Editorial: No Child Left Behind: how to end ‘teaching to the test’

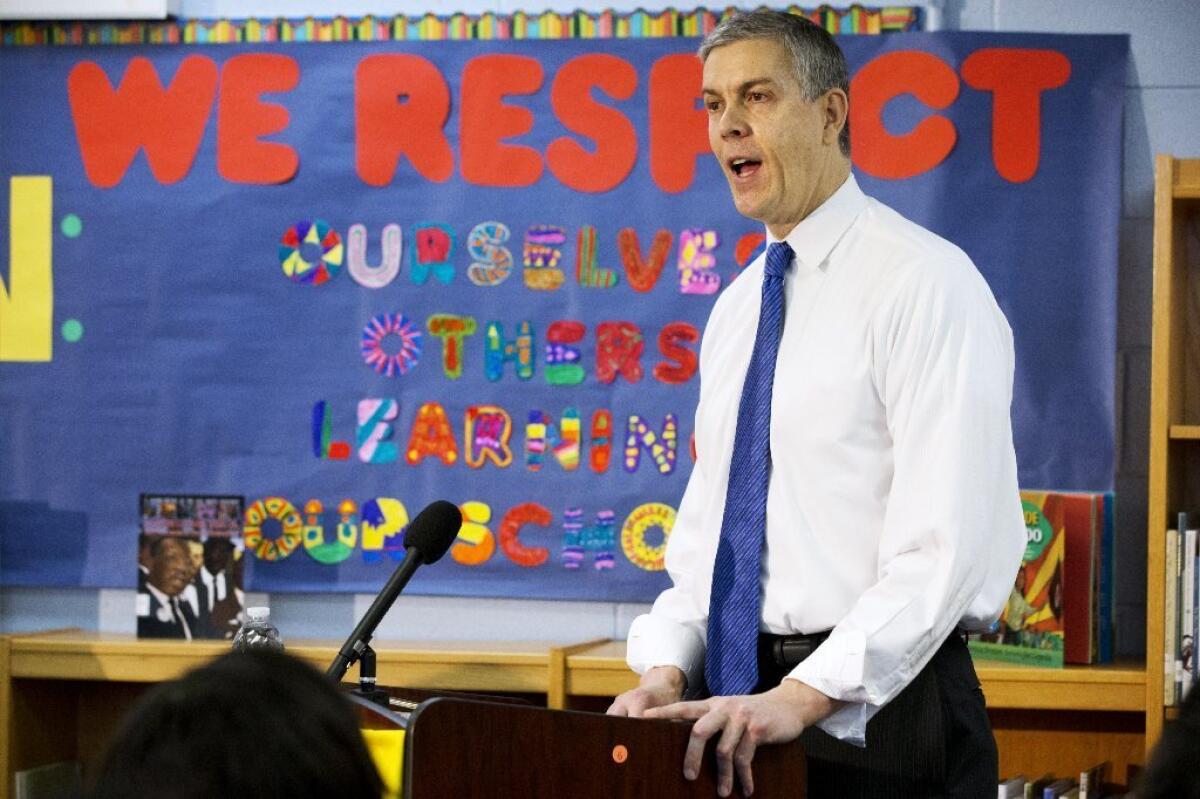

When U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan said last year that the incessant focus on testing was “sucking the oxygen” out of public school classrooms, his statement seemed like a pointed criticism of the federal No Child Left Behind Act and of his own long-standing policies. For the last 14 years, the law has pressured public schools to raise scores in math and reading; that in turn has led schools to “teach to the test” — and to administer increasing numbers of interim tests throughout the year, as schools and individual teachers have tried to determine whether students are on track to score well on the all-important year-end exams.

But it turned out that Duncan wasn’t saying what critics of No Child Left Behind had hoped: that there should be fewer standardized tests, which are taken annually in grades three through eight and once in high school. Instead, Duncan proposed giving states incentives to get rid of other “redundant and low-quality” exams. The problem is that as long as there are annual high-stakes tests, schools are going to prepare for them with their own tests.

Duncan is right when he says the annual tests provide important information about schools. They should remain a component of the law, along with high standards for what students should learn. The better way to ensure that test prep doesn’t replace

creative, stimulating lessons in class is to relax the law’s rigid reliance on scores as a measure of school and teacher performance, and to tone down its harshly punitive elements.

For one thing, the Obama administration should drop its insistence that the test scores be used as a major measure in teacher evaluations. That is now the rule in the 43 states — California isn’t one of them — that received waivers from No Child Left Behind, and the administration clearly wants to make it a requirement for all states if the law is reauthorized this year. But the value of this approach has not yet been proved, and as long as states show academic progress, the federal government shouldn’t interfere in how they go about it.

Ref Rodriguez, a candidate for the Los Angeles Unified school board and operator of several high-performing charter schools, says he doesn’t find the year-end exams a useful tool for evaluating teachers. Instead, he says, his schools use interim tests designed by the teachers themselves. This page has argued that standardized test scores can play a small but useful role in teacher evaluations, but they do not have to be as significant a component of the evaluations as the federal government wants them to be.

Although schools’ annual test scores should be reported publicly, it might not be necessary for all of them to count as a measure of whether the school has improved. If high schools can be judged by only one year of testing, why not allow just one grade of middle school and one or two of elementary school to count as markers of achievement? That would relieve some of the incessant testing pressure. Now that more students are being prepared for college, the SAT or ACT might be able to replace the existing high school test, reducing the number of exams for which students and teachers must prepare.

A revised No Child Left Behind law also should broaden the definition of academic progress, just as California is doing with the redesign of its Academic Performance Index ratings. Instead of just measuring how students are doing on the standardized tests, the federal government could also judge schools based on graduation rates, regular school attendance, portfolio and project work, parent satisfaction and enrollment in college-prep and advanced courses. In addition, the consequences for not performing well should be more about intervening to help schools improve, not about punishing them.

The political winds are blowing against the Obama administration: Parents as well as teachers are frustrated, states have been postponing or withdrawing from the Common Core curriculum initiative, and in Congress, the GOP appears bent on making No Child Left Behind completely toothless. But there’s a better reason for the administration to revamp its thinking on tests: creating a more robust and engaging educational system.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.