later hear that 20 people had died. To escape, when she and other survivors decided to risk getting up from the floor, they had to walk through scenes of hell. The explosion had burned away the skin and hair of those closest, and some people had lost all sense of where they were. “Other wounded people were like zombies, walking without direction,” she said, and body parts lay on the floor.

But when Da Rosa marked her birthday on Thursday, the only people she wanted to be with were the unknown men and women who had lived through the carnage, not her husband or friends she had got to know over 19 years in Belgium.

“I turned 54. I spent the whole day trying to find someone who was there with me,” she said, recalling a strange sense of closeness born of horror. “They say that you are born alone and you will die alone, but when you have an accident like that, I didn’t feel alone because the solidarity was so big.”

That sense of mutual aid was the opposite of what the men who tried to kill her wanted – to sow hatred and fear through death. They killed 31 people and injured 340 in blasts so devastating that many of the dead may not be formally identified for weeks.

Police were on the trail of the suspected bombers soon after they put out security camera footage of the men, pushing luggage trolleys through the airport. They were marked as suspicious partly because they were wearing gloves on only one hand, thought to have concealed their detonators.

A taxi driver called a tipoff line after he recognised a group of difficult clients from that morning, unusually edgy about handling their large suitcases. The unnamed driver may have averted an even greater tragedy, when he refused to take one piece of baggage because the car was overloaded.

A raid on the address he gave in the Schaerbeek district turned up 15kg of explosives, detonators and a suitcase filled with nails and screws, along with vital clues to the identity of at least two bombers – formally named the next day as petty criminals Ibrahim (known as Brahim) el-Bakraoui and his brother Khalid.

Other raids in the same street turned up a computer tossed in a rubbish bin with a confused statement from Ibrahim, one of the men who killed themselves at the airport. He described feeling “in a rush, not knowing what to do, being hunted everywhere, not being safe, and if this goes on, ending up in a cell”.

The desperate hunt for the bombers and their associates has exposed not just the men behind the bloodshed, but a string of basic, and tragic, intelligence failures that have led some to question whether Tuesday’s bloodshed could have been avoided.

Grim details of missed clues and ignored intelligence trickled out as authorities chased associates of the men across France, Belgium and Germany. By Thursday, the justice and interior ministers had both offered their resignations, although the prime minister refused to accept them, on the grounds that the country needed continuity in crisis.

The most dramatic revelation had come from President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey, who revealed the day after the attacks that airport bomber Brahim was expelled from the country in July after being seized near the Syrian border. Turkish authorities explicitly warned Belgian and Dutch counterparts of suspicions that he was a militant, but that alert never got through from Belgian diplomats to security forces at home. Nor had authorities chased down Bakraoui for skipping parole after serving less than half his nine-year sentence for armed robbery. A parliamentary inquiry will look at the mistakes.

“You can ask how it came about that someone was let out so early and that we missed the chance to seize him when he was in Turkey. I understand the questions,” said interior minister Jan Jambon.

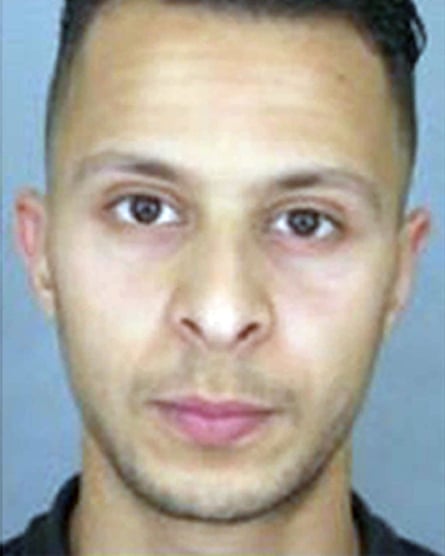

The week had appeared to begin well for security forces, who had just captured the Paris attacker Salah Abdeslam, after four months on the run. But the man they thought was the last surviving member of a broken terrorist cell turned out to be part of a more sophisticated international network of attackers that was still active.

Even the French president has been circumspect about how fast intelligence teams can trace and dismantle a system forged in Syria and Iraq, and bolstered by ties of family and childhood friendship at home, apparently tied to a string of terror attacks from the Charlie Hebdo shootings to the Brussels bombs.

The two Bakraoui brothers, both Belgian nationals, had long criminal records but officials had not detected any links with terrorism. It has emerged that they had connections to the Paris terror cell, as did a second airport bomber. DNA linked Najim Laachraoui to two of the explosive belts used in the Bataclan concert hall.

So a key question now hanging over this week’s tragedy is whether it will prove the bloody but final unravelling of the main Isis operation in Europe, or whether authorities are simply chasing another disrupted cell in a larger and more durable operation.

“We don’t have to be proud about what happened,” Koen Geens, Belgium’s justice minister, said of the government’s failures to halt the attacks. “We perhaps did things we should not have done.”

After Turkey’s dramatic revelation, a local police force admitted that the key to finding Europe’s most wanted man lay unread for months in the filing cabinet of a Belgian police station. A beat officer had worked out that a relative of Abdeslam was living at 79 Rue des Quatre Vents, and was thought to have been radicalised. Three months later, with the report still unread, police finally descended on the apartment and found Abdeslam inside.

His relative, Abid Aberkan, had served as coffin bearer for Salah’s brother and fellow Paris attacker Brahim just the day before the raid. If Abdeslam had been seized earlier, police might have found links to other members of a network apparently centred on a group of former petty criminals from Molenbeek.

The rundown neighbourhood near the heart of the city was also the childhood home of suspected cell leader and mastermind Abdelhamid Abaaoud, and another man now being urgently sought by police in connection with the attacks, Mohamed Abrini.

Twin ties of blood or friendship and extremism was a pattern repeated again by the Bakraoui brothers, and apparently key to the operation of a vast and brutally ambitious network of militants under the noses of an intensive European police operation.

“All the individuals are linked one way or another to each other. Either they have met in Syria or Iraq, or they are connecting up with friends in Brussels. This is the modus operandi that we’ve seen at work since November, but it could even go further back, perhaps since the Charlie Hebdo attacks,” said Professor Rik Coolsaet, of the Ghent Institute for International Studies, an expert on radicalisation.

“Foreign fighters who return are linking up with local sympathisers who have never been to Syria but who they know from their youth, school, sports club so on. So you have guys coming over with expertise in assault weapons and explosives and local friends and kin who do the logistics.”

Many of the men behind the Paris and Brussels attacks are now dead or in custody. European police have rounded up around 20 people in recent weeks, across France, Germany and Brussels. More than a dozen have died as suicide bombers or in standoffs with police.

But Abaaoud, the man thought to be a key planner for the group behind the Paris attacks, boasted to a niece that he had brought around 90 militants back to Europe with him.

The French president, François Hollande, apparently warned of a much wider, deep-rooted web of terrorists on Friday, when he said that while one cell was being wiped out, there was still a serious threat. “We know that there are other networks,” he told journalists. For police trying to ward off future attacks, that is a frightening challenge, because of both the scale of the exodus of young radicals to Iraq and Syria since 2012, and the pace of returns in recent years.

“All the indications are that apart from this network or cell, which probably has been dismantled, there are probably others still running around in different European countries,” said Coolsaet. “For example, the man arrested yesterday in France appears to have been part of a parallel network operating in the Francophone sphere.”

In Belgium alone, there are thought to be at least 130 returnees, he said. It is very difficult for authorities to distinguish those who left the Isis frontline because they were disillusioned by violence, from those who found it inspiration for further atrocities at home.

A third of those who made it back to Belgium have already been jailed, but there is no way authorities can monitor all the others around the clock, given that a 24-hour surveillance operation on one person requires 30 to 40 officers. The close-knit network of family and friends that produced so many of the attackers then sheltered Abdeslam after the atrocities in Paris has made the work of police officers particularly hard. Brothers who call each other regularly are less obviously suspicious than acquaintances who suddenly start having more frequent contacts, so networks built around old friends and relatives can keep a lower profile, and are harder to infiltrate.

They have also put communities under a painful spotlight, which often ignores those claimed by extremism, such as 30-year-old Loubna Lafquiri. A well-regarded local gym teacher and mother of three, the Molenbeek resident was one of the first victims of the Maelbeek blast to be named.

“For those who still doubt it, we were also among the victims of these sects,” says Jamal Ikazban, the local MP and a former social worker in Molenbeek. Community leaders and activists say they are trying to root out extremism.

As another would-be bomber was captured at a city tram station, a local imam, Jamal Zari, told his congregation in a Friday sermon: “Nothing can explain or justify protecting people who are dangerous to society. There is no alibi. Even if it’s your father, your son, your daughter, there is no question. You cannot protect those people. Our faith forbids it.”

But experts warn that Belgium must also tackle problems of racism and alienation that make young Muslims vulnerable. In districts such as Molenbeek, as many as one in three young people cannot find work, and each time there is another attack, the risk is that it will exacerbate divisions.

“With every plot, the same is always true, the biggest danger is one we are creating ourselves – the polarisation of society and deepening of animosity against migrant communities,” said Coolsaet. “Eighty per cent of those who left Brussels [to fight in Iraq and Syria] are children or grandchildren of Moroccan immigrants. The fact that even after three generations we are still calling them Moroccans is something they feel very strongly and creates a gap that can be exploited by extremists.”